Back in Berkeley now — since late, late Monday night; remind me to bore you with the tale of United Airline’s feat of taking half an hour to move a planeload of bags 100 yards — but I undertook another family cemetery excursion in Chicago before returning west. And another cross-city bike ride, too.

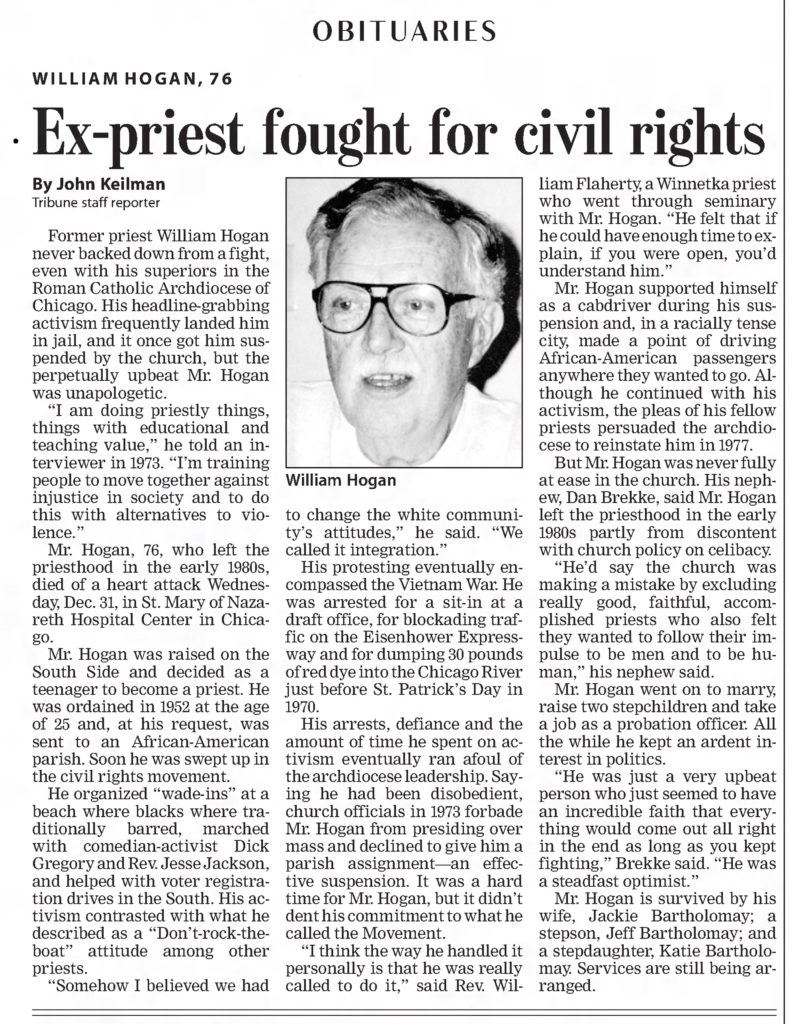

I decided to go out to Mount Olive Cemetery, where my dad’s parents and other relatives are buried. I’ve only been there once: for my grandmother’s funeral, thirty-one years ago this month. Otilia Sieversen Brekke was buried next to my dad’s dad, who died twenty-two years to the day before I was born. I’d never seen his grave before: Sjur Brekke. 1876-1932. He was a Lutheran minister and member of the Hauge Synod, a branch that rebelled against the state-established Lutheran church in the early 19th century (bits of the history here and here). He died when Dad was just 10, of Parkinson’s Disease, long before there was an effective way to treat it.

I rode from Dad’s place, roughly Touhy and Western (7200 North, 2400 West) to the cemetery, near Narragansett and Addison (3600 North, 6600 West). I did an online map of the route I took, but the rough path was: Pratt west to Kedzie; Kedzie south to Irving Park; Irving west to Pulaski; Pulaski south to Addison, and Addison to Narragansett; on the return: Narragansett north to Nagle; continuing north on Nagle to Gunnison; west on Gunnison to Austin; Austin north (with the help of a pedestrian overpass across the Kennedy Expressway) to Bryn Mawr; Bryn Mawr east to Elston; Elston north to Central; Central north to Devon; then winding through side streets east and south back to Bryn Mawr (there’s a river and expressways and forest preserves in the way of a direct route); Bryn Mawr east to California, and California north to my starting point.

Aside from that numbing recitation of street names only a Chicagoan could cotton to, I have to observe that while I had to ride on busy streets with plenty of traffic, the local drivers behaved pretty generously to the freak on a bicycle they encountered. I’m sure riding day in and day out you get to see the same hostile attitude on occasion that’s a daily reality riding in California, but on my two long city rides, I had just one car honk at me, heard no one curse me for being on the road, and saw no raised digits.

When I got to the cemetery, I rode in the gate believing I’d be able to hunt down Sjur and Otilia’s headstone from my thirty-one-year-old memory. I rode in a couple hundred yards and when I came to a turn realized how much I’d overestimated my power of recall. Before I turned back to the cemetery office, I saw a sign listing prohibited cemetery activities. Bicycling was one. I rode back to the gate, went into the office, and asked the manager for help finding the Brekke site, mentioning that I hadn’t been to the cemetery since 1975. He complied with no hint of enthusiasm or engagement, but didn’t say anything about not cycling in the graveyard. He gave me a very general outline map of the grounds and marked the rough location of the grave in Section G, Lot 482. The guidance was good enough, though: I found the spot after looking for no more than 10 minutes. Different from how I remembered it.

When we were down at Holy Sepulchre on Sunday to see my mom’s family burial places, Dad commented on how much more activity there was there than at Mount Olive. Tuesday afternoon, I saw just one car in the cemetery. The place has a bit of an about-to-be-overgrown feel to it. The ground seems unlevel. Stones are leaning and atilt, and rows don’t seem to line up. The grass is a little long. It’s not a bad feeling, in itself; the trees out there are beautiful. It’s just that the families that buried parents, spouses, siblings, and children here have gone somewhere else — California, for instance. They don’t come back often or at all, and nobody’s minding Uncle Ole’s little patch up there on the Northwest Side too closely anymore.

A friend of mine recently called cemeteries a waste of valuable property, and I know what he was saying. It’s a lavish use of land. Out of necessity, mostly, other cultures seem to remember the dead a bit more economically; in Japan or China or India, where land is food, it would be reckless to give so much to those who no longer need it. The thought came to me while I was out amidst the Brekkes and Reques and Sieversens (all my dad’s folks) that cemeteries are memory; that’s what gives them value, that’s what makes them poignant and absorbing even when you know nothing about the people you encounter there. Our national fascination with genealogy aside, though, memory — the kind that tries to weigh the past, personal and collective, not to romanticize it but to provide context and maybe a lesson or two for the present and future — doesn’t look like a hot commodity. People without that sense of memory, of the value of memory, of the importance of connecting today with what’s gone before and what’s to come — for them, cemeteries might really be a waste.