An immortal household exchange from the distant past:

Kate to one of the kids: I can’t play right now. I’m not here just to entertain you.

Kid: Why are you here, then?

(Kate and Dan laugh.)

Kid: No–really. Why?

"You want it to be one way. But it's the other way."

An immortal household exchange from the distant past:

Kate to one of the kids: I can’t play right now. I’m not here just to entertain you.

Kid: Why are you here, then?

(Kate and Dan laugh.)

Kid: No–really. Why?

My sister Ann reminded me, by way of a Facebook post, that yesterday, the 26th, was Mom’s birthday. She would have been 83. That’s her in a shot my dad took in May 1964, when she was 34. She’s posing in our Park Forest living room, and I think the occasion was that Dad was trying out a camera he had bought recently, a Minolta twin-lens reflex model. There’s a series of other shots taken the same time; my brother Chris scanned them after Dad died earlier this years.

So much of this scene is evocative and immediate: The painting, by a family friend, was a fixture in every place we lived (and now hangs in Ann’s house). I know Mom was sitting on a slat bench that also made it from house to house through our infrequent relocations (it’s at Ann’s or Chris’s now). The vase of pussy willows over Mom’s right shoulder–I don’t know where that came from. But I can see the living room, with a black linoleum floor, half-paneled in redwood, a set of bookshelves Dad had installed, the closet where his stereo system resided, the Danish modern chairs and love seat and round coffee table, the doorway into the kitchen, the hallway back to our bedrooms, the picture window looking out onto the lawn, which sloped down to the street, bordered on the far side by a field and woods.

And part of this scene feels odd and distant, almost false: There’s a tension in Mom’s pose, for one thing. She had a way of putting on a face sometimes in a way that I don’t see in photos taken much earlier or much later in her life. I might be seeing something that’s not really there, but I know what she and my dad had been through at this point: raising five kids, for one thing, and the death of one of them, and other troubles that I feel are barely contained beneath this serene-looking scene.

And also I know what’s to come for her. She’s about to go into psychoanalysis, get a driver’s license, join Operation Head Start, move out to the woods into a new home, become a foster parent to untold numbers of stray dogs and cats, and help organize a campaign to save the forest from an ambitious local developer. She’s going to use her considerable intellect and talents as a newspaper reporter, go back to school, and work in several other challenging jobs. She’s also about to confront deep and lingering depression, the reality of a husband and brother sinking deep into alcoholism, several angry adolescent boys and a daughter who was pushed into the background by all of the above.

It feels like all that is hiding inside the frame here, somewhere behind that composed smile.

A few days ago, our son Thom told me a soldering iron would be arriving at our house via UPS. “A soldering iron?” I probably replied. He said he had a project he wanted to do–assembling some small external iPhone microphone kits–and we needed the soldering iron for that.

So, today was the weekend, and Thom came over, and we spent part of the afternoon and early evening assembling the mics. I was enthusiastic because I (and many, many others) have started playing around with different ways of recording sound on the iPhone for radio story production. One of the big issues, though, is controlling distortion in loud environments. This microphone–it’s called a bootlegMIC and was designed by Open Music Labs–plugs into the phone’s headphone jack. Essentially, it’s an attenuator–it uses a resistor to reduce the audio signal the phone’s built-in mic has to handle and thus avoid distortion.

Thom made one, and it seemed to work fine. I built mine, with his assistance (the last time I handled a soldering iron=maybe never). Thom built a third mic (above) for a friend. In the picture, he’s holding the jack end of the device; the microphone is at top.

Moby, the van, visits Yosemite’s White Wolf Campground in August 2010.

I’m reading a book right now called “Shop Class as Soulcraft,” by Matthew B. Crawford. It makes a convincing argument that we’ve largely banished what used to be called “the manual arts”–generally speaking, skills developed using tools, making stuff, and fixing stuff–at a large cost in lost competence and career opportunity and, in both tangible and intangible ways, engagement with our world of machines.

There’s a lot more to the book than that (if you want a sample, here’s the original essay upon which it’s based). For instance, it questions some of the essential assumptions of current assumptions about the purpose of educations and the role of people in the economy. But the part that immediately resonates with me is the piece about learning to fix things yourself, and actually doing the fixing.

It’s not that I don’t know how to fix some stuff. I’ve done a reasonable amount of work on my own bicycles and have even (it’s a sensitive enough job I think of it as “even”) overhauled a bottom bracket. Once upon a time I did some of the demolition work on what seemed at the time a very ambitious kitchen remodel. Of course, the part some friends still remember is how long our kitchen was a construction zone, with no ceiling and a nice view right up through the joists to the rafters (we eventually hired folks and got some help from skilled neighbors to finish the job).

For the most part, a complicated fix is a fix that I feel most comfortable handing to someone else, especially when it comes to cars. I’m competent to check the oil (and have changed it once or twice, though, wow, it seems like oil filters are getting harder and harder to reach). I have replaced light bulbs and whole light units. I take pride in having handled my own tire chains in the slush and snow (once–and they stayed on). I know how to jump-start a car. When the Number 1 cylinder on our Toyota Echo started missing on a trip out to California from Chicago with my brother, I was able to follow the mechanic’s explanation of what was wrong (and what was needed to fix it permanently, as opposed to the temporary repair we got that’s still in place) despite his Texas Panhandle accent. But like most of us, I’ve never done a brake job or tuned up a car (is that something that’s still done?) or replaced a belt, much less removed and torn down and rebuilt an engine.

All of that became relevant in the last few weeks when our semi-beloved 1998 Dodge Grand Caravan SE (six-cylinder, 3.3-liter engine), which had performed relatively faithfully despite getting pushed hard for much of its life, suddenly developed a critical illness. For most of its fourteen and a half years and 208,515 miles, the most trouble it had given us was a transmission that balked at long mountain grades. That issue appeared during a drive up to Eugene, Oregon, in 2008, when at 70 mph on a long 6 or 7 percent grade into the town of Mount Shasta, the van suddenly shifted into a lower gear, which led to the engine turning at much higher RPM, which forced me to slow down, which led to the engine shifting into an even lower gear, which forced me to slow down even more. Luckily, I was coming to an exit, got off the highway, and managed to find a garage in town that quickly and cheaply diagnosed the problem via computer: a solenoid inside the transmission was fouled, and since the car worked fine on a test drive, we’d probably be OK (we were, except for one subsequent trip into the Sierra two years later). Aside from that, and the failure of a power steering pump once when I was driving home with a couple other cyclists after a 190-mile ride in the rain, the only real complaint I had with the car was its lousy around-town gas mileage.

But last month, the van suddenly overheated one morning when Kate was driving it to school. We had it towed to the garage that had been taking care of it the last five or six years. I figured that the water pump had finally quit. But the news was worse: a cracked head gasket. Fixing it would require taking the engine apart and installing a new gasket (and hoping that the head hadn’t warped as the result of the overheating that probably cracked the gasket). It would be a big-ticket item to fix–minimum $1,500, probably, and more than we figured the car was worth (though checking now, the Kelley Blue Book price on our wreck is $2,500).

Our first thought was to donate the van to some worthy organization. I like the one up in Marin County that’s working to save the last wild coho salmon stream on our part of the coast. But Kate had another idea. A family at her school needed a car. The mom, Mirian, volunteers a lot, and the dad, Carlos, is a competent and confident mechanic. They came over and took a look at the van, and Carlos thought it would be no sweat to get it running again. He also wasn’t put off by the long list of minor maladies we’d been living with–a cracked windshield, a windshield washer that no longer works, a rear vent window that no longer opens, one pretty significant dent where I backed into a tree, paint peeling from the roof, and the fact the car has its original transmission, which is at double its predicted life. He took in the list of problems one by one and smiled–he’d fix them.

I admit I had a moment, just a moment, where I thought, “Gee, maybe I ought to be able to take this on.” But the truth is–“Shop Class as Soulcraft” notwithstanding–getting this car back on the road would probably be a project that for me would last for years, anyway.

So today, Carlos came with a tow truck and took the van away. I went out and shot pictures of the departure, the end of our Grand Caravan Era. The van, which we nicknamed Moby when we bought it (because we also had a Ford Escort, nicknamed Toby), had made one cross-country trip; Eamon and I drove it to Chicago in June 2004 to help my dad move (we left at 5:30 on a Saturday morning and made it into Chicago at 10:30 Sunday night). I drove it up to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, back in 2007 with my friend, Pete, so we could test-ride the bike circuit used by the Ironman triathlon there (Pete did the race in 2008 and 2009). The van made more than two dozen trips back and forth to Eugene (1,025 miles round trip) when Thom was at the University of Oregon; we hauled stuff up there for his move-in in 2005 and back down when he graduated in ’08. Kate was driving the van on an excursion to Carrizo Plain back in May 2006 on the trip where she encountered and wound up adopting Scout (aka The Dog); he was initially too weak to get up into the car by himself. The last big trip we took in the van was in August 2010, when we went car camping in the Sierra (including a night in the Yosemite high country, pictured above) and did some extended bushwhacking along some Forest Service roads).

It’s gone, and hopefully it has more miles and adventures ahead for Carlos, Mirian, and their family.

When I was back in Chicago following my dad’s passing in late July, I went for a couple long walks from my sister Ann’s house to local cemeteries. It’s amazing how quickly you can cover six or seven or eight miles after you’ve set out for a stroll up there.

One day I wound up in Rosehill Cemetery, one of Chicago’s oldest, between Western and Ravenswood south of Peterson. Another day I walked up to Calvary Cemetery, a Roman Catholic establishment on the southern edge of Evanston that stretches between Lake Michigan on the east to Chicago Road on the west.

The Calvary visit was late in the day. On the way up there, I walked past a railroad viaduct that had some attractive sunlight shining through it. I stopped to see if I could get a picture that captured the light and shadows (I didn’t get anything worth keeping). What I didn’t spot when I first started shooting was a group of people on the sidewalk on the other side of the passage–two women, a man, and a girl of about 10. “You want to take my picture?” one of the women asked. I didn’t understand what she was saying and didn’t respond, so she repeated the question. “Sure, I’ll take your picture.” The man hung back, but the women and the girl posed briefly. I took a total of four or five shots.

I got an email address from one of the women; I sent these pictures there, though I never heard anything back. Unfortunately, I didn’t get any names, even first names.

Above, it’s the California Sister (Adelpha californica). We spent the weekend with our friends Jill and Piero in that part of Calaveras County where the foothills turn to the mountains, on a ridge south of the Middle Fork of the Mokelumne River. On Sunday, we walked down to Blue Creek, then walked up the stream a short way. This butterfly was hanging out and posed while I tried to get a picture.

Back at base camp, also known as Casa Della Montagna, a construction project was under way. Piero and Jill were building a small deck for a wood-fired hot tub. The underlying framework was a beautiful, asymmetrical web of beams and joists. I commented on the workmanship, which I always find impressive. Piero seemed to see it as more of a rough-and-ready carpentry job. He said, putting a new spin on an old proverb, “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the done!”

Kate and I spent the afternoon watching and occasionally lending our hands as Jill and Piero measured angles, cut planks, and screwed them into place. They were done by dinnertime.

(Click pictures for larger images.)

Since I always seem to be taking pictures, it seems natural that I started taking pictures of my dad on most of our visits the last few years. It wasn’t until late July, the week he died, that I looked back on what I had taken over the last year or so. I made several visits last summer, and then there was a long hiatus–from his 90th birthday weekend all the way until this past May. Over that time, his situation had changed. After a couple of episodes of pneumonia, his advancing dementia, loss of mobility, incontinence, and other issues, he needed round-the-clock nursing care. That meant he had to leave the home of my sister, Ann, and her husband, Dan, with whom he’d lived since the end of 2008, and enter a nursing home Evanston.

When he went into the facility, called Dobson Plaza, he was in pretty rough shape. He’d been there a couple of weeks by the time I visited in May and by then he seemed to have bounced back a little. I say a little: He was quite weak, confined to a wheelchair, and needed assistance for virtually every daily chore beyond feeding himself. He undertook that task with competence but little enthusiasm–maybe because his intake was reduced to pureed meals because he was having difficulty swallowing and was in danger of aspirating food and triggering another lung infection. There wasn’t much of a question that we–Dad, my siblings and I–were now waiting for the next turn, and the next turn would not be for the better.

He was losing weight, and by early July that prompted a discussion with his doctor of what kind of intervention might be appropriate (they could give him a drug of some kind to stimulate appetite). Before that conversation could reach a conclusion, I think, he suffered another bout of pneumonia and was taken up to Evanston Hospital (from my impression not a bad place to wind up if you’re in that part of the world and need medical attention). By coincidence, my brother John and I had arranged to visit at this time–he from New York, I from California–and got into town a couple days after he was hospitalized.

The news turned out to be worse than pneumonia. He was suffering congestive heart failure and tests detected the presence of fluid in the chest cavity around his lungs, signaling some other infection or even a malignancy. John and I got to Chicago late on a Saturday night, and Sunday we had a family meeting with Ann and our other brother, Chris. Since Dad had been suffering dementia, Ann had power of attorney, and among us we agreed that the course of action Dad would have pursued, or that our mom would have pursued if she’d been around, was hospice care. In essence, that meant ending aggressive attempts to fight the infections and other issues Dad was suffering from and focusing instead on taking what measures we could to make him comfortable in his remaining time. And that time? Well, he was about five weeks short of his 91st birthday and his body had kept going through a lot of hard stuff. We didn’t know whether we were looking at a day, a week, a month, or more.

Then Chris, John, and I went to see him in the hospital. Since I’d seen him in May, I felt I was prepared for what we’d see. And I wasn’t shocked to see that he was gaunter than he had been or that he looked really knocked out. But it also struck me for the first time that I was in the presence of someone who was dying, and that the death was not some abstract thing out there somewhere in the future. It was near.

Although you can fool yourself. You see someone that you’ve known your whole life, someone who has kept going through some pretty rough stuff, and anything positive–an alert look, a quick response to a question, a willingness to eat–becomes an encouraging sign. We spent about eight hours with Dad in his room, and I think we all were constantly aware of the monitors keeping track of his heart rate, his oxygen levels, his respiration. He dozed a lot, and a couple of times he seemed agitated as he started awake. His heart rate and breathing seemed to fluctuate, and I thought, “Is this it?” Then he ate a decent portion of the pureed chicken and mashed potato dinner that was on the lunch menu. I said after he finished, “It’s time to say ‘Takk for maten’ “–Norwegian for “thanks for the meal.” He glanced my way and said, “Not really.” It sounded like a dry Nordic reply.

The hospital sent him back to Dobson, the nursing home, for the hospice care we had set up. We visited each day, starting on the Monday he returned there. Dad seemed to be holding his own despite what we knew, or had been told, or suspected, was happening beneath the surface. He ate a little. He seemed to like his coffee. He seemed to like our being there. He seemed to respond when we played him some of what we remembered as his favorite classical recordings. He seemed absorbed when I began reading aloud a tale of the Norse in Greenland (I thought he’d identify with a Viking story).

And then, several days later, I headed back to California. I had an idea I’d ask for a leave to come back to Chicago and see out Dad’s last days. But things moved fast after I departed, and he died the next day. As I said several weeks ago, I missed him already. I still do. The best memory I have of that last week, though, is the time we all spent together as a family, and the best thing that happened was that we all worked together at least in those few days.

I only meant to write enough to provide some context for the pictures that follow, which in a small way record his passing. There’s still a lot left to say. Sometime. Soon.

With my dad’s recent passing, and having made several (unrelated, except for my mood) recent visits to Chicago cemeteries, I’ve been thinking about epitaphs. Webster’s defines epitaph as “1. an inscription on or at a tomb or a grave in memory of the one buried there. 2.: a brief statement commemorating or epitomizing a deceased person or something past.”

Most of what’s carved on graveyard monuments is pretty simple: names, dates, and relationships. Beyond that, most of the common people buy at most a brief fragment of a sentiment. In Catholic cemeteries, I’ve seen a lot of “My Jesus Mercy.” On my dad’s parents’ grave, In largely Scandinavian-American (and Lutheran) ground, the message is “Christ My Hope.”

But except for the expense involved–I think we’re paying $150 to have “2012” carved on my dad’s headstone–I think a secular message might be reflect more the concerns of today’s future deceased Americans. I’m thinking of phrases that reflect the preoccupations of most of us for most of our waking life: Phrases like:

Has anyone seen my keys?

Do you mind getting me another beer?

It’s time to get up already?

Turn here. No–here!

Have change for a 20?

Hey–there’s no toilet paper in here!

Sorry I’m late–traffic was terrible!

I meant to get in touch.

Don’t blame me.

What time is it?

Yeah–I’ll send that check tomorrow.

Later–we’ll discuss it later.

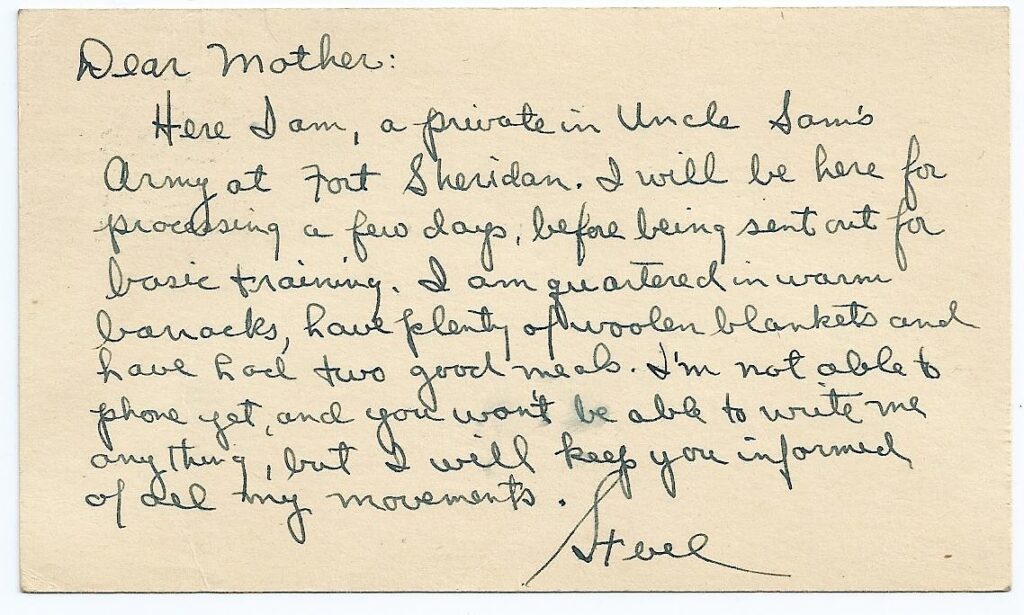

It’s my last night in Chicago for a while — now early morning, actually. I’ve stayed up way too late looking through a collection of letters Dad wrote when he was in Army basic training. That was in 1946, after World War II ended. The story we heard growing up, and I’ve got no reason to doubt it, is that he tried to enlist at the outset of the war but was rejected and rated “4F” because he had a punctured eardrum. That condition gradually healed, and he was rated fit to serve and drafted in late 1945 and inducted into the Army in January 1946.

Part of his parents’ legacy that I heard about growing up was a collection of more than 100 letters my grandfather, Sjur Brekke, wrote my grandmother, Otilia Sieverson, during their courtship and early marriage in the first decade of the last century. (The courtship started at a Lutheran parish in Chicago, where he was a visiting minister in training and my grandmother’s family were charter members. Sjur was a smooth operator. We have a note he wrote to Otilia on the back of a business card; the subject was a couple of volumes of commentary on scripture he had “taken the liberty” of loaning her. He also offered to hook her up with more such volumes if she liked the first two.)

Sjur died in 1932, when Dad was 10, and he said his mother not only hung onto all those letters, but read and re-read them. She numbered them and kept each one in its original envelope; she wrote key phrases from each letter on the envelopes, apparently her way of prompting herself as to the contents. When she died in 1975, the letters passed on to my dad. They’re among the papers he left behind. (If you’re wondering about my grandmother’s letters to my grandfather, well, so do we. She destroyed them at some point after he died.)

What I didn’t know, though, was that my grandmother kept a second letter archive. She saved all the correspondence Dad wrote during his year-plus in the Army, starting with a postcard from Fort Sheridan, north of Chicago, the day he arrived for processing.

“Dear Mother: Here I am, a private in Uncle Sam’s Army,” he began. I’m guessing the postcard was something the Army had its new inductees do to reassure the home folks they were OK.

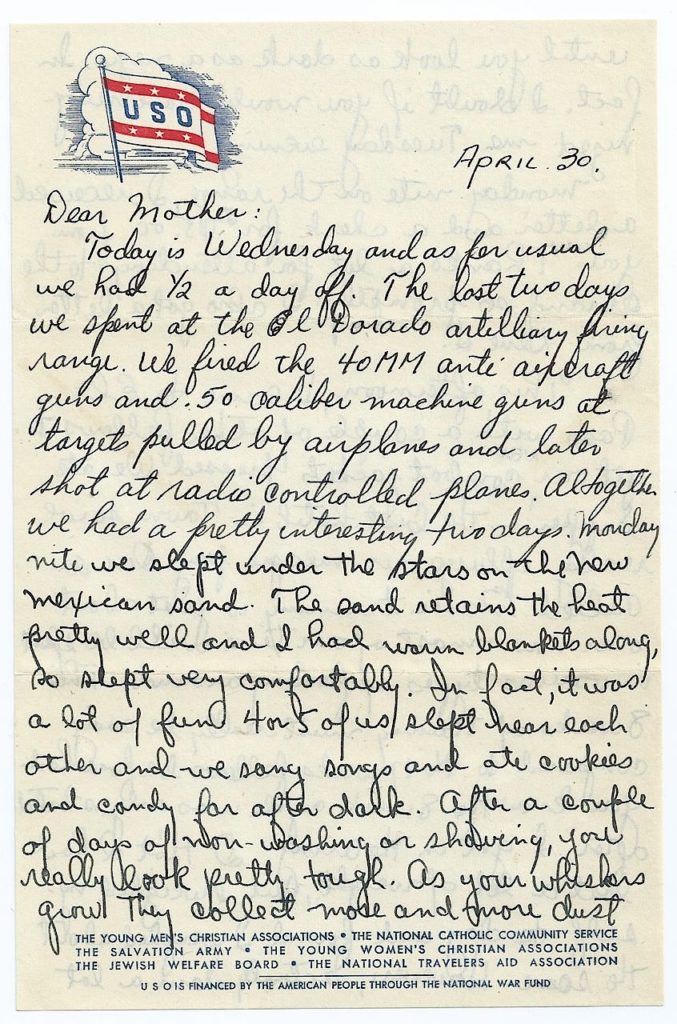

There are about 75 of these letters in all — 20 or so from his time in basic training, which took him to Fort Bliss, near El Paso, Texas, and another 50 or so from his time serving in the occupation of Germany.

Leafing through the basic-training letters the other day, I felt like I was getting to know a person about whom I had only heard vague accounts. One thing comes through very clearly: the Army wasn’t really for him. He was interested in learning what he could in the ranks — he was being trained in a field anti-aircraft battery — but he had his own agenda, which always seemed to come back to music and whether he could finagle a way into an Army band (he couldn’t and didn’t). He also loved the opportunity to see a part of the country, dry, desolate West Texas, that was completely new to him.

I read a few of the letters aloud the other day to my siblings. One in particular delighted us. Dad describes a trip up to an artillery range to fire anti-aircraft and machine guns at aerial targets. It sounds like he enjoyed that somewhat. But he also liked the chance to camp out:

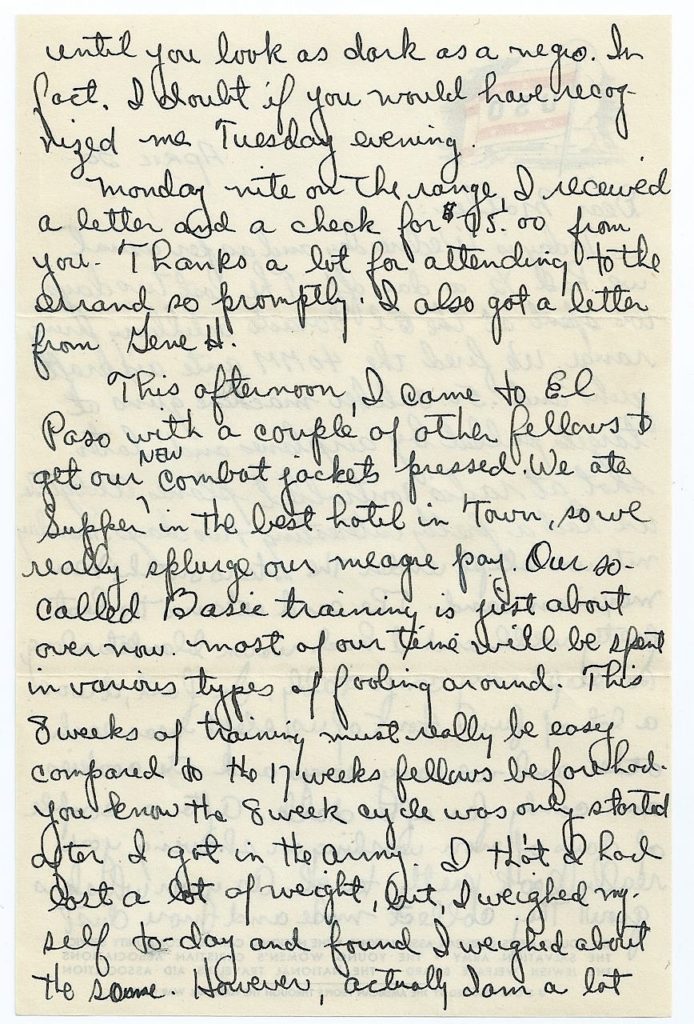

“Monday nite we slept under the stars on the New Mexican sand. The sand retains the heat pretty well and I had warm blankets along, so slept very comfortably. In fact it was a lot of fun. 4 or 5 of us slept near each other and sang songs and ate cookies and candy far after dark.”

Sounds like a kid at camp. He was also thrilled to go without shaving or bathing and said the grime made him “look as dark as a negro” (of whom there were none in his unit, of course). I’m not sure he ever really had any significant outdoors adventures before this. His parents were older and given to recreations like attending revival meetings. During an extended stay in Los Angeles in the early ’30s, their idea of a Sunday outing was to take Dad to see Amy Semple McPherson preach at her Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

The scan of the full letter is below.

We will be some time going through the archive of pictures and other effects our dad left behind. There’s a lot there I don’t remember having seen before. For instance, my brother Chris brought out a binder of transparencies last night that included some stunning shots of our mom during their engagement and of my dad in the years before that. I’m posting a couple of my favorites from other times here.

Above is a shot that surfaced in the last decade or so. That’s Dad, at almost four months old, on December 26, 1921, which happened to be his saint’s day. His parents lived in Alvarado, Minnesota, a village just up the Red River of the North from Grand Forks, North Dakota. There’s something in the way my grandmother is bent over him, showing him that little ball, that seems almost profoundly gentle, attentive, and caring. (I think this is partly because she’s the one in focus here, not my dad). That short northern Minnesota winter daylight that just barely plays across her forehead also gives a feeling of a fleeting moment captured.

The picture below is one of Dad with my son Eamon, his first grandchild. I think Eamon was about eight months old when my brother Chris took this during a brief visit. I’ve always been struck by how serious they both look. It’s a beautiful picture of the two of them.