Sunday evening at Rose and Henry streets, North Berkeley, on our way back from a walk into the hills. The weather service describes these as “high clouds streaming over the forecast area … associated with a low pressure system” over the Pacific seven or eight hundred miles to our northwest and headed our way. A wet week in April–not unusual but definitely welcome given our drier-than-normal winter.

Friday Night Crane

A crane at the Port of Oakland’s Charles P. Howard Terminal, just west of the Jack London Square Ferry dock. We had just gotten off the boat after a roundtrip to San Francisco. I didn’t expect to capture Orion, but there it (or he) is at the upper left. The bright star to the right is Venus, with the Pleiades dimly visible in the background. At bottom right is the stern of the Potomac, FDR’s presidential yacht, which fetched up in the port after a colorful history involving Elvis Presley, drug runners, and the U.S. Customs Service.

A.M. Window

On Capp Shotwell Street, an alley-like little street that runs down the east side of the Mission district in San Francisco. There’s one block, between 16th and 17th streets, that always has some visual surprise despite the superficially bland surroundings (a health clinic and a few two-flat buildings on one side of the street and what looks like a garage or maintenance building on the other side). Up there, that’s a window of the garage, as seen yesterday morning.

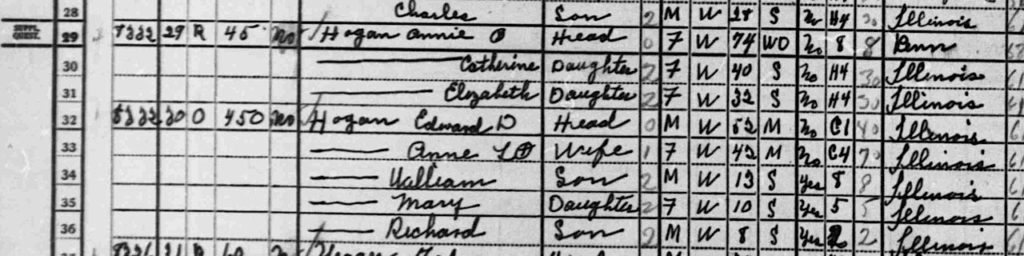

1940 Census: The Enumeration

The west side of the 8300 block of S. May Street, Chicago, in the 1940 census (click for a larger version.)

A while back, it occurred to me I’d better start recording the basics of some of the “how we’re related” family stories I’d heard for a long time from my mom and dad. Not that the stories are terribly complex in my immediate family. My dad is an only child (translation: I have no first cousins on his side of the family). My mom was the only girl among six children; of her five brothers, four lived to adulthood, and all of them became Roman Catholic priests (translation: no first cousins, or rumors of first cousins, on her side of the family). A generation back, though, and there were lots of kids. Both of my grandmothers came from big families, and each of my grandfathers have four or five adult siblings. That’s enough to create some complicated relationships, and as my parents’ generation has passed on–my mom died in 2003, the last of her siblings followed just a few months later, and at 90 my dad has likely outlived all his first cousins–there’s no one left to explain how all those family members you happen across in a cemetery or family tree relate to each other.

So, I’ve become mildly proficient at sorting through census records, and when the 1940 census came out this week, I was interested in tracking down family members.

But the 1940 data has a twist: There’s no name index. Meaning that you can’t find your relatives by going to some nicely organized website, plug a name in to a search blank, and find them in the census (that will come later, after the Mormon-organized army of volunteer transcribers does its work). Instead, you need to know where your family lived–and the more precise the idea you have, the better. In the case of some of our Chicago family, I know my mom’s and dad’s childhood addresses off the top of my head. Those are places we visited as kids and have been back to, just to take a look at them, as adults. At some point over the last decade or so, I also figured out my mom’s mom’s parents exact address on the South Side.

The newly released records are organized by Census Bureau Enumeration Districts: the patches of territory assigned to the 120,000 census takers who recorded the 1940 population. An enumerator was supposed to be able to cover an urban district in two weeks, a rural one in four weeks. For city areas, that was at least 1,000 people, and an enumerator might fill out forty pages of census schedules (forty people to a page) while visiting every domicile in the district.

As I said, there’s no way of digging individual names out of the millions of pages of census records released this week. But through the work and technological savvy of a brilliant San Francisco genealogist named Steve Morse, you can find people if you have a reasonably precise idea of where they lived. Morse created a site called the Unified 1940 Census ED Finder, which is the front end for a database that apparently contains information on every block of every street in every U.S. community. If you know someone lived at West 83rd Street and South Racine Avenue in Chicago, Morse’s site allows you to plug that information in, along with other cross streets, and discover the enumeration district where your person lived.

In 1940, my mom’s family lived in the 8300 block of South May Street, a block over from 83rd and Racine. Morse’s site shows that was Chicago Enumeration District 103-2222. The enumerator, Bezzie K. Roy, filled out thirty-six schedule pages in visiting the district’s households. You never know when you start looking through those thirty-six pages whether you’ll find the people you’re looking for on the first page or the last–I think you’re at the whim of the enumerator, though maybe there was a method to the job (for instance, start at the west edge of a district and move east, or something like that). In this case, Bezzie Roy visited my mom’s block on page three.

The family lived in a two-flat building. My mom, who was 10 when the census was taken, lived on the ground floor with her parents and four brothers. Her grandmother — her father’s mother — lived upstairs with two of her grown daughters (such a deal for my grandmother, living downstairs from her in-laws). There they are, eight lines at 8332 S. May Street. That in itself seems to be a mistake. My mom had identical twin brothers, Tom and Ed, who would have been 6 at this time and who are not listed here. It’s hard to imagine my grandmother, who was the one indicated as having supplied the information, not listing everyone in the family. Where are the twins?

The other thing I’m struck by in seeing this simple list of names is how much it doesn’t say. Edward D. Hogan, my mom’s father, had been diagnosed with lung cancer by this point and only had about 14 months to live. Eight months before this census record, my mom, Mary Hogan, had survived a drowning that killed John Hogan, one of her older brothers. A month after that, my mom’s grandfather, Tim Hogan, who lived upstairs, died. I’ve thought a lot about what it must have been like in their household at this time. But as you page through the records of this block and all the neighboring streets, it’s certain that other homes harbored stories that simply aren’t visible in this enumeration.

(Click the images for larger, readable versions).

Belfast Water

The local hole-in-the-wall liquor store, as seen on a late-birthday-night walk with The Dog.

Red, White, and Blue (and Green)

The city of Berkeley has planted new street trees around our neighborhood. We’ve seen a variety in the past, from scrubby, less-than-robust-looking Chinese pistaches, liquidambars, and this-one-with-rough-bark-that’s-quite-beautiful-in-the-autumn. There’s a stout-looking eastern oak across the street from us, right next door to a lot where the former residents planted a couple maples in the curb strip. The maples are OK, but since they’re growing into the power lines, they’ve had great big aggressive V’s pruned into their crowns.

The newer trees are maples, too. A dying camphor tree was removed from the curb strip next-door about six or seven years ago, I’m guessing, and a maple took its place. Our former neighbor took great care of the young tree (meaning it got plenty of water during our six-month annual drought), and it’s taken off–it’s already getting close to 15 or 18 feet high. It’s already pushing out its leaves (and a healthy crop of seeds, too, it looks like–not sure it’s done that before).

Local and Regional Weather, Part 2

The day began with rain, and with rain it ends. A sort of anemic late-season storm arrived before dawn and then parked. Even a weak little storm will get you wet when it decides not to move on. I can hear rain on the roof and running down the drainpipes. At the other end of the house, I can hear the TV weather guy talking about the rain continuing. I’m thankful for a dry space to sit and listen.

Local and Regional Weather

If you spend time on the National Weather Service sites, you’re familiar with their regional forecast maps, mosaics of color denoting advisories for floods (in different shades of green), winter storm watches and warnings (purple and pink), and red-flag alerts (an alarming scarlet). One “forecast advisory” I had never encountered on a weather map before: a child abduction emergency.

Wow. I get the whole amber alert movement, even though I have to admit that the ubiquitous bulletins to keep an eye out for certain cars always triggers a creepy sensation for me (it would be easy to use the alert network for other purposes, like looking out for subversives). I just wonder how useful weather mapping is for spreading the news about an apparent parent-abduction case. Maybe it’s very effective. It got my attention.

As to the son and father and mother involved in this incident: I hope it all ends well.

Birthday Celebration

It was raining hard last night when I left work, so instead of hiking over to the ferry as usual, I walked over to the 16th Street BART station, and rode downtown. I strolled across the rainswept plaza to the Ferry Building. Inside, I stopped to fiddle with some important matter on my phone. After a couple minutes, I was approached by someone and without looking knew I was about to get hit up for some change.

“Sir, it’s my birthday and I just need 50 cents so I can celebrate” was the gaff, delivered by a guy a little younger than me. He was wearing a black watch cap and sweatshirt and some other foul-weather gear and looked like he lived outside.

“What kind of celebration are you going to have for 50 cents?” I asked. Really. And I realized I probably did have 50 cents in my jeans pocket.

“Well, actually I could use any kind of change at all,” he said. I looked at the coins I’d dug out of my pocket–two quarters, a dime, a nickel. Then I thought about how much money I had on me. A coworker had needed to borrow twenty bucks earlier in the week and had just repaid me. I had another twenty in there, too, which I was going to use to buy our customary Friday night drinks–a beer for me, a white wine for Kate–on the boat.

What the hell, I thought. I took out my wallet, took out one of the twenties, and handed it to the guy. “Don’t celebrate too hard, I said.”

He thanked me, then looked down at the bill. And then he grabbed my hand and really thanked me. He had an urgent, almost shocked look in his eyes. “Take care of yourself,” I said. “It’s wet out there.” I thought: “Is it your birthday? Doesn’t matter. How much difference can that cash really make?”

If I’d really been thinking, I would have asked his name.

Till It’s Over Over There

U.S. Sergeant Is Said to Kill 16 Civilians in Afghanistan

PANJWAI, Afghanistan — Stalking from home to home, a United States Army sergeant methodically killed at least 16 civilians, 9 of them children, in a rural stretch of southern Afghanistan early on Sunday. …

You can be angry about this, or heartsick, or both. Most of us—and I emphatically include myself in that “us”—don’t give a thought to what’s happening over in Afghanistan, either to the Afghans or to the people we’ve sent to carry out a mission we no longer understand (and without understanding, it’s beyond me how there can be any real support). It’s true that a report of violence will interrupt the general silence over this war and momentarily attract some attention (“Burn any Korans lately? And how did that go for you?”).

We’ve had a copy of a literary magazine–The Sun– sitting amid the pile of papers on our dining room table the last couple of weeks. A friend gave it to us because she has a poem in the issue. By coincidence, I picked up The Sun after reading the story above. Leafing through it from back to front, I came across a page that featured portraits of two Marines in Afghanistan. There were two pictures of each Marine: on the left, a frame showing them in full combat gear; on the right, a frame of them with no gear.

There were six pages of portraits, twelve Marines, members of a platoon in the middle of a seven-month tour of duty in Helmand Province last year. A short essay by the journalist who took the pictures, Elliott D. Woods, summarized what had happened to the platoon during its first few months in the country:

“Four months into their seven-month tour, the mostly nineteen- and twenty-year-old marines at Patrol Base Fires in Sangin, Afghanistan, had seen enough violence to permanently line their boyish faces. Two of their platoon’s men had been killed by improvised explosive devices (IEDs), one of them blown literally in two. A half dozen had gone home without their legs, and others had suffered severe concussions or taken fragments of flying metal on their exposed faces and through the gaps n their Kevlar armor. By the time I arrived to photograph them in July 2011, First Platoon’s casualty rate was more than 50 percent.”

(You can find the photo essay, in three parts, on Woods’s site, Assignment Afghanistan, or at the Virginia Quarterly Review.)

Woods also has this to say about the setting of the Marines’ mission: “The district is so remote, so cut off from the Afghan government, that none of the farmers with whom I spoke knew the name of their country’s president. They could not name Helmand’s provincial governor either, or even their district council leader. They did not know what country the marines in their fields had come from, let alone why they were there. They did know that they were tired of living in a war zone. They were afraid of everyone, and that fear had driven hundreds of Sangin families to Kabul, where they were waiting out the war in filthy encampments on the city’s western outskirts.”

One other thing about Sangin: This is one of the places the British fought during their part of the Post-9/11 War. See the video below.