Last night, I started to write a long, drawn out something about Cindy Sheehan and about the vigils being held across the country tonight. Well, without going the long, drawn-out route: Go out to one of the vigils. Sure it’s political. But regardless of what you think about the war, it’s a pretty direct and visible way of expressing concern about its human cost (easy for me to say — it looks like Berkeley will be full of vigils this evening). And not that this is of any practical value, really, at this late moment: If you want to find a vigil near you, check the directory on MoveOn.org.

Evil Counsels

Tonight’s topic — what is it again? It’d be great to tee off on the National Abortion Rights Action League’s misguided and idiotic TV ad against John Roberts, Bush’s nominee for the Supreme Court. Politics aside, if you can’t beat someone with the real record of their deeds and opinions, your fallback position really shouldn’t be to lie and distort and fabricate. Leave that to the pros on the other side.

But no, that’s not the topic. I could hold forth on Schwarzenegger, our very own blockhead Führer; he provides lots and lots of bile ‘n’ outrage material. And then there’s Bush: Every soldier’s mom’s best friend.

I have something more abstract on my mind. Here it is: Whitney v. California, decided by the Supreme Court in 1927. The case concerned a young woman from Oakland, convicted under a state law that outlawed “criminal syndicalism”; in practice, that meant the Communist Party and similar organizations were simply illegal, and having anything to do with them could be a felony. Miss Whitney, as the court’s opinion refers to her, was found guilty for doing no more than attending a party convention; that’s because the party in question advocated the overthrow of the capitalist system. The Supreme Court upheld her conviction on technical grounds; the majority opinion also held that the law was an acceptable exercise of state power to address a public danger and did not restrain the rights of free speech, assembly, and association.

Justice Louis Brandeis wrote a concurring opinion. He acknowledged in passing his acceptance of the technical grounds for upholding Whitney’s conviction. But his real purpose was to attack the law and the intolerance of free speech it reflected. It’s a ringing articulation of the importance of unrestrained debate in a democracy, and it’s widely celebrated as such. Check Google for “Whitney v. California,” and you’ll come up with about 9,000 hits. The U.S. State Department includes the case background and the Brandeis concurrence in its list of “basic readings on democracy.” I wonder how many people in Bush’s cabinet or the Congress have read it.

The opinion might be hard to digest in an age where some consider even soundbites on serious subject a little too weighty for some audiences to handle, But, in the context of Supreme Court writing, Brandeis is succinct and crisp. In current parlance, the whole concurrence is a highlight reel. Just one passage:

“Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties, and that, in its government, the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end, and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness, and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that, without free speech and assembly, discussion would be futile; that, with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government. They recognized the risks to which all human institutions are subject. But they knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

I never intended to come back to John Roberts and that abortion-rights ad. But there it is: “The freedom to think as you will and speak as you think.” What that means today is blasting away at your foes without fine attention to details like how all the facts, if you have any, might fit together. There’s not enough respect for, or faith in, the other side of what Brandeis suggests: “The fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

Catchy

August 6

At the tail end of the day — actually, tale end would work just as well — a moment’s pause to acknowledge the Hiroshima anniversary.

On one of the bike club email lists I subscribe to, one mostly for Berkeley folks and our ilk, one member sent out a mildly worded note that he planned a ride out to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory today to reflect on “human intelligence and human stupidity.” Good for him. Then, to underline his feelings, I guess, he appended a simplistic screed copied and pasted from someplace on the Web that declared that the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the “two worst terror acts in human history.”

That set off a chain reaction of responses that fell into two familiar camps:

–It was essential to use the bomb to avoid the slaughter that would have attended a U.S. invasion of Japan’s home islands. And besides, war is hell. And here were similar or worse atrocities and mass deaths during the war, some due to Allied bombing.

–Japan was about to collapse. The argument about preventing mass casualties is a myth. The bombings were entirely avoidable and amount to mass murder, plain and simple.

At one point, I would have veered toward the second camp. And I still can’t accept there was no acceptable alternative to dropping the bomb on a virtually defenseless civilian target. That being said, it’s disappointing that the discussion is reduced to such absurd oversimplifications and dominated by the need for an uncomplicated answer.

Easy for us, most of whom have no direct experience of the magnitude of violence unleashed in modern warfare to try to justify or condemn the bombing. The reality was terrible, and terribly complex. Just one example: The immediate backdrop to the bombing was the battle of Okinawa. Three months. Two hundred fifty thousand killed; 100,000 civilians killed. There was good reason to dread the next step in an invasion of Japan.

As I said, I can’t buy that dropping the bomb was the only option. But what did the decision really come down to? Callous disregard for life? Desire to avoid sacrificing U.S. troops in a bloody invasion? Reckless use of a lethal and perhaps imperfectly understood technology? Lasting animosity for a nation that hit us with a sneak attack? Underlying racial and cultural hatred? Desire to show the Soviets what would be in store for them if they got out of hand? Impulse to do something, anything to finish off a fierce and much-feared enemy?

I choose all of the above.

TV News Love Affair

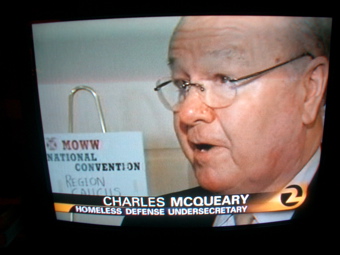

Let’s see: There’s a guy named Charles McQueary (Dr. Charles E. McQueary to you, thanks very much) who is undersecretary for science and technology at the Department of Homeland Security. So, given 5 or 10 minutes with those facts and a computer keyboard, how wrong could you get that if someone asked you to type his name and affiliation? Whatever your answer is, someone just topped you.

“Homeless Defense Undersecretary.” It’s about time.

Plainclothes Torturers

Excellent story this week in The Legal Times (subscription required) about newly declassified memos by military lawyers on the subject of stretching the legal definition of torture to allow more pressure to be put on our Global War on Terrorism prisoners. Civilian lawyers in the Justice Department (including a faculty member at my current workplace, Boalt Hall) advised our commander-in-chief he was standing on firm legal ground in allowing the military to take the gloves off.

How did the civilians’ counterparts in the armed forces — the judge advocates general — feel about expanding the definition of torture to allow more rough stuff and, presumably, get more actionable intelligence (Interrogator: “How does that feel?” Prisoner: “Aiyee! That really hurts!” Interrogator: “Captain, he says it hurts.”)?

In a word, they were against. According to The Legal Times story:

“… The military lawyers predicted that adopting more aggressive interrogation techniques to fight the war on terror would undermine America’s relationships with allies, hurt the reputation of the military, and possibly put U.S. troops in harm’s way. …

“… ‘Will the American people find we have missed the forest for the trees by condoning practices that, while technically legal, are inconsistent with our most fundamental values? How would such perceptions affect our ability to prosecute the Global War on Terrorism?’ wrote Rear Adm. Michael Lohr, then-judge advocate general of the Navy.

“The new documents reveal deep disagreement between top uniformed lawyers in the Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps and the administration’s civilian attorneys at the Pentagon and the Justice Department. The JAGs’ memos blast legal positions taken by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel and point to a secret memo from OLC lawyers that appears to have given the green light for U.S. troops to use interrogation

tactics in violation of military law.”

In Iraq

Word, first of all that 14 Marines were killed by a bomb in a place called Haditha. Six more were killed there the day before yesterday. So far, 22 U.S. soldiers have died in Iraq in the first three days of August.

Then there’s this: Steven Vincent, a freelance writer and blogger who had an op-ed piece in this past Sunday’s New York Times describing Basra’s police force and its growing allegiance to religious parties rather than the national government (or citizens), has been killed. He and his interpreter were kidnapped and shot, and the thinking is that he was assassinated because of his recent reporting. I haven’t read a lot of his stuff — his blog, occasionally, but not his Iraq book, “In the Red Zone” — but he struck me as a meticulously honest observer who was trying to look at the war in terms of the people we say we’re trying to help. Someone capable of seeing what is at stake for ordinary citizens in this struggle and the big gap between our declared ideals and goals and our execution. For instance, one of his last posts, “The Naive American.”

[Later: The New York Times did a nice short profile on Vincent. Among other things, turns out he was a Bay Area kid who went to Cal.]

‘The Victim and the Killer’

What I think is a great piece of reporting from Salon.com’s correspondent in Baghdad: The story (subscription required) of how a U.S. Army sniper killed Yasser Salihee, an Iraqi doctor working as a journalist for the Knight-Ridder News Service. Salon’s reporter, Phillip Robertson, had gotten to know Salihee and his family and decided to find the soldier who killed his friend and find out his version of what happened. Since our military maintains a strict and nearly complete silence about the civilian casualties it has inflicted in Iraq, and since it couldn’t be expected to cooperate with a journalistic investigation into Salihee’s death, Robertson took it upon himself to see if he could find the American unit involved and get embedded with it. He did it, and eventually met the unit’s sniper, identified only as “Joe,” who showed him pictures he had stored on a laptop of his tour of duty in Iraq.

“Then he brought up a photograph of a white Daewoo Espero sedan on a Baghdad street. The sedan had a single bullet hole in the driver’s side of the windshield. Behind the wheel there was a lifeless man, slumped in the seat with a shattered skull and a torrent of blood staining his shirt. The image carried a sudden shock of recognition and despair. The dead man behind the wheel of the car was my friend and colleague, Yasser Salihee.

“The sniper lowered his voice when he talked about the pictures of the car and the man inside it. His self-assured manner disappeared and he became nervous. ‘Here is one of ours. I really hope he was a bad guy. Do you know anything about him?’ Then he said, ‘See, I don’t know if I should be talking about this.’

” ‘Did you fire the shot that killed him?’ I asked.

” ‘I don’t know.’

“Joe said that it was true that he fired the shot through the Espero’s windshield, but he wasn’t positive if it was the lethal shot. There was no doubt that it was, but Joe seemed to be genuinely uncertain about it. It was clear that he did not want it to be true.”

I didn’t hear about it or read about it when Salihee was killed. After reading Robertson’s piece, I went looking and found a couple of tributes to him from colleagues: One from the Knight Ridder bureau chief in Baghdad, another from an NPR reporter for whom Salihee served as translator.

An awful irony: Reading about Salihee, he is just the kind of person one might hope could flourish in a land rid of dictatorship and fear, by all accounts a dazzlingly intelligent, giving, brave and daring soul. Yet his life was consumed by what we’ve set loose in Iraq. Among his wife’s comments, a few weeks after the shooting: “I want the Americans to go back to America, but I know they won’t go.”

The Wistfulness of Victory

Lance Armstrong just did what everyone who followed the Tour de France this year saw he would do: He won for the seventh time in a row. Now the race is over and he’s going into retirement. Which makes me feel lost on a couple of counts.

First: No more Tour. For the last three weeks — as for the past several years during Tour time — we’ve gotten up every morning and stumbled straight to the TV to turn on OLN’s live race coverage. I know I’ve whined about the incumbent announcers (it’s only a matter of time before someone gives Phil Liggett the Phil Rizzutto treatment and turns transcripts of his play-by-play into a book of “poetry. No, wait: Someone already has), but the anticipation of the unknown drama to unfold in the next morning’s stage has been wonderful. Would we wake up to a big breakaway? To Lance finally collapsing under relentless attack or having the Tour-ending mishap he always managed to avoid? (No way.) With the tube on, I’d fire up my laptop and keep track of the time gaps from the official Tour site. Every day: a coffee-powered multimedia frenzy. Now, it’ll back to the sports page and box scores when I get up (hey, the serious stuff can wait till I’m really awake).

Second: No more Lance. Paddling free of the hype-and-glitz whirlpool for a second — the cancer miracle, the celebrity girlfriend and all the rest — as an athlete the guy is really in a class by himself not just in cycling but in all sports. It’s astounding: his ability to plan and train the way he has all this time, and the combination of strength, guts and genius to perform when the moment demands it and resist the daily efforts of scores of people who have dedicated themselves to beating you. That has been thrilling to watch year in and year out; and — I probably have lots of company — I’m just a little sad to see it come to an end.

A Stillness in Iraq

It’s been quiet lately in Iraq, what with last week’s baseball All-Star Game, the Karl Rove Affair, the coming-party for our next Supreme Court guy, and the new Suzanne Somers show on Broadway.

Every once in a while you hear something, though. Maybe it’s a suicide bomber blowing up a gasoline tanker, immolating himself and scores of others. Or the raucous debate surrounding the birth of Iraq’s new democracy, complete with reduced constitutional rights for non-men. Or the insistent thump of improvised explosive devices and car bombs and other detonations (the “coalition” toll this month: 28 dead). Or the nearly inaudible sound of our future mortgaged to war (price tag for our crusade on evil-doers so far: $313 billion, and get ready for much, much more). Or the utter silence of the 24,865 Iraqi civilians who have died in the war.

Quiet week.