There was a time — starting the moment George Washington left office — that being a military heavyweight wasn’t seen as one of the big qualifications for being president. The Civil War (six) and World War II (six) produced the highest number of president veterans–most who served as generals. If there’s a pattern here — military service or expertise turning into excellence as commander-in-chief in wartime or in peacetime — it escapes me.

George Washington: Trenton was one of his greatest hits.

John Adams: Learned to be commander in chief on the job.

Thomas Jefferson: Learned on the job.

James Madison: Learned on the job–fought actual war.

James Monroe: Learned on the job.

John Quincy Adams: Learned on the job.

Andrew Jackson: Knew his way around a battlefield. (References.)

Martin Van Buren: Learned on the job.

William Henry Harrison: Did someone say ‘Tippecanoe’?

John Tyler: Learned on the job.

James K. Polk: Learned on the job. Enthusiastically.

Zachary Taylor: Soldier.

Millard Fillmore: Learned nothing on the job.

Franklin Pierce: Mexican War combat veteran.

James Buchanan: Learned on the job.

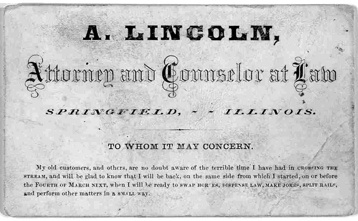

Abraham Lincoln: Learned on the job (served in Illinois militia during Blackhawk’s War).

Andrew Johnson: Learned on the job.

U.S. Grant: The Civil War brought out the best in him and the blood out of everyone else.

Rutherford B. Hayes: Civil War combat veteran.

James A. Garfield: Civil War combat veteran

Chester A. Arthur: Civil War quartermaster.

Grover Cleveland: Avoided Civil War draft by paying a substitute. Learned on the job. Twice.

Benjamin Harrison: Civil War combat veteran.

William McKinley: Civil War combat veteran.

Theodore Roosevelt: Noted equestrian with enthusiasm for Cuba.

William Howard Taft: Learned on the job.

Woodrow Wilson: Learned on the job.

Warren Harding: Learned on the job.

Calvin Coolidge: Learned on the job.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Former assistant secretary of the Navy.

Harry S Truman: World War I combat veteran.

Dwight D. Eisenhower: Ike. Mentioned something about a “military-industrial complex.”

John F. Kennedy: PT-109.

Lyndon B. Johnson: World War II combat veteran (Army).

Richard M. Nixon: World War II, Navy; played mean game of poker.

Gerald Ford: World War II combat veteran (Navy).

Jimmy Carter: Navy nucular engineer.

Ronald Reagan: Learned on the job (warmed up dispatching National Guard to Berkeley).

G.H.W. Bush: World War II combat veteran (Navy).

Bill Clinton: Otherwise engaged during Vietnam draft. Learned on the job.

G.W. Bush: Air National Guard (1970s); carrier landing (2003).

Technorati Tags: presidents