A slightly blurry, low-light, hand-held shot of a black-crowned night heron at the Clay Street ferry dock in Oakland. We’ve been seeing a couple of night herons hanging around the dock for the last several months. Lots of fish in the water right now–anchovies or some kind of bay smelt, we think–but we haven’t seen them go for fish. (What do they eat? Just about anything, according to one account: “The diet of the Black-crowned Night Heron depends on what is available, and may include algae, fishes, leeches, earthworms, insects, crayfish, mussels, squid, amphibians, small rodents, plant materials, garbage and organic refuse at landfills. They have been seen taking baby ducklings and other baby water birds. The night heron prefers shallow water when fishing and catches its prey within its bill instead of stabbing it. Herons will sometimes attract prey by the rapidly opening and closing the beak in the water to create a disturbance that attracts its prey. This technique is known as bill vibrating.”)

Web Billiards: Music Video-Skydive History Edition

A couple weeks ago, I happened across a nice time lapse of San Francisco scenes titled "The City." This is it:

The City from WTK Photography on Vimeo.

I duly shared the above via some social media platform or another. One of the things I really liked about the video is the music that accompanies it, "Dayvan Cowboy" by Boards of Canada. I didn't know from BoC, but I would characterize this as a jangly folk-rocky indie-esque electro-introspective piece.

About the same time, I got involved in a discussion about high-altitude parachute jumps. I remembered hearing or reading that sometime in the 1950s or '60s, someone had jumped from above 100,000 feet and that someone was planning to try to improve on that record. One thing always linking to another as it does out here, I found the man who made the famous skydive was Joe Kittinger, who was involved in Project Excelsior, a research program designed to develop high-altitude escape systems for the first astronauts. On August 16, 1960, he rode a balloon-lifted gondola to 102,800 feet–nearly 20 miles–above the New Mexico desert, then stepped off into the void and commenced a descent that lasted more than 13 minutes. He reached a top speed of 614 mph on the way down.

I promptly went on to other things, but the Boards of Canada music was stuck in my head. In looking for it online a couple days ago, I found an "official" video for "Dayvan Cowboy." The first segment of the video features Kittinger's Project Excelsior mission. Here:

I could hardly stop there. I figured there must be more extensive video of Kittinger's flight out there. Well, there is plenty, including several musical tributes to the flight (just Google "Joseph Kittinger" and "music"). Here's one that combines snippets of the flight video with a musical number ("Colonel Joe," by Alphaspin).

And here's one more, with a different soundtrack ("GW," by Pelican), that tech media guy Tim O'Reilly references in a blog post from a few years ago:

Coming Attractions: Autumn Rain

There it is: our first storm of what we’d like to call our rainy season (the live version of the image is here). The National Weather Service has been advertising this as a “rather weak” system that won’t drop much rain here. Maybe so, but the radar image–which doesn’t always depict what’s out there in the atmosphere–seems to indicate some moderate to heavy precipitation off the coast. We’ll see in the next few hours.

A Falcon’s Journey

Thanks to Marie, who posted the link:

Thanks to Marie, who posted the link:

The online diversion of the day is the Falcon Research Group, an independent raptor study center in Washington state. The group has satellite-tagged and tracked peregrine falcons that migrate over very long distances. Right now, they’re watching a falcon they’ve named Island Girl, who is in the midst of a journey from Baffin Island, northeast of Hudson Bay, to southern Chile (here’s the map of the migration so far). She left Baffin Island on September 20 and last night apparently crossed Louisiana’s Gulf Coast. If she was a straight-line flyer, and she’s not, she would have covered 2,600 miles in 11 days. One of her stops this past week was apparently atop the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield.

The research group blogs the migration here: Southern Cross Peregine Project. The account of the bird’s journey, informed by both experience with her life history, peregrine biology, and GPS data from a mini-backpack the bird is carrying, is both fascinating and sort of gripping. For instance: This is the third season the project has tracked the bird south. One post notes she has begun the migration inside a 24-hour window on September 20-21 each time (her northward migrations are similarly precise, occurring around April 12). Of the challenges peregrines face as they cover a vast swath of territory, the blog says:

Peregrines (and other long distance migrant hawks) can make a living catching their prey over a wide range of habitats. They must be able to do so if they are migrationg across such varied territory as the Arctic tundra, the Canadian boreal forest, the farmlands of the Mid-West, cities large and small, the sub-tropical regions of Mexico, the tropics of Central and South America, the intense Atacama Desert and the pine forests of southern Chile.

They must be adaptable enough to survive in each of these situations. They must have a flexible approach to hunting in different situations. They must be able to recognize, hunt and catch new prey species (do peregrines eat toucans?) and avoid all of the ever-present mortality sources.

Are these “slow migrant” peregrines that we have discovered during this study taking their time so that they can become familiar with these habitats and how to hunt them? Are they “familiarizing” themselves with their migratory route and what they can find there? Is this advantageous to them?

The complexity of peregrine migratory behavior is both deeply impressive and humbling. What a remarkable organism to fit into all of this and flourish.

Where’s Island Girl now? When last heard from, she was headed out over the Gulf of Mexico southwest of New Orleans. As the blog notes, the falcon may “attempt to fly across the entire Gulf of Mexico. It has been done by other satellite tagged peregrines in the past. However, taking this route means committing to the very exposed crossing of 500 miles across open water to Yucatan. Some tagged raptors have disappeared on this crossing. … If Island Girl does go and if she has a good tail wind, she is capable of making it. Keep in mind that there are also a lot of oil platforms out there to rest on and we know that peregrines show up on them during the fall migration fairly frequently. There are also lots of ships in the Gulf so she may have assistance there if she gets into trouble with a headwind.”

Six thousand miles to home. Go, bird, go.

Ballpark

On the walk to the ferry tonight. When I have time, I like to walk by AT&T Park on the waterfront side. It’s always cool to see the stadium, something of a waterfront jewel, landfill be damned. One of the features along the water frontage is an arcade where you can see into the ballpark from field level–you’re essentially standing just behind the right fielder. During the season, fans are welcome to take in the game for free from that vantage point; your turn lasts three innings if it’s crowded, and it’s nearly always crowded.

I’ve always found something sweetly pleasing about a ballpark as it empties out after a game, and among the favorite games I ever attended were afternoon dates at Wrigley Field when you could drift down from the cheap seats after the last out and just sit and watch while the last players cleared the dugout and the grounds crew started its postgame rituals. There’s a way in which the field is still alive for me though the play has stopped. You can still see what happened out there, the traces of arcs, parabolas, curves, lines, vectors all nearly still visible. The physical qualities of that space–the color of the grass, its texture, the shadows on the field, the immense and unconquerable but somehow finite and intimate distance to the outfield walls–have a power of their own that speaks as you linger, a power independent of the action you’ve just taken in. (I don’t think the modern major leagues allow much loitering in their amusement complexes now, and the field never seems as close as it used to. On the occasions I have tried to just hang out, there’s no going down to the expensive seats after the game, and the general experience is one of being hustled out as if your $20 or $30 or $50 or $100 entitles you to just so much and whatever that is it’s been used up. Go on home now.)

A ballpark after the season ends is a different story. Melancholy, a place deserted by everyone and everything that gave it purpose. The spaces, those unfathomable distances, are voids. No arcs or parabolas there. Until that changes, which they say happens next year, if we wait.

Boreal Chauvinist Welcomes Fall

The autumnal equinox–I’m letting my boreal chauvinism show–is just an hour or so away (2:05 a.m. PDT, 0905 Coordinated Universal Time. Special treat if you’re up in these wee hours: a crescent moon rising (nearly) alongside Mars).

In other equinox news, an explanation of the equinox by way of a 2007 NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day.

And not strictly equinox-related, but too beautiful to pass by: NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day for today, which features the aurora borealis as viewed in northwestern Canada. If you like that image, there a lot more here.

Update: Well, the sun is up and it’s sure enough fall. I was looking for an apt seasonal quote, and this morning Kate pointed one out; something from John Muir, cited as an introductory quote in a book of Diane Ackerman essays, “Dawn Light”:

“This grand show is eternal. It is always sunrise somewhere; the dew is never all dried at once; a shower is forever falling; vapor is ever rising. Eternal sunrise, eternal sunset, eternal dawn and gloaming, on sea and continents and islands, each in its turn, as the round earth rolls.”

(The quote apparently comes from Muir’s journals, published as “John of the Mountains” in 1938.)

Texting Antietam

‘A Lone Grave, on Battle-Field of Antietam.’ (Photographer: Alexander Gardner. National Park Service: Historic Photos of Antietam battlefield. Click for larger image.)

Texts with my brother John this morning:

John: Anniversary of Antietam … just FYI.

Me: John, you’re just about the only person I know who’d be thinking about that.

John: Yeah…I looked at the date on my faithful iPhone and it jumped right out at me…It is a cool pleasant day here in the east and I reflected that some of those soldiers that day may have taken note of similar weather, never getting a chance to enjoy it…a melancholy thought. In any event, I am currently working on some glass (engraving) and am enjoying the weather as well..and remembering all those young men…149 years ago…

Me: It’s beautiful out here as well. And yes, a lot of life, and lives, were swept away that day.

If you’re not familiar with Antietam: Fought September 17, 1862, at Sharpsburg, Maryland, about 50 miles northwest of Washington. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, attempting its first invasion of the North, vs. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, crippled by indecisive generalship and intelligence by way of the founder of the Pinkerton Detective Agency that Lee’s army was far larger than it was. The most common description of the battle: The bloodiest single day of the Civil War. Here’s a brief summary of the aftermath from James McPherson’s “Battle Cry of Freedom:”

“Night fell on a scene of horror beyond imagining. Nearly 6,000 men lay dead or dying, and another 17,000 wounded groaned in agony or endured in silence. The casualties at Antietam numbered four times the total suffered by American soldiers at the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. More than twice as many Americans lost their lives in one day at Sharpsburg as fell in combat in the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American war combined.”

Today’s also Constitution Day. One of the foremost interpreters of the Constitution, long after the battle, was on the field at Antietam. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was a captain in a Massachusetts regiment largely recruited at Harvard. He was shot through the neck early in the battle. Here’s an account of Holmes’s battle, from “Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: Law and the Inner Self,” by G. Edward White:

“On the morning of September 17 the Twentieth Regiment, designated as a reserve unit, was ordered up so far toward the front of Union lines that, as Holmes put it many years later, ‘we could have touched … the front line … with our bayonets.’ When the fighting began, ‘the enemy broke through on our left,’ and the Regiment, instead of being able to repel them, was ‘surrounded with the front,’ and an order to retreat was quickly given. Holmes remembered ‘chuckling to myself as I was leaving the field,’ since at Ball’s Bluff Harper’s Weekly had made much of the fact that he had been shot ‘in the breast, not in the back.’ This time he was ‘bolting as fast as I can … not so good for the newspapers.’ As he was retreating he was hit in the back of the neck, the ball ‘passing straight through the central seam of coat & waistcoat collar coming out toward the front on the left hand side.’ “

An officer managed to secure basic care for Holmes in a private home a few miles from the battlefield, then sent a telegram to Holmes’s family in Massachusetts. His father, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., was a doctor and one of the North’s leading literary names, and wrote an account of what happened next, “My Hunt After ‘The Captain’ ” for The Atlantic:

In the dead of the night which closed upon the bloody field of Antietam, my household was startled from its slumbers by the loud summons of a telegraphic messenger. The air had been heavy all day with rumors of battle, and thousands and tens of thousands had walked the streets with throbbing hearts, in dread anticipation of the tidings any hour might bring.

We rose hastily, and presently the messenger was admitted. I took the envelope from his hand, opened it, and read:

HAGERSTOWN 17th

To__________ H ______

Capt H______ wounded shot through the neck thought not mortal at KeedysvilleWILLIAM G. LEDUC

Through the neck,–no bullet left in wound. Windpipe, food-pipe, carotid, jugular, half a dozen smaller, but still formidable vessels, a great braid of nerves, each as big as a lamp-wick, spinal cord,–ought to kill at once, if at all. Thought not mortal, or not thought mortal,–which was it? The first; that is better than the second would be.–“Keedysville, a post-office, Washington Co., Maryland.” Leduc? Leduc? Don’t remember that name. The boy is waiting for his money. A dollar and thirteen cents. Has nobody got thirteen cents?

The elder Holmes decided to go find his wounded son and got on a train the next day. Holmes Jr. had already been sent on by the time his father got to the town named in the telegram; his father continued the search, but not before visiting the scene of the battle:

“We stopped the wagon, and, getting out, began to look around us. … A long ridge of fresh gravel rose before us. A board stuck up in front of it bore this inscription, the first part of which was, I believe, not correct: ‘The Rebel General Anderson and 80 Rebels are buried in this hole.’ Other smaller ridges were marked with the number of dead lying under them. The whole ground was strewed with fragments of clothing, haversacks, canteens, cap-boxes, bullets, cartridge-boxes, cartridges, scraps of paper, portions of bread and meat. I saw two soldiers’ caps that looked as though their owners had been shot through the head. In several places I noticed dark red patches where a pool of blood had curdled and caked, as some poor fellow poured his life out on the sod. I then wandered about in the cornfield. It surprised me to notice, that, though there was every mark of hard fighting having taken place here, the Indian corn was not generally trodden down. … At the edge of this cornfield lay a gray horse, said to have belonged to a Rebel colonel, who was killed near the same place. Not far off were two dead artillery horses in their harness. Another had been attended to by a burying-party, who had thrown some earth over him but his last bed-clothes were too short, and his legs stuck out stark and stiff from beneath the gravel coverlet. … There was a shallow trench before we came to the cornfield, too narrow for a road, as I should think, too elevated for a water-course, and which seemed to have been used as a rifle-pit. At any rate, there had been hard fighting in and about it. … The opposing tides of battle must have blended their waves at this point, for portions of gray uniform were mingled with the ‘garments rolled in blood‘ torn from our own dead and wounded soldiers.”

The National Park Service site for the Antietam National Battlefield includes an album of 30 images taken by photographer Alexander Gardner immediately after the fighting and now in the collection of the Library of Congress (the NPS site is the source of the images here). Beyond their blunt depiction of the slaughter’s aftermath, they carry a unique historical weight that Drew Gilpin Faust summarizes in “This Republic of Suffering:”

“For the first time civilians directly confronted the reality of battlefield death rendered by the new art of photography. They found themselves transfixed by the paradoxically lifelike renderings of the slain of Antietam that Mathew Brady exhibited in his studio on Broadway.”

Faust goes on to quote an October 20, 1862, article in The New York Times that discussed the impact of the photographs. Its acid tone is remarkable. “The living that throng Broadway care little perhaps for the Dead at Antietam,” the unsigned piece begins, “but we fancy they would jostle less carelessly down the great thoroughfare, saunter less at their ease, were a few dripping bodies, fresh from the field, laid along the pavement.” Eventually the writer takes us inside Brady’s studio:

“Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it. At the door of his gallery hangs a little placard, ‘The Dead of Antietam.’ Crowds of people are constantly going up the stairs; follow them, and you find them bending over photographic views of that fearful battle-field, taken immediately after the action. … [T]here is a terrible fascination … that draws one near these pictures, and makes him loth to leave them. You will see hushed, reverend groups standing around these weird copies of carnage, bending down to look in the pale faces of the dead, chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes. It seems somewhat singular that the same sun that looked down on the faces of the slain, blistering them, blotting out from the bodies all semblance to humanity, and hastening corruption, should have thus caught their features upon canvas, and given them perpetuity for ever. But so it is.”

‘View of Ditch on right wing, which had been used as a rifle-pit by the Confederates, at the Battle of Antietam.’ (Photographer: Alexander Gardner. National Park Service: Historic Photos of Antietam battlefield. Click for larger image.)

Paper

Revised, Sept. 11, 2019.

We all carry some part of 9/11 with us.

There’s raw memory, of course: what we recall about where we were, our experiences that day, the devastation as we saw what unfolded.

And there’s something I’ll call “considered memory”: how we see that experience through the prism of all we’ve lived through, both privately as individuals and as a nation, since that date.

For me, honestly, I’m still puzzling over it. I’ve had an absorbing interest in our history for almost as long as I can remember, since a kids’ Civil War book was put into my hands and I pronounced Potomac as “POT-oh-mack.”

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to understand that one attraction of history, especially the history of war, of conflict, of tragedy, is the recounting of the battle and the exploit in much the same way the epic singers of old traveled from court to court to relate “The Iliad.” The battle and the exploit, the courage or failure of courage, themselves become the moral of the tale.

Often the recounting goes no further. The Light Brigade is forever charging the guns, always fulfilling a tragic destiny. But what then? What happens after Pickett’s Charge is broken, after Appomattox, after the arms are stacked and the banners furled? What happens when we move beyond the sepia-tinted memories, the strains of elegiac strings, into the life that follows the battle?

The “what then?” is what I’ve started to think more about lately. To the extent I’m thinking about what Sept. 11 means, that’s what’s on my mind.

***

My brother John and his family lived in Brooklyn, a little more than 2 miles southeast of the World Trade Center, on Sept. 11, 2001. The attacks and their aftermath, things heard and seen, were intimate and immediate.

John’s wife, Dawn, was just emerging from the subway when a jet screamed low overhead and vanished, followed by the sound of an explosion. Looking south from the corner, she could see the World Trade Center’s North Tower had been hit.

John was at work in Brooklyn and watched from a rooftop as a second jet roared across the harbor and struck the South Tower. On the street below, New York Fire Department units sped toward the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel to respond to the disaster across the river.

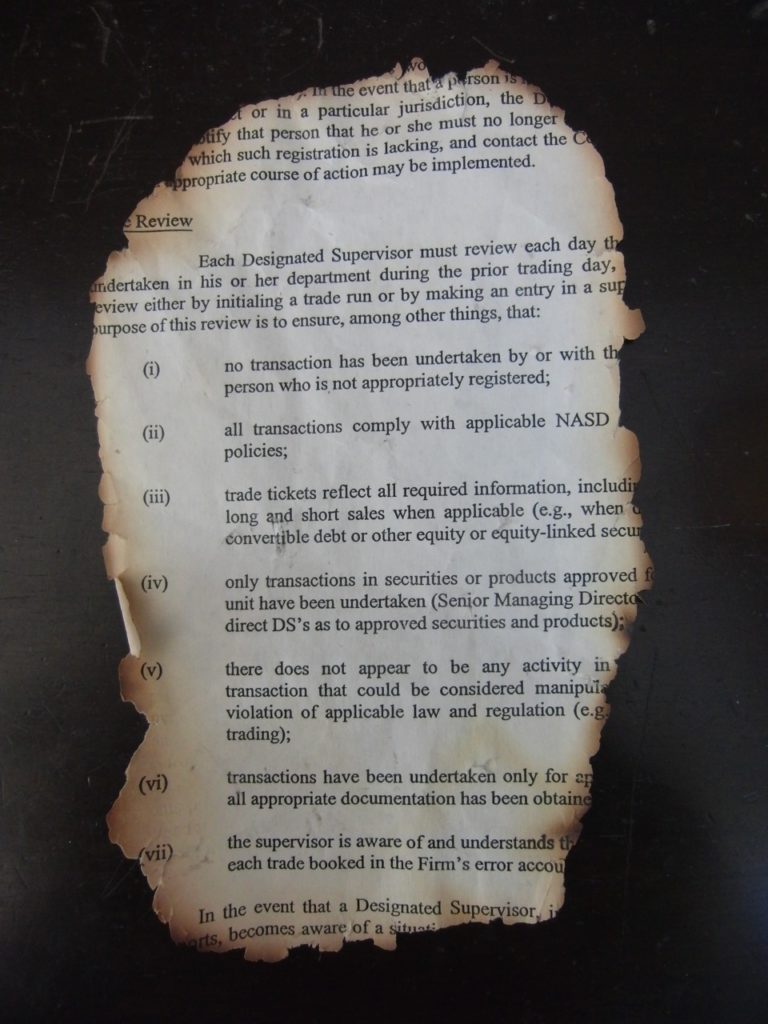

John and Dawn’s neighborhood was downwind from the towers, and the blizzard of dust and paper unleashed when the buildings collapsed scattered scraps of paper everywhere. John told me later he would go around and pick up bagsful of litter that appeared to be from the towers. At one point, he sent me a small bag with a few of the items he’d found.

I puzzle over these fragments. They’re mundane: part of a financial firm’s rules for handling trades. A blank visitor log for a government office. Design drawings for airport terminal signage. A page from a desk calendar (the date happens to be my birthday).

There’s not a human mark on those scraps of paper. But they were handled by someone, somewhere, in a place we all saw destroyed. Touching them is like touching that place, touching that destruction, touching those who were lost.

***

So what’s the “what then?” in our 9/11 story? One could say it’s too early to tell.

But is anyone, anywhere really satisfied with any of the outcomes we know about? Our ceaseless wars? Our embrace of assassination and torture as a means of making “the homeland” secure? The cost to our liberties through the adoption of such measures?

The climax of “The Odyssey” is the hero’s return home after an epic of misfortune. But it’s more than a homecoming – it’s occasion for revenge. Odysseus, his son and their allies slaughter the young men who have been courting his wife, Penelope, and despoiling his estate. But that’s not the end of it. The fathers and brothers of the murdered suitors are bent on vengeance themselves.

The goddess Athena, who has engineered Odysseus’s return and his attack on the suitors, doesn’t like what she sees brewing: an endless cycle of retaliation. She appeals to Zeus, her father, to stop it. He points out that she’s distressed about her own handiwork, but says she’s free to intervene.

“Do as your heart desires,” he says. “But let me tell you how it should be done:

“Now that royal Odysseus has taken his revenge,

let both sides seal their pacts that he shall reign for life,

and let us purge their memories of the bloody slaughter

of their brothers and their sons. Let them be friends,

devoted as in the old days. Let peace and wealth

come cresting through the land.”

Would that it were so simple, or that we had gods so direct about pulling the strings. What 9/11 means for me, more than anything, is that there is no going back to what was before.

***

I went up in the World Trade Center twice. Once during a visit in 1985, once in August 2001, about four weeks before the attacks. I was with my son, Thom, and John and his son, Sean. We were on top of the South Tower.

It was a high place with a view and some history: We talked about the guy who had climbed the tower, and the guy who had walked a high-wire between the towers.

Watching an airliner fly north over the Hudson, John recalled the story of an airline pilot who had, on a clear day, gotten off his flight path and flown his plane far too close to the towers and apparently lost his job over it. In fact, that conversation was the first thing that came to mind the morning of 9/11 when, standing in a San Francisco newsroom just before 6 a.m., I saw the first pictures of the North Tower after it had been hit.

One other memory.

I was at JFK airport, on a jet taxiing out to take off. The sun was just rising. I looked out my window and, far to the west, the towers caught that first stunning golden light. I still see them shining.

Chicagoland Cemetery Report

On the eve of Dadfest (his ninetieth birthday, tomorrow), I took him to a local barber for some tonsorial attention. With that seen to, we stopped at the Steak ‘n’ Shake drive-through, then headed north to intercept Sheridan Road on the North Shore. We wound up in Lake Forest, where I happened to notice a sign for a beachfront park: “Parking Entrance for Lake Forest Residents.” OK–I wanted to see what being a Lake Forest resident gets you.

I wound down a steep drive to a beautiful little beach and well-kept park and parking lot that was guarded by a young guy lounging in a lawn chair. I signaled to him we were just going to turn around and did that. I stopped and asked the guy about beach parking access. Yes, it was for residents, who could park for free. Could non-residents park there? Well, only if they have a season permit. How much is that? About $900 (and looking into things a little further, a season parking permit at the southern end of the park is $1,400). The city’s brochure on all this explains that non-residents are welcome to park at the train station in downtown Lake Forest, a mile west as the crow flies (and they’re welcome to use the beach, too, but need to pay ten bucks a head on weekends and holiday). And one last welcoming touch: Anyone who parks along any street east of Sheridan Road–close to the beach, in other words–will be ticketed and fined $125.

My beach curiosity satisfied, we continued on. Down a street marked with a “No Outlet” sign, I saw a massive gate and decided we needed to investigate that, too. It was the Lake Forest Cemetery. It’s well-tended, and many of the graves–for instance, that of 19th century wholesaling titan J.V. Farwell–are lavish.

The site above grabbed my attention. It’s the resting place of Frederick Glade Wacker, son of the man for whom Chicago’s Wacker Drive is named, and his wife, Grace Jennings Wacker–the latter once a Brooklyn Heights debutante. Their marriage in 1912 got some serious New York attention–both in The New York Times (here: New York Times wedding announcement) and in more detail in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (here: Brooklyn Daily Eagle). Mr. Wacker didn’t reach 60. Mrs. Wacker died in the 1980s at the great age of 95, if her headstone is to be believed.

The Wackers did have children. There was a Frederick Jr., a businessman and motor sports enthusiast who died in 1998. HIs obituary in the Chicago Tribune lists three children and a grandson as survivors. Not mentioned is a brother, Charles Wacker III, who happened to be out of the country when Frederick Jr. died. Perhaps he went unlisted because of the circumstances of his absence.

In 1993, Charles Wacker III, who had made a name for himself as an owner and breeder of thoroughbred racehorses, was indicted on 16 counts related to an alleged tax-evasion scheme. Here’s how the Trib summarized the case:

“In its 50-plus-page indictment, the government alleged that the 72-year-old Wacker spent a decade creating a network of dummy corporations and hidden bank accounts from North Chicago to Hong Kong to shield himself from the IRS. Federal officials also alleged that Wacker defrauded his mother, Grace Jennings Wacker, and her estate of more than $500,000.

The story notes that the government accused Wacker of running his shell game to dodge $5 million in federal taxes and–how times have changed–says that it was the most massive personal tax evasion case in the history of the federal Northern District of Illinois. Other news accounts noted that he didn’t show for his first court appearance in Chicago. He was in England, where he ran his horse operation. His lawyer told the judge he was too ill to travel.

You see something sensational like that, and you want to know more. Whatever happened to CWIII? Is he languishing in a federal penitentiary somewhere, a la Bernie Madoff? Did he beat the rap?

Well, I couldn’t find a single news source that reported the denouement of the Charles Wacker III tax-fraud saga after the accounts of that first hearing. But I did dig up something from an online federal court file.

In 2002, the U.S. attorney for the district went to court to dismiss all charges. Why? Well, Charles was a fugitive, and prosecutors said he couldn’t be found. Also, the witnesses–Wacker’s accountant and Frederick Jr.–were deceased. And at the time the charges were dismissed. Wacker was 80. The Department of Justice motion (here: Wacker dismissal) doesn’t expand on that last fact except to imply, “What’s the point of going after him now?”

Charles Wacker III will be 90 on October 21, if he’s still living. I can’t find an obit for him. But I do find mentions as late as 2007, when he would have been 85 or 86, that he was still active in the horse-racing world.

Heat Blog: Hot in Chicago

When we were in Chicago a few weeks ago, it was hot and humid virtually the entire week or so we were here. Temperatures up to the mid-90s and some real sweaty 80 to 90 percent humidity days that persisted after the heat eased a bit. At the tail end of our stay, the weather broke and highs fell into the 70s. I’m told they stayed that way until my return today, when the high downtown hit 97. Right now, it’s getting close to 1 a.m. in Chicago. The temperature: 86 degrees at O’Hare, 87 at Midway. That’s extraordinary for the middle of the night. Tomorrow’s forecast: the upper 90s again.

(Yes: I’m aware that people in Texas and the southern Plains have been going through about three months of this without a break. And yes: I enjoy our effete fog-bank summers in the Bay Area, which sometimes seem cool enough to keep your viognier nicely chilled without benefit of a fridge.)

Chicago meteorologist Tom Skilling breaks down the late-season heat wave in a post on the Chicago Weather Center super-blog:

The heat is on;Chicago is headed into the hottest opening two days of any September in 58 years!

(That exclamation point lends a certain “War of the Worlds” air to the proceedings, I think. And 58 years seems like ancient history, harking back to the days of Demosthenes or Davy Crockett. But then I remembered my mom was about two months and counting into her pregnancy with your humble blogger.)

Tom says:

It’s not at all “typical” to see temperatures here this late in the season as hot as those being predicted over the next few days. Highs are to reach 94-degrees Thursday and 98-degrees Friday. A few of Friday’s hottest temperatures could reach or exceed 100-degrees.

Back-to-back 90-degree or higher temperatures last occurred on September’s two opening days three years ago in 2008. But you have to go back 58 years—to 1953—-to find readings on September 1 and 2 warmer than those in coming days. That’s the year September opened with two 101-degree highs on the 1st and 2nd.