Cutting to the chase: I just turned 70. To celebrate the occasion, Kate and I came to Chicago (where I’m writing this) to visit family and friends. A brief travelogue:

April 1

We flew from San Francisco to Chicago’s O’Hare airport. The first minutes of that flight take you over Oakland or Berkeley. On our April Fool’s Day trip, we had a nice view of the soon–somewhat desolate-looking Oakland Coliseum and Arena complex — former home of the Oakland Raiders and Golden State Warriors (and soon-to-be-erstwhile home of the Oakland A’s, who will decamp to Sacramento as they await construction of a stadium in their alleged eventual home in Las Vegas).

April 2

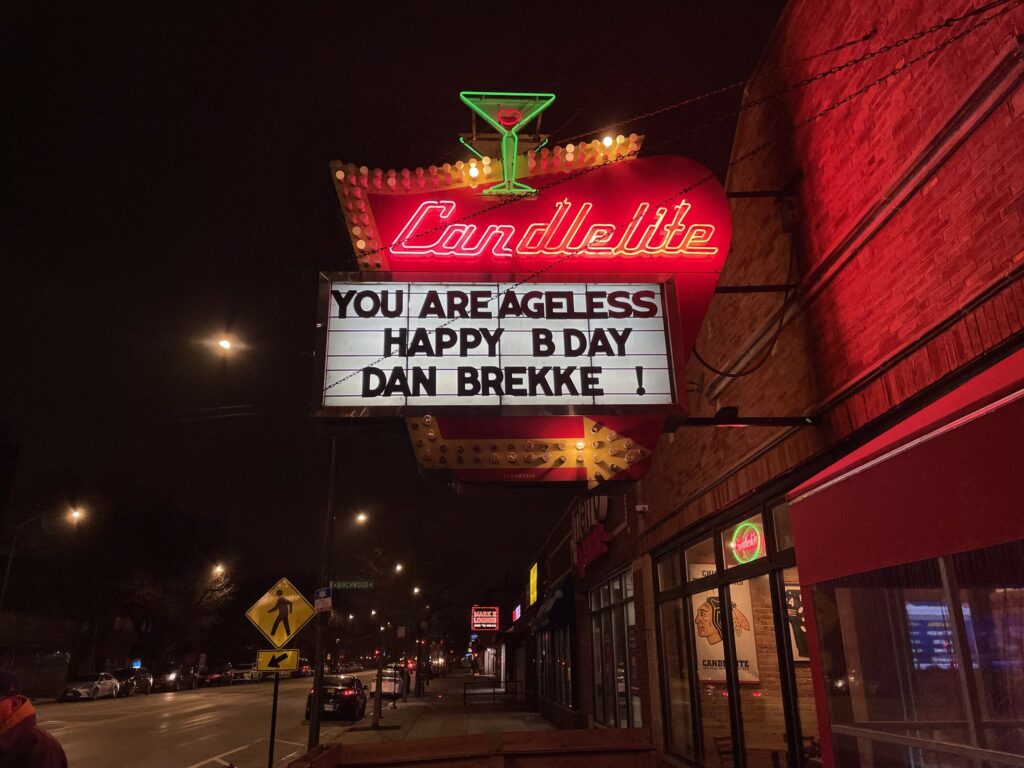

The big day. Thanks to my sister Ann and her husband Dan, I got my name in lights. We had a great time, including a trivia quiz in which I stumped the room by asking which two rivers merge to form the mighty Illinois River.

April 3

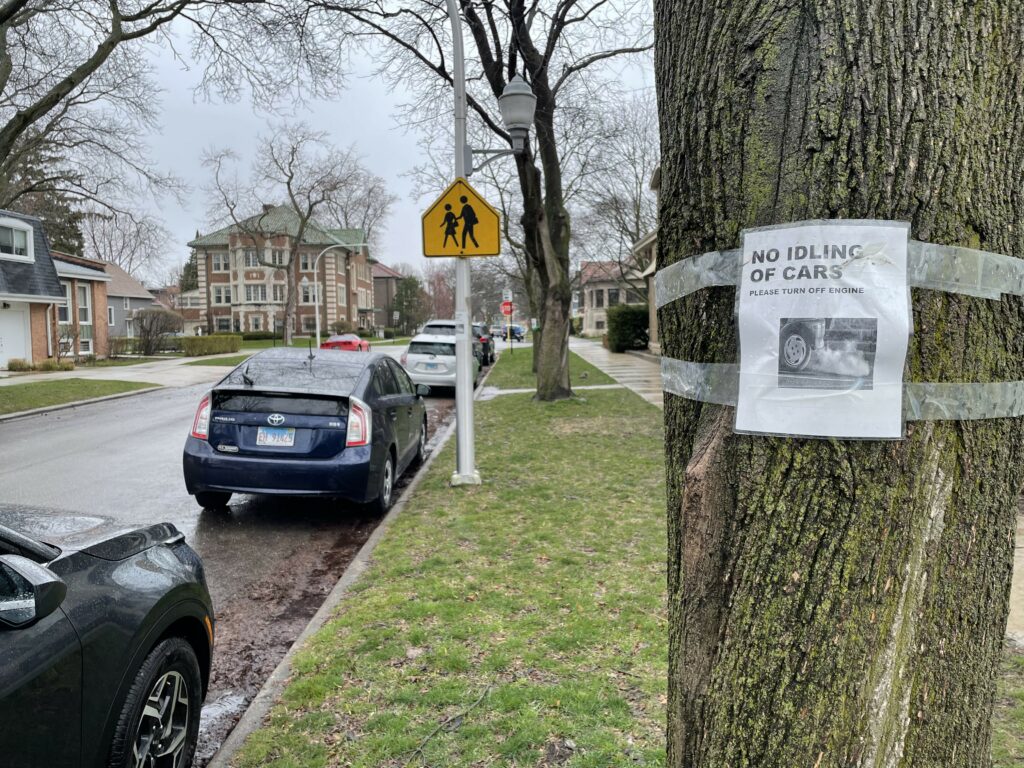

It was rainy and cold, with some intermittent snow flurries, our first three days in Chicago. I think my big activity of the day was driving my brother John to the airport for his return to Brooklyn. The picture? A local resident schools neighbors on automotive etiquette. This day also featured a visit to Pequod’s Pizza on North Clybourn.

April 4

On Thursday, the 4th, it was dry and a little warmer with occasional splashes of actual sunshine. Our son Thom was getting ready to fly back to Los Angeles. But first: We needed to find Italian beef sandwiches. First stop: Mr. Beef, on North Orleans, a place you’ll kind of know if you’ve watched “The Bear.” The restaurant was closed to accommodate film crews working on the show’s third season. Our backup spot was Al’s Beef on West Taylor Street,

April 5

On Friday, the 5th, we went down to the south suburbs to meet one of my high school writing teachers, Mort Castle, and his wife, Jane, at Aurelio’s Pizza in Homewood. Did I remember to take a picture of this Crete-Monee High School reunion? No. And neither did they. Later, Kate and I wound up at the Izaak Walton League’s Homewood Preserve. Note blue skies and evidence of direct sunlight.

April 6

On Saturday, the 6th, we drove out to the Fox River valley to see my high school German teacher and longtime friend Linda Stewart. She moved back to the town of Geneva, just up the road from her hometown of Aurora, in 2023. Also pictured: her dog, Pecan.

April 7

On Sunday, the 7th, we joined the throngs traveling to view the total solar eclipse happening the next afternoon. Our destination was Indianapolis and the home of my high school friend Dan Shepley and his wife, Paula. I had discounted the possibility that there’d. e a lot of traffic, but heading down Interstate 65 from northwestern Indiana, I discovered how naive I was. Stuck in one especially gnarly traffic jam north of the Kankakee River, we got off the interstate and made most of the trip on two lane roads heading south and east. Among the casual sightings along the way, a wind turbine being erected south of the town of Monon. We made it to Dan and Paula’s eventually.

April 8

Eclipse Day. We hung out at Paula and Dan’s all day. The sky show lived up to the hype, and the show on the ground, featuring neighbors who turned the event into a partym was good, too.

April 9

On Tuesday, the 9th, we wended our way back to Chicagoland, sticking to back roads until we suddenly realized we needed to get on the interstate (I-55 in this case) to get back in time for an online appointment Kate had.

April 10th and 11th? To be continued …