A few years ago, another former teacher of mine, Mort Castle — also a longtime friend of G.E. Smith — helped G.E. pull together the hundreds of poems he had written since he was a boy in central Illinois and select some to be self-published in what turned out to be a pretty hefty volume called “Long Trails from Pleasant Hill.”

At various times, G.E. talked about his youthful ambition to be a writer. Most of the time he was dismissive of his own efforts, though occasionally he would talk about the factors that led him in other directions. For instance, that other writers had already said what he wanted to say, except better (published writers are the ones who realize this and keep going anyway). More significantly: His teaching absorbed so much of his time, intellectual energy and creative attention he didn’t really have the resources to follow his writing seriously. That was not an excuse: He poured all of himself into his classes and students, to the point where the demands he placed on himself brought him to and beyond the point of exhaustion. As Mort remembered in his little introduction to “Long Trails”:

“In 1968, I was Smith’s student teacher. I saw him in action, ‘grading papers,’ and it was not a quick-scrawl ‘Nice figure of speech’ here and ‘comma splice’ there. Not infrequently, a student who handed in a two-page paper received four pages of comment, comment not limited to correcting apostrophe goofs and refining expression, but personal commentary, a Smithian response to what was said and how it was said.”

Still, G.E. had the 800 or so poems, maybe in a picturesque heap that he thought of as organization, probably piled in the post-World War II semi-finished concrete-shell basement of his co-op apartment unit at 134 Dogwood in Park Forest. They probably would have stayed that way except for Mort and a change in G.E.’s own thinking about what his writing represented. “After I left college, I had no interest in publishing my poetry,” he wrote in his book’s preface. “It wasn’t until I began to think, as a genealogist, about how anything written by ancient relatives — even in signature — was (or could have been) so extraordinarily precious that I decided to consider publishing. I realized that I, too, someday, would likely be a long-ago ancient relative to someone who was pursuing my family history.”

So he and Mort brought out the book. I’d like to say that when it arrived here in Berkeley a few years back, I dove into it. But I didn’t. G.E. wrote a long inscription that thanked me, for among other things tracking down a copy of an obscure futurist novel that he had read while sailing from Europe to the Pacific as a Navy Seabee during World War II. I flipped through the book and stopped at a few of the poems. I probably found the project of reading more than a little overwhelming; and I’m sure I also had a tinge of envy and regret that I was holding yet another book by someone I knew while I myself had produced — what, exactly? (If I had ever said anything like that to G.E., he would have had something reassuring to say, then maybe started a conversation about why exactly I thought writing a book was important. Mort would have just said to sit down and start writing if I wanted to publish a book.)

G.E.’s funeral is tomorrow, down in the town where he went to and first taught in high school, Lexington. Afterward, I imagine there will be a long, long procession out to the tiny cemetery in his real hometown, Pleasant Hill, about three miles away. It will be by far the biggest event that would-be city, which started withering when the railroads bypassed it in the 1850s, has ever seen. G.E. and his grandfather and probably many others to whom he unearthed family ties have been cemetery caretakers there; we visited the spot together a couple of times a good 30 years ago; I think I was aware even then, when he was younger than I am now, that this was where G.E. hoped to come back to; not a patch of dirt in a swath of farm and prairie, but a place where his people were.

Feeling sad about the prospect of missing G.E.’s funeral, I picked up his book of poems. I thought, there’s got to be something in there where he talks about his own passing. I turned to the back of the book, to the section whimsically titled “Fear, Aging and Death.” And found this, dated 1990:

Grave Notes from the Underground

When I am dead,

who will enter this quiet sanctuary

and, speaking softly,

(Don’t shout!

I’m not deaf, you know.)

tell me the news I want to know?Did the Cardinals win last night–

and who was the winning pitcher?Did the bluebirds sing this spring

on the trail along Bluebird Lane?Has the Big One ever struck

San Andreas or New Madrid faults?

(And am I safe in Pleasant Hill?)Have politicos on Capitol Hill

yet understood the limits …

… and limitations … of capitalism?Do my friends I loved so much

… just once in a while, perhaps …

call or visit each other?From the knoll and the gnarl of Old Flat-top,

does anyone ever watch, as I once did,

the sunsets west of the sanctuary?

Or the April sunrise on the trail

as it enters Canary Clearing?Does a cool breeze still stir the air

under the sinuous branches of Old Flat-top?Do Browns and Boggs still gather

for reunions in July?

(Or do they go their separate ways,

ignorant of the roots that nourished them?)Is warmth still there at one-three-four

on Dogwood Drive?

Is someone nurturing those

in need of nurturing?Who came to say goodbye

as I lay freshly dead?I know, I know.

I can’t reply.

Nothing has really changed.

I rarely had a chance,

when lifeblood-flowed and tongue was ripe,

to sneak a word in edge-wise.Hey, take it easy there.

Your clomp’s so hard it’s apt to wake the dead.More on G.E. Smith

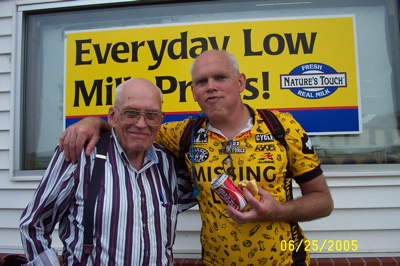

Happy 80.5, G.E.

A Teacher

In Which We Gather by the RiverTechnorati Tags: g.e. smith, illinois