While recently pursuing Irresistibly Absorbing Research on the origins of Oakland’s King’s Daughters Home, I happened across a resource that is itself irresistible and absorbing: The Library of Congress’s Chronicling America collection of historic U.S. newspapers. It’s an archive of selected papers published between 1836 and 1922. In doing a quick trace of the history of the King’s Daughters establishment, several stories from the old San Francisco Call, part of the Chronicling America collection, helped fill in blanks.

I went back the next day to see what else might be there. Since I’ve been doing some genealogical research, I thought I’d look at what Minnesota papers might be in the archive. My grandparents lived in several different towns up there in the 1910s and ’20s, and my dad was born in a little town in Marshall County called Alvarado. It so happens that Marshall County still has a weekly paper published in the county seat–the Warren Sheaf. The Sheaf turned out to be one of the papers digitized and included in the Chronicling America archive. I looked for the issue published the week my dad was born, in September 1921, and came across the following in the “Alvarado News” column:

“Born to Rev. and Mrs. S. J. Brekke last Saturday at the Warren City Hospital, a bright baby boy. Congratulations.”

Going through the Sheaf turned up lots of mentions of my grandfather, Sjur Brekke, who was a Lutheran minister and pastor for several Norwegian congregations in the area: in Alvarado (a town of only a few hundred which at the time had a separate Swedish Lutheran congregation with its own minister), in Viking, at a rural church called Kongsvinger, and apparently in at least one other town. Any time something was doing at the churches, the Reverend Brekke got a mention. Every once in a while, my grandmother, Otilia Sieversen, would make print, too–usually when entertaining guests or when off visiting in one of the neighboring towns in Marshall County.

I cast my search net wide, and looked for any mentions of “Brekke” in Minnesota papers in the archive; my grandfather had a brother, Johannes, who lived with his family in the Fergus Falls area around 1920. Johannes was a traveling Lutheran preacher, so I was thinking maybe I’d come across some mention of him. But I didn’t, and since Brekke is not an uncommon name in Minnesota, I got quite a few hits of folks who don’t seem to belong in the family annals. The most remarkable of these involved someone named Lewis Olson Brekke.

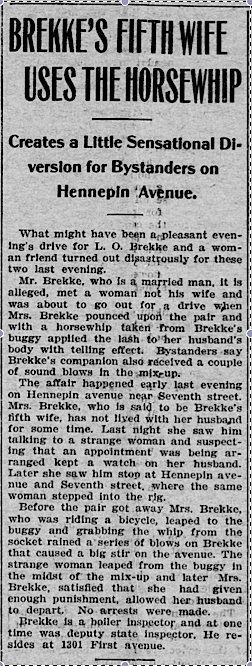

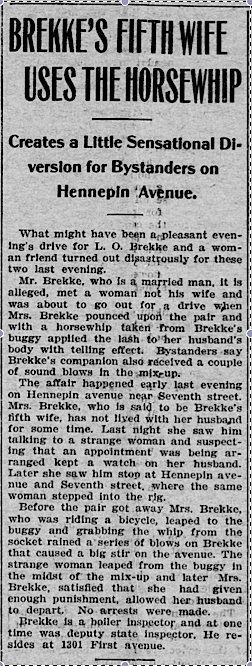

I made his acquaintance in the pages of the St. Paul Globe of Friday, July 10, 1903, under this headline:

Brekke’s Fifth Wife

Uses the Horsewhip

The story, at right above, is a classic police blotter item blown up to separate-item proportions–a marital spat that ends with an ugly scene on a crowded street. The account’s picture of Mrs. Brekke setting upon her cheating spouse with a whip is vivid. But the prize detail for me is, “…Mrs. Brekke, who was riding a bicycle, leaped to the buggy.” She sounds like quite the acrobat.

So that’s that. The unfortunate L.O. Brekke is beaten by his wife, made an object of fun in the local press, and retires to lick his wounds and his pride. Well, no. There’s more to Mr. Brekke’s story. He turns out to have been a sort of running joke for reporters covering the courts in Minneapolis. The year prior to this scuffle, several accounts appeared that detailed a divorce action between Lewis Olson Brekke, the L.O. Brekke of the story above, and his wife, Laura Runbeck Brekke. The Minneapolis Journal reported she had sued for divorce on grounds of “cruel and inhumane treatment” but “could not substantiate her allegations.” Then Lewis sought a divorce on the same grounds, citing his wife’s alleged habit of “throwing various articles of furniture at his head whenever his back is turned.” He said he feared to sleep nights lest Laura attack him, that she called him “vile and indecent names,” and that her ” ‘carryings on’ with a married neighbor had scandalized their acquaintances.” He also claimed he had discovered that she had a common-law husband and thus their marriage was never valid. (In the pages of the Globe, anyway, this way by no means an isolated case. The divorce action featuring the abusive wife appears to have been one of its staples during the turn of the last century. A chance reading of several pages of the Globe finds wives taking swipes at husbands with butcher knives, throwing crockery, wrestling over bicycles, and dumping ice water on their spouse’s heads. And that’s before “Fatal Attraction.” We could have the seeds of a dissertation here.)

It’s not clear how the Brekke divorce suit came out–maybe the stories relating the outcome have not been indexed–but I’m guessing that the “Mrs. Brekke” who resorted to the horsewhip is one and the same as the one who struck fear into her husband’s heart by hurling household objects at him. You’d really like to have a picture of this couple; the best I can do is uncover some of the traces they (and he especially he) left in government documents through the years.

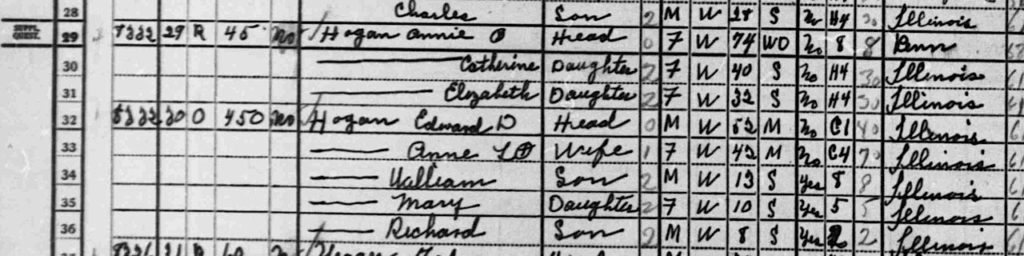

Lewis Olson Brekke, born in Norway, about 1852, emigrated to the United States in the early 1870s, lived in Iowa in the ’70s, in Minnesota in the mid-’80s, then moved to Minneapolis in the early 1890s, and to the Seattle area after 1905 sometime. Lewis was about 50 when accosted by his bike-riding spouse, and Laura Brekke was about 15 years his junior. In the 1900 census, taken in April, she was listed as a servant living in Lewis’s household (the other residents were Lewis’s 13-year-old daughter, whose name was recorded as Ammanda, and three women boarders). Lewis was listed as divorced. Lewis’s and Laura’s relationship bloomed into something else, and they were married in Sepember of that year.

Was she his fifth wife, as the headline says? Maybe. Perusing census and marriage records through FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com–yes, it’s possible to have too many research tools at hand–Lewis shows up in the company of several previous spouses: May (or perhaps Mary) Halvorsen, whom he wed near Decorah, in northwestern Iowa, on December 26, 1874; in an Iowa census taken in 1885, he’s reported as widowed, with three children; later that year, he married a Kari (or Karie or Carrie) Boxengaard in Spring Grove, Minnesota, about 20 miles up the road from Decorah; in September 1893, he married a Phoebe Slocum (she doesn’t sound Scandinavian), in Minneapolis; and then in 1900 we have him tying up with Laura. In later years, he moved to Washington state, and in the 1920 census, nearly 70, he reported himself as married, though no wife was living with him.

As I mentioned before, his divorce and horse-whipping didn’t mark the first time the papers had some fun with him. On Oct. 5, 1892, the St. Paul Globe reported on an apparently fraudulent lawsuit that Lewis had brought against an erstwhile employer:

“The damage case of L.O. Brekke against S.E. Olson & Co. [a Minneapolis “dry goods” store] is over, and the finding of the court is for the defendant. Brekke sued the firm for damages, claiming that while in the firm’s employ he sustained injuries in the store elevator which would render him lame for life. The list of injuries was a long one, as was the number of witnesses who corroborated Brekke’s testimony. The defense introduced evidence from people who lived in Decorah, Io., Brekke’s old home, which proved conclusively that the plaintiff had received the injuries he referred to twenty years ago. He had been lame for the same number of years, and long before he ever dreamed of coming to Minneapolis. Brekke’s divorced wife testified he was lame when she married him long years ago. The case was tried in the United States district court before Judge Nelson.”

A few years later, the Globe dropped in on Lewis as he pursued his duties as deputy state boiler inspector for Hennepin County. He was described as being “considerably incensed” over complaints from residential property owners who felt he was overstepping bounds to “examine every little boiler and toy engine in the city.” Later, he lost out in his bid to be chief boiler inspector for the county, a patronage job.

In various census returns, Lewis listed his occupation as “engineer” or “inventor.” And sure enough, he shows up in the U.S. Patent database for several devices registered over a period of more than 30 years. While he was undergoing his troubles with his soon-to-be horsewhipper, he patented a “folding footboard for iron bedsteads” and apparently started a company to manufacture them. What was the purpose of his innovation? As detailed in the patent application, it sounds like something out of “Seinfeld“:

It is a well known fact that many people object to iron bedsteads simply for the reason that they have no footboard against which the clothes maybe tucked and against which the feet may if desired be pressed. A permanent footboard of the proper dimensions would be objectionable for the reason that the bedclothes could not be thrown over the same in the day time or if so thrown would give to the bed a very awkward and unusual appearance. I believe I have solved the problem in practical and simple manner by providing a footboard which has a folding upper section adapted to be turned flat upon the foot end of the mattress so that the bedclothes may be thrown over the same and the bed given the same made up appearance as if there was no footboard provided. At the same time this folding section may be turned up before a person retires and the bedclothes may then be tucked between the footboard and the mattress. This being done there is nothing objectionable to the bed and the same footboard accommodation is afforded as with an ordinary wooden bedstead.

I don’t find any evidence that Lewis got rich off the revolutionary “swish and swirl” footboard. Or off his other inventions: an improved kerosene lantern, an improved stove and furnace grate, an improved grain-binder, and a draft equalizer (a device to make sure that three-horse teams would plow or pull evenly).

Loose ends I can’t tie up: What happened to those four kids of his? And where did he end up? He had one more turn in court that I can find–testifying in a 1909 death inquest in Washington that he had heard against his drunken landlord threaten to kill his wife shortly before her body was found on nearby railroad tracks. Then there’s the 1920 census, and then nothing–no inventions, no newspaper stories, and apparently no more buggy rides with women friends.

Like this:

Like Loading...