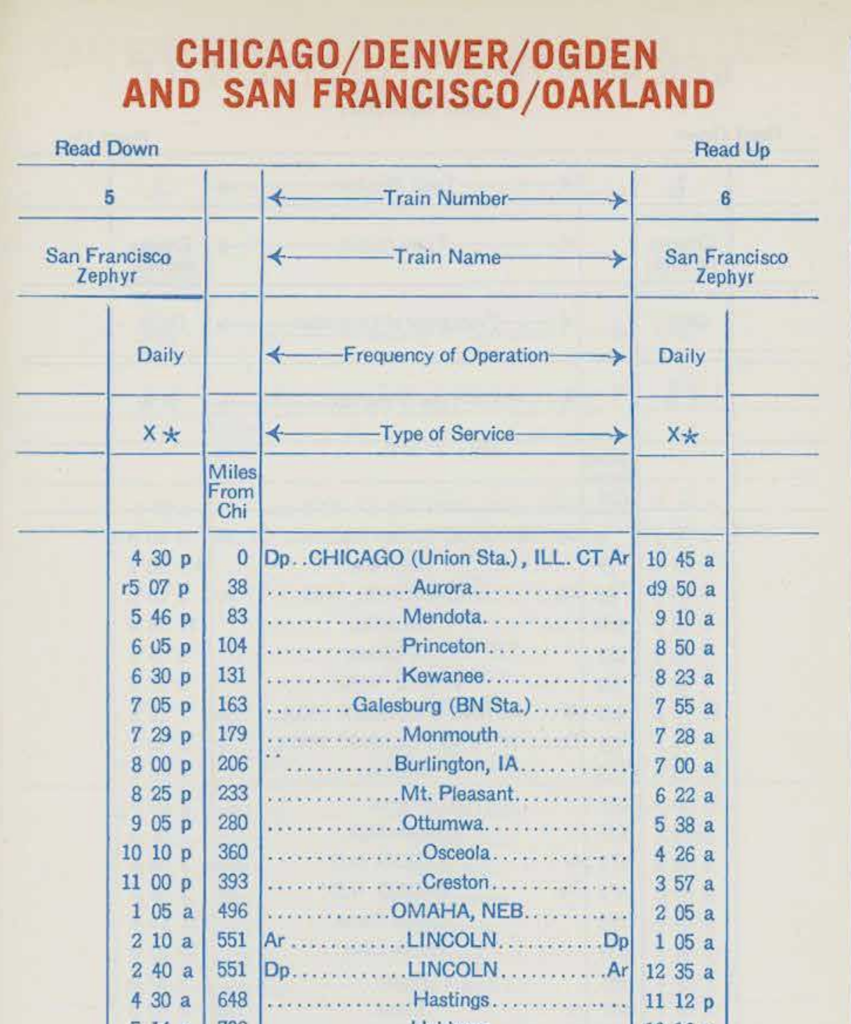

Part 1 covered the San Francisco Zephyr trip from Chicago to Denver. Part 2 took me from Denver to around Evanston, Wyoming — the southwestern corner of the state. This part —the last! — picks up with me in the dome car — a car with expansive windows and skylights to accommodate meditative scenery gawking — sitting in what I describe here as a “lounge” — part of the car that was arranged in side-facing sofas.

***

I had been watching a couple in the dining car. The woman, a sort of plain-faced New Englander in her late twenties, now sat across the aisle from me in the dome car. The guy with her, probably in his mid-thirties, was suave Tom Wolfe radical chic: uninflated.1 He was leading her along, she was laughing and having a good time, and I thought, “How nice.” He was making excellent progress when a third party arrived on the scene.

The new arrival was a writer for a New Jersey paper, and had dropped in a brief conversation with Rodeo and me that he’d been to the North Pole. He was carrying a copy of “Luce and His Empire” with him, which he would momentarily open when he closed his mouth.

Well, he arrived, and I thought with interest that Tom Wolfe could be counted out of this business. The writer (Newark, I’ll call him) was successfully putting his foot in the door, and Tom couldn’t stop him.

They talked about some trivial things, and came to the Donner Pass, recalling there had been a train marooned there in the 1950s (1956, I think2). Tom went off to fetch a bottle of port he had acquired along the way, and on his return joined a discussion between the girl (Boston), Newark, and a guy on my side of the aisle on the expansion and contraction of freezing liquids. My friend was really mixed up about what he was saying, and Tom, Newark and Boston were finding him amusing.

Then they got back to Donner Pass.

“When was that? 1952?”

“1956, I think.”

“Yeah, that’s where the digger Indians sat watched the Donner Party go through their thing, isn’t it?” the guy next to me said.

“What?”

“The digger Indians just hung out up there and watched the people eat each other, man.”

“But Indians don’t ‘hang out.'”

And that comment by Tom evidently offended my neighbor, because he didn’t participate in the conversation of the wine drinkers (Newark had graciously accepted his own invitation to share the wine with the romantic couple) except to add a comment about “Governor Ronald Raygun.”

I had been watching the land move by outside while picking up snatches of this repartee, and now we were in Utah. The hills were now mountains of rock, there were canyons, and snow-covered streambeds below. We were in the Rocky Mountains.

The guy next to me asked if I wanted a beer, and I said, “OK.” He was a tall guy who was also riding in my car; with glasses, red hair, and a red beard. He came back, and we drank our beer, and told each other where we were going, where we were from, etc. He had come from Chicago and was bound for Frisco.3

We talked about the deepness of the moonlight on the mountain, and “hanging out” there, and a lot of good things. His name was John Sweeney, and his father was a Chicago cop, Tom Sweeney, and had been in Studs Terkel’s book “Division Street.”4

I went for a second round because John was, as it developed, tripping. Amazing! No wonder he had been having a struggle with freezing liquids. We continued to watch and talk and everything, and I was getting a little drunk and liking it.

We talked about a lot of things you talk about in Chicago: WFMT, what a great and valuable thing it is; the police, whom John didn’t like at all; the crooked government and the beauty of the lakefront. And hanging out.

Some observations he made:

“Hamm’s is a lousy scab beer.”

“During the King riots, I was driving a junky old Buick, and it broke down on the Kennedy expressway and I had to get off at Cabrini-Green. There were squads rolling down the street, and dudes poking shotguns out of windows. I figured I had more to fear from the pigs than from the dudes around there. I’d be driving down the street in this old beat-up machine, and they were running alongside the car telling me ‘right on!’ There was one place they were looting a liquor store, they ran up and were pushing beers through the window at me. It was all right, you know.”

Looking then at the rocks we passed, he’d say, “It’d be all right to hang out up there.”

The black and white bleakness of the Wasatch Range rose up in the moonlight. It was all rock, and black where there was no snow. The train rolled past the lonely towns on I-80, all under the moon — it was the moon, the country of Frederic Remington.

And every once in a while, the voices of Newark and Boston, minus Tom (who had taken a powder at the strong advances of Newark) drifted our way.

We found out that Boston was a scientist (macro-biologist, I think (?)) and was going to some sort of conference in San Francisco. Newark stuck to his journalist story (the Star-Ledger5), but was just taking a week off from his daily column to skirt around the country by train. How nice!

Then John told me that “the god-damn idiot who tried to tell me that Indians don’t hang out” had made advances toward him during the evening. So I related my experience [with the amputee], and we were both relieved to find out it had happened to someone else.

Newark was continuing his campaign, asking Boston (quite phallically) where the dagger on Orion was. “Where’s the dagger?”

The mountains rose higher, and as we made the approach to Ogden, two peaks jutted high above the plain we rode on. Black and white, you could see the deep snow in relief on their summits. They must have been 6,000 feet high, seemingly right behind the town of Ogden.

Street lights strung right to the base of the mountains; there was nothing but darkness above. Where there was snow on the ledges, you could see the mountains, but otherwise they hid themselves under the full moon and the stars.

We started out of Ogden on the Southern Pacific the third and last leg of the trip. Within half an hour of leaving Ogden and the Wasatch Towers behind us, we were starting over the causeway across Great Salt Lake. The water sparkled darkly, was uninviting; there were only snow- and brush-covered hills in the distance now, and despite the noise in the car, everything had an air of dead silence.

John had gone back to the coach, and I lay on the seat and looked through the panels of the dome at the stars, watched them wheel as the train rounded bends in the track. Pretty soon, having lost interest in the Boston-Newark affair, and being tired (and a little drunk), I went back to my coach to sleep. I saw no more of Utah, and slept until we were about 25 miles east of Reno, thereby missing almost the whole state of Nevada.

And waking up (it was Sunday) we were still beside Interstate 80 (now heavily laden with signs for casinos).

We stopped first in Sparks, Nevada (six miles outside of Reno) and I have no idea why. It was a dirty little town with little or nothing that made an impression (except the men, who all looked desert-tough Nevada types; were wiry thin and sunburned, wearing faded denim and cowboy hats).

Reno was a dump. I thought there was supposed to be something big and special about it, but I couldn’t see anything to justify its reputation. But there must be something there, because two hundred people boarded the train; these were all California week-enders I guess, most of them just couples, and a few who had come with their kids.

There was one guy I remember in particular, whom I saw as he was getting on. He was wearing a cream-colored western suit with string tie, white shirt, and matching hat. The shape of his head was what really made me notice him: it was as close to cubic as it could come, like a block of granite, and sat on an almost non-existent neck hidden somewhere in his shirt collar. Everything about this man suggested the image of stone: his heavy, squared jaw, his nose, his forehead, even his obsidian black eyes. He had his wife with him, but somehow I didn’t note any of her physical details. She could have had a face right off of Mount Fillmore6 and remained unimpressive beside her husband.

I ate a heavy breakfast amid all the weekend gamblers, and then went to the dome car, and sat with a couple from Laramie. The guy was a trainman, and was just on a little vacation with his wife, I guess. They didn’t talk to me much (or at all) and I really didn’t say much to them, either.

But the train was rising now, up the abrupt eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada. Creeks foamed down the hillside beside us, there began to be thicker stands of pine on the slopes, and there was a lot of snow as we climbed higher under still cloudy skies.

Up and up we went, through a tunnel and a switchback, and to the west blue sky could be seen. As we cleared four thousand feet the sun came out, the clouds were just a grey band below us.

The trees seemed to get bigger, the snow much deeper as we progressed toward the Donner Pass. I’d know what kind of trees they were, but they stood like spikes 180 feet high, with their branches laden with snow. There was snow standing two feet deep on the crossarms of the telegraph poles, making the oldtimer who’d gotten on way back in Cheyenne say, “The snow doesn’t stay like that in Wyoming, does it? We have that little breeze up there,” with his grin, and eyes watery from the brightness of the snow in the sun.

There was a man reading a book behind me, a book about this rail route, and he kept telling us what lay ahead — the snow sheds, tunnels, view of Donner Lake — and I sort of wondered what kind of enjoyment he was getting from it (perhaps an immense amount).

Soon after he announced we would be skirting Donner Lake, we were, two thousand feet above it. It lay frozen and cold, the only sign of life (and it was an outstanding one) was a string of cottages and summer homes along its shores.

My mother gave me a book entitled “The Donner Party” for my last birthday; it begins with the lines, “My name is George Donner/I am a dirt farmer…” and I thought of the dirt farmers from central Illinois who struggled here so long ago beneath the weight of an October storm.

The trees seemed there highest here, the snow the deepest. I said to the woman from Laramie, ” My God, those trees are hearty,” and she nodded. I felt tears welling in my eyes for a minute or two, but they didn’t roll down my cheeks, as I wanted them to. For a moment I saw or felt something there. I don’t know what: “My name is George Donner/I am a dirt farmer….”

The Southern Pacific wound through the mountains, now slowly down, and past a wreck. which re-inflated the Cheyenne old-timer with more story-telling energy. (Most of the stories I heard were about a train coming around the bend in a blinding snowstorm to find a wreck place inconveniently in its path).

We went through the clouds again, passed through Truckee8, and were headed for the Valley and Sacramento. I went to my coach and slept, waking up in Sacramento.

The sun broke out again as we went southwest toward Oakland, and it looked beautiful: many of the fields were under water; there were a few ducks in the flood (and thousands of decoys), and red-tail hawks glided in the sky between the soft green hills of the coast ranges.

The whole country, palm trees, bright blue sky with the purest white clouds sailing above, looked like a sort of paradise. (I’m not sure exactly what kind — advertisers’?). It reminded me of the part in “The Grapes of Wrath” where the Joads come to a ridge-top on Route 66 and see a Canaan-like scene before them. But it’s not clean; there is always something to remind you you’re in the middle of civilization: earth movers levelling a far off hill for a highway, or a junkyard overflowing with wrecked cars.

And we hit the bay and the tracks moved down alongside it. We passed lots of fishermen on the rocks (and the rocks were in the sun) who smiled and waved as we passed. We continued, farther and farther along the shore, and I thought, “Damn, this thing is big.”

On the highway next to the tracks we saw ads for all the motels in Oakland and San Francisco. We passed through refineries, and the Sherwin-Williams factory, through water-front communities and too-neat tract developments. “When do we get there?”

The train slowed, and finally stopped. Everyone anxiously asking, “Is this it?”

Then the announcement: “Oakland 16th Street Station.”

“This is it!”

Another announcement: “A bus will take you from here to San Francisco.”

I was very nervous all this time about my luggage [which consisted of a frame backpack and accouterments] — whether it would be destroyed or simply lost. But I saw it safe and secure on the luggage wagon outside.

I boarded the designated bus, and just as I saw them stow my pack, I was Rol9 outside. I climbed out, retrieved my luggage, and … California.

Notes

- The meaning of “uninflated” here is lost to time. Maybe I meant he was an “uninflated” — less than impressive? — version of Tom Wolfe? Your thoughts welcome.

- 1952, actually, which someone in the trio’s conversation says.

- “Frisco.” There — I said it. Possible explanatory circumstance: Maybe I was quoting my companion.

- After coming across this a week or so ago (January 2023), I went and found an online copy of “Division Street: America” and tried to look up Tom Sweeney. There’s no one in the book by that name. But there is an interview with a Chicago cop named “Tom Kearney.” Terkel says in his introduction that he had used pseudonyms for most of his interviewees, so my guess is that “Kearney” was actually Sweeney. Further evidence: In the interview, conducted in 1966 or so, Kearney mentions having a 22-year-old son. That would square with the age of John Sweeney, who I would guess was in his late 20s when we met in 1973.

- An actual paper in Newark, New Jersey. In 2023, I might have asked this person’s name and then looked up what he’d been writing.

- Fillmore? I think I meant Rushmore.

- The work (mis)quoted is indeed called “The Donner Party,” by George Keithley, who taught for decades at Chico State. It’s a book length poem about the epic of suffering endured by said group of emigrants from the Midwest to California in 1846-47. The actual first lines are: “I am George Donner, a dirt farmer/who left the snowy fields/around Springfield, Illinois/in the fullness of my life/and abandoned the land/where we had been successful/and prosperous people.” I note that the way I quote the line matches precisely the meter of “my name is Jan Jansen/I live in Wisconsin….”

- I’ve placed Truckee on the wrong side of Donner Pass. Maybe I was referring to Colfax here

- Rol Healey, a childhood friend of my mom’s from the 8300 block of South May Street in Chicago, met me in Oakland. Rol was a high school English teacher in San Jose who put me up during my Bay Area stay. He was a fantastic host — that first night in the Bay Area, he and a fellow teacher took me over to North Beach and City Lights Books. We also visiting Monterey (pre-aquarium), San Juan Bautista, and Yosemite. Rol was one of the reasons I came away with the idea that the Bay Area was an amazing place.