I wish I could say that in a trip that covered something like 6,000 miles over 23 days that we met lots of people and had deep conversations that led to profound personal discovery. We didn’t. And maybe the stats mentioned in that first sentence explain part of the reason. We were actually actively traveling for just 15 or 16 days, which means we were covering 400 miles a day on average. That’s nothing for The Great American Road Warrior, for whom 500 or 600 or even 1,000 miles a day is routine (I once took a trip back to Chicago from Berkeley with my son Eamon that covered 2,100 miles in all of 40 hours, even with an overnight stop in Cheyenne, Wyoming). The point being: Even at 400 miles a day, the modern traveler isn’t going to spend a lot of time in intimate conversation with random acquaintances on the road. Even if you’re the kind of person who easily strikes up a conversation with a total stranger, which mostly I am not.

On the other hand, the conversations that do happen tend to stand out.

When John and I stopped at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana, one of the main destinations on our trip, we encountered a group at the top of what has long been known as Last Stand Hill, the place where Lt. Col. George A. Custer and the remnants of his command died together on June 25, 1876. People were listening to a ranger named Michael Hasch recount the progress of the battle. I was impressed by Hasch’s command of the lore surrounding the battle, including the many first-person accounts from Native American participants. One moment I remember in particular from his talk: The moment when a Cheyenne named Lame White Man rallied fellow warriors to the attack by shouting, “Come! We can kill them all!” Hasch has a deep voice, and it carries. He spoke slowly, deliberately, and when he intoned those words, it was like the moment was coming alive again. After his presentation, I talked to Hasch and discovered he is a former Pittsburgh newspaper reporter who began volunteering at the battlefield a decade ago. One of the people listening to that conversation was a woman who used to be a local news anchor in San Francisco, and that led to yet another conversation with a stranger. But that’s another story.

So, that’s one encounter during our trip across the country. Here are a couple of others:

We met Laura and Jamie at the top of Teton Pass, Wyoming (elevation 8,432 feet above sea level). We had driven up the west side on our way from Idaho to the Grand Tetons and Yellowstone. They arrived pushing a heavily-laden tandem bike up the east side.

What was their story? They said they had both quit their jobs, sold their home and most of their belongings and had a custom tandem built. Their plan was (presumably still is) to spend five years cycling around, mostly in Europe. They had ridden from Connecticut by way of Louisiana to get to this spot on Wyoming Highway 22, and planned to cycle up the west flank of the Tetons before heading east into Yellowstone. After that, they’d make their way east and south to Florida, where they planned to spend the winter before heading to Europe. The biggest impression they made on me was how cheerful they were after pushing their machine up the last two miles of busy roadway up to the pass. I, too, have pushed my bike up steep mountain roads, and I’m not sure I was smiling all the way.

What more can I say about these two? Godspeed, Laura and Jamie.

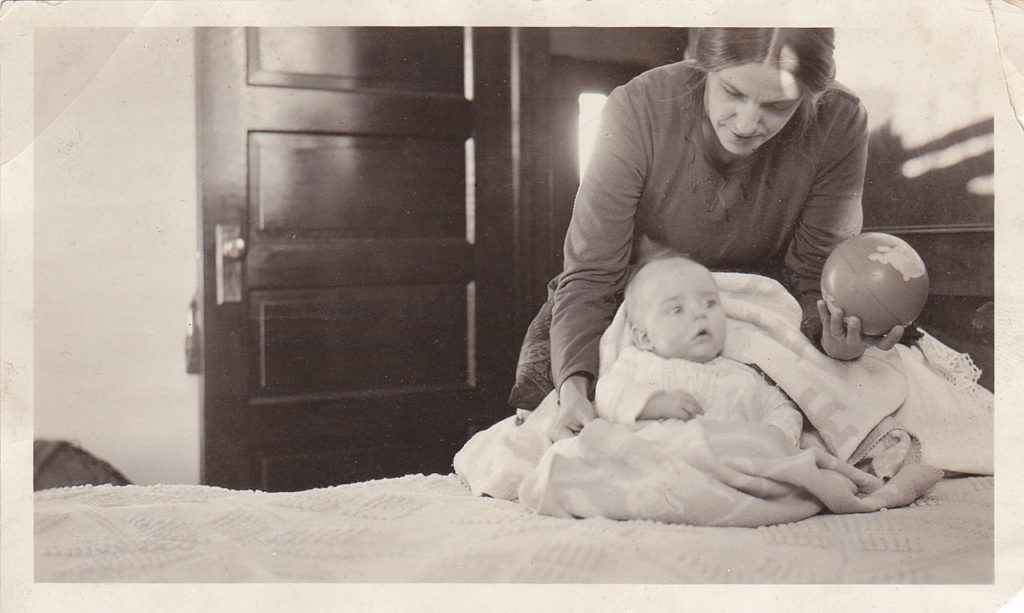

The motive for our road trip (or excuse, maybe) was to commemorate what would have been our dad’s 100th birthday in early September by visiting his birthplace and first hometown in northwestern Minnesota. We got to Marshall County a few days after the actual centennial, and spent much of the day taking pictures at a rural Lutheran church where our grandfather, Sjur Brekke, was pastor a century ago. The we headed to Alvarado, population 300, where Sjur, our grandmother, Otilia, and dad lived (and where Sjur saw to another Lutheran congregation). After that, we drove the five or six miles east on Minnesota Highway 1 to Warren, the county seat, where Dad was actually born. One thing I had discovered about Warren during a 2018 trip through the area (and somehow had missed during a couple of much earlier visits) is that the town’s drive-in theater, the Sky-Vu, is still in business.

John and I pulled in to the Sky-Vu to take a look. Like everyplace else where we stopped for more than a couple of minutes, we brought out cameras and started strolling around taking pictures. Next door, a man on a riding mower was cutting the grass on a sprawling lawn in front of a big ranch-style house painted the same pink color as the concession stand/projection booth at the theater. After about five minutes, he drove the mower over to see what we were up to.

“Your place?” I said. Or something like that. And it was. His name: Leonard Novak, and he said he’d bought the Sky-Vu in the early 1970s and that he and his family have been running it since; a grandson is doing most of the work now. As it happens, KFAI in Minneapolis did a nice radio documentary about 10 years ago featuring the Novaks and the Sky-Vu in which Leonard says he doesn’t foresee the theater closing, ever: “We’re the only one (drive-in) between Winnipeg and Minneapolis.” And judging from the fact it’s still open, and still showing first-run movies, maybe he’s right.