Revised, Sept. 11, 2019.

We all carry some part of 9/11 with us.

There’s raw memory, of course: what we recall about where we were, our experiences that day, the devastation as we saw what unfolded.

And there’s something I’ll call “considered memory”: how we see that experience through the prism of all we’ve lived through, both privately as individuals and as a nation, since that date.

For me, honestly, I’m still puzzling over it. I’ve had an absorbing interest in our history for almost as long as I can remember, since a kids’ Civil War book was put into my hands and I pronounced Potomac as “POT-oh-mack.”

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to understand that one attraction of history, especially the history of war, of conflict, of tragedy, is the recounting of the battle and the exploit in much the same way the epic singers of old traveled from court to court to relate “The Iliad.” The battle and the exploit, the courage or failure of courage, themselves become the moral of the tale.

Often the recounting goes no further. The Light Brigade is forever charging the guns, always fulfilling a tragic destiny. But what then? What happens after Pickett’s Charge is broken, after Appomattox, after the arms are stacked and the banners furled? What happens when we move beyond the sepia-tinted memories, the strains of elegiac strings, into the life that follows the battle?

The “what then?” is what I’ve started to think more about lately. To the extent I’m thinking about what Sept. 11 means, that’s what’s on my mind.

***

My brother John and his family lived in Brooklyn, a little more than 2 miles southeast of the World Trade Center, on Sept. 11, 2001. The attacks and their aftermath, things heard and seen, were intimate and immediate.

John’s wife, Dawn, was just emerging from the subway when a jet screamed low overhead and vanished, followed by the sound of an explosion. Looking south from the corner, she could see the World Trade Center’s North Tower had been hit.

John was at work in Brooklyn and watched from a rooftop as a second jet roared across the harbor and struck the South Tower. On the street below, New York Fire Department units sped toward the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel to respond to the disaster across the river.

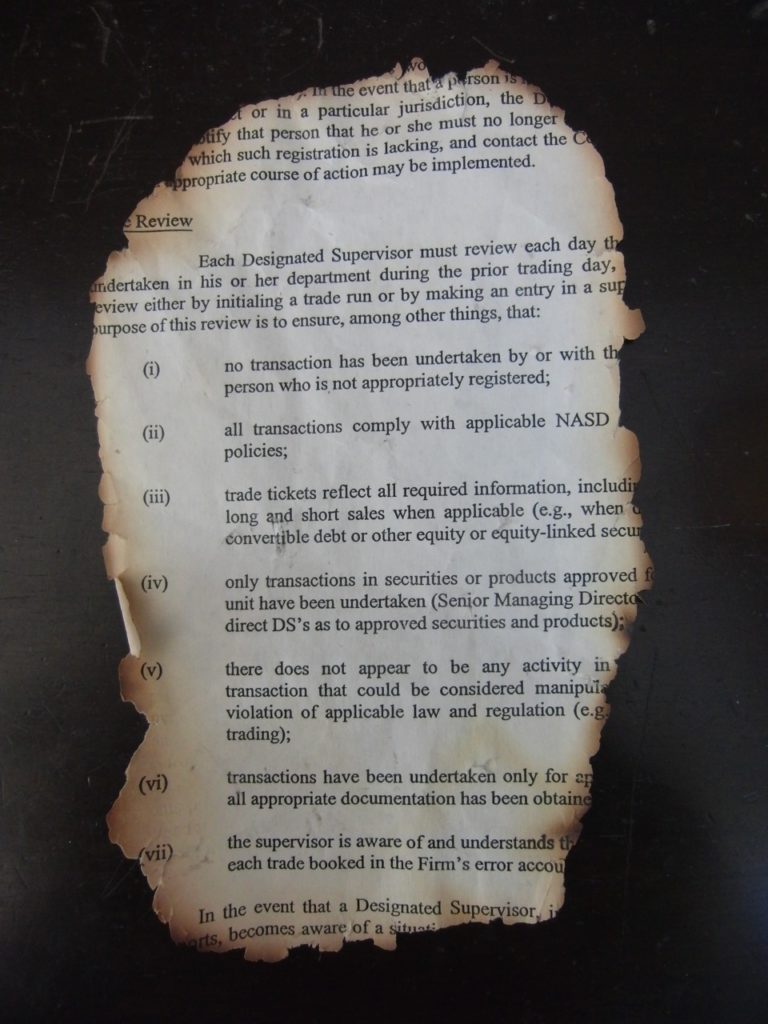

John and Dawn’s neighborhood was downwind from the towers, and the blizzard of dust and paper unleashed when the buildings collapsed scattered scraps of paper everywhere. John told me later he would go around and pick up bagsful of litter that appeared to be from the towers. At one point, he sent me a small bag with a few of the items he’d found.

I puzzle over these fragments. They’re mundane: part of a financial firm’s rules for handling trades. A blank visitor log for a government office. Design drawings for airport terminal signage. A page from a desk calendar (the date happens to be my birthday).

There’s not a human mark on those scraps of paper. But they were handled by someone, somewhere, in a place we all saw destroyed. Touching them is like touching that place, touching that destruction, touching those who were lost.

***

So what’s the “what then?” in our 9/11 story? One could say it’s too early to tell.

But is anyone, anywhere really satisfied with any of the outcomes we know about? Our ceaseless wars? Our embrace of assassination and torture as a means of making “the homeland” secure? The cost to our liberties through the adoption of such measures?

The climax of “The Odyssey” is the hero’s return home after an epic of misfortune. But it’s more than a homecoming – it’s occasion for revenge. Odysseus, his son and their allies slaughter the young men who have been courting his wife, Penelope, and despoiling his estate. But that’s not the end of it. The fathers and brothers of the murdered suitors are bent on vengeance themselves.

The goddess Athena, who has engineered Odysseus’s return and his attack on the suitors, doesn’t like what she sees brewing: an endless cycle of retaliation. She appeals to Zeus, her father, to stop it. He points out that she’s distressed about her own handiwork, but says she’s free to intervene.

“Do as your heart desires,” he says. “But let me tell you how it should be done:

“Now that royal Odysseus has taken his revenge,

let both sides seal their pacts that he shall reign for life,

and let us purge their memories of the bloody slaughter

of their brothers and their sons. Let them be friends,

devoted as in the old days. Let peace and wealth

come cresting through the land.”

Would that it were so simple, or that we had gods so direct about pulling the strings. What 9/11 means for me, more than anything, is that there is no going back to what was before.

***

I went up in the World Trade Center twice. Once during a visit in 1985, once in August 2001, about four weeks before the attacks. I was with my son, Thom, and John and his son, Sean. We were on top of the South Tower.

It was a high place with a view and some history: We talked about the guy who had climbed the tower, and the guy who had walked a high-wire between the towers.

Watching an airliner fly north over the Hudson, John recalled the story of an airline pilot who had, on a clear day, gotten off his flight path and flown his plane far too close to the towers and apparently lost his job over it. In fact, that conversation was the first thing that came to mind the morning of 9/11 when, standing in a San Francisco newsroom just before 6 a.m., I saw the first pictures of the North Tower after it had been hit.

One other memory.

I was at JFK airport, on a jet taxiing out to take off. The sun was just rising. I looked out my window and, far to the west, the towers caught that first stunning golden light. I still see them shining.

Wow, I forgot about that stuff. I have some this stuff somewhere around here. I also have a couple of photos from the August trip to the Trade Center. Maybe I can scan them for you.

Hey, John: I’ve got a couple of those snapshots around, too — didn’t look for them today, though. Would like to see the shots if you find them.