What does it mean when someone tells you, “You’re a blessing in disguise”?

70 MPH Dog

Sunday on Interstate 5, getting close to Red Bluff in the northern Sacramento Valley. You get used to seeing all sorts of interesting dog antics in moving vehicles. A neighbor is fond of driving around with his beagle on his lap, sticking its head out of the driver’s window for a better look at the passing scenery. Cute, I guess, but fundamentally dumb (why, for instance, should the dog get tangled up in the deploying airbag when the inevitable comes to pass? For now, we won’t discuss the merits, or lack of same, of taking pictures while driving; besides, I only took the picture above).

So here’s a little pickup truck moving at the I-5 speed limit, 70, with one very active passenger in the back. The dog’s ability to get his head out into the wind and keep his balance was pretty impressive. But again, it seemed fundamentally dumb on the driver’s part. Regardless of the dog’s agility, Newton’s laws (see “bodies in motion,” etc.) are in full force on the nation’s highways; it doesn’t seem like it would take much to separate dog from vehicle. Later, I wondered whether the loose dog in the back was breaking more recently announced (though perhaps less universal) laws.

California (and probably most other states) requires that dogs in pickups be cross-tethered or in a secured carrier so they don’t go tumbling into traffic. But the apparently pertinent passage of state law — California Vehicle Code Section 23117 — includes an interesting set of exceptions. Dogs don’t need to be secured if their owner is a farmer or rancher (or works on a farm or ranch) and they’re being transported on a road in a rural area or to and from a livestock auction; and they can be loose in the truck, apparently, if they’re being transported “for purposes associated with ranching or farming.”

Still. Seventy miles an hour on an interstate seems like a stretch. When we were passing the truck after the first picture was taken, we saw there was a second dog in the bed of the truck, too. But it had a more hunkered-down approach to highway travel.

I-5 Regular

Thom and I drove up to Eugene from Berkeley on Sunday (with his dorm-mate Sam, who rode up with us after getting stranded in the San Francisco airport on his way back to school from New York. A 500-mile trip, and a lot of the Oregon stretch that had been alien territory is becoming familiar: the four low summits between Grants Pass and Canyonville; the Seven Feathers Casino (free and not-too-awful coffee at the tribe-owned gas station and mini-mart), the two sharp mountainside turns at Myrtle Creek (they get your attention because the I-5 speed limit drops to 50 mph there). I’m starting to have a Eugene-trip routine: We drop Thom’s stuff off at his dorm, go to dinner, then I head back south. As when I made this trip in November, I got as far as Yreka (home of my favorite non-existent bakery) before my brain said, “Enough.” I got a room around midnight in the Best Western at the bottom of central Yreka exit ramp. A sign that I’m becoming an I-5 regular: The clerk recognized me.

Off again now to return to Berkeley. Stay tuned for pictures of 24-hour drive-thru coffee and the 70 mph dog.

Ride

Out of the house this morning at 7:30 to lead a ride from Berkeley up to Davis, near the western edge of the Central Valley. It’s 60 miles away by car; 100 miles by my zig-zagging cycling route. The unknown this morning was whether more than one or two other people would show up to ride; the uncertainty was occasioned by a good rain last night that had been forecast to last into the morning. But the weather had cleared by dawn, and I went over to the meeting place hoping maybe three or four or five people might show. Instead, 14 riders appeared, including two pairs on tandems. The roads were wet but the sky was mostly clear and the winds mild all day. Compared to many of the longer rides in this area, which feature lots of hill climbing, this route is mostly rolling. But even the constant up and down of mini-climbs can wear you down, and I was pretty tired when we finally rode east from the last small hill on the route into the flats of the valley (it really is that abrupt). Our goal was to get to Davis in time to get something to eat, then get on a 4:25 p.m. train back to Berkeley. No problem — we ate at a place across the street from the station, rode over and got tickets, waited 10 minutes for the train, quickly loaded the bikes (a large section of one car was devoted to bike racks), and had a fun ride back home as the sun set. Hard to beat.

Tragedy Stalks Berkeley Rat

OK — not tragedy. Deflation. With extreme prejudice.

The Berkeley Daily Planet has the story (purple prose no extra charge):

“A surreptitious stalker slashed the robust rodent outside Berkeley Honda at high noon Thursday, briefly deflating the colorful symbol of striking union members.

“…Teamster Jim O’Hara, who has been walking the picket line, said he had momentarily left the rat moments after noon Thursday to talk to colleague Dave Allen, who was picketing near the dealerships shop entrance.

“The two soon observed with alarm that the $3,000 rat had started to keel over.

“…On lifting up the sadly supine rodent, they discovered three long knife slashes in the critter’s belly, and O’Hara grabbed his camera to document the incident as his colleague called police.”

The story reports the rat — the $3,000 rat — was given first aid and reinflated.

(Honda strikers’ rat, in happier times.)

Real Money

Outside Illinois, the late Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen is probably best remembered for an ironic (and, it turns out, probably apocryphal) comment on federal spending. It went something like, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money.”

The quote, real or not, needs to be updated. A couple of economists — Columbia’s Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate and son of Gary, Indiana; and Harvard’s Linda Bilmes — are getting some attention for a new estimate of the Iraq War and its effects: $1 trillion to $2 trillion or more. When you include that with Bush’s other trillion-dollar-plus brainstorms — tax cuts for the rich, the new Medicare prescription benefits, Social Security semi-privatization — pretty soon you’re talking real money.

The up-front costs for Iraq, Afghanistan and the rest of the war that will never stop are staggering enough: something like $325 billion already. The amount spent on Iraq is about three-fourths of that number, about $230 billion; that works out to just under $7 billion a month since we decided to buy Iraqis their freedom from Saddam Hussein (oh — and remove the deadly threat to our future existence, too). We’ll spend another $50 billion to $100 billion in Iraq this year, depending on who you believe. After that — who knows. In a New York Times op-ed piece last August, Bilmes tallied the direct costs of the war at $1.3 trillion if the U.S. military presence is required for another five years.

Stiglitz’s and Bilmes’s reported analysis, which is supposed to be presented in Boston on Sunday at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association, tries to assess the war’s indirect costs, too. From an apparent press release posted Thursday on TPMCafe:

“The study expands on traditional budgetary estimates by including costs such as lifetime disability and health care for the over 16,000 injured, one-fifth of whom have serious brain or spinal injuries. It then goes on to analyze the costs to the economy, including the economic value of lives lost and the impact of factors such as higher oil prices that can be partly attributed to the conflict in Iraq. The paper also calculates the impact on the economy if a proportion of the money spent on the Iraq war were spent in other ways, including on investments in the United States

” ‘Shortly before the war, when Administration economist Larry Lindsey suggested that the costs might range between $100 and $200 billion, Administration spokesmen quickly distanced themselves from those numbers,’ points out Professor Stiglitz. ‘But in retrospect, it appears that Lindsey’s numbers represented a gross underestimate of the actual costs.’ ”

Of course, by themselves, these numbers don’t carry any moral weight. It’s just money, and we’ll get someone to float us a loan for the kids and grandkids to pay off. But as an example of the dishonesty, irresponsibility and self-delusion behind the war, the figures are staggering. A recent Brookings Institution paper that tries to come to grips with the war’s cost notes, “Government policies are routinely subjected to rigorous cost analyses. Yet one of today’s most controversial and expensive policies—the ongoing war in Iraq—has not been.” In other words, while spending commitments for education and social welfare have to survive the equivalent of a budgetary Inquisition, Congress has been happy so far to fund Iraq based on any wild-ass guess the White House feels like making.

Not that everyone was as casual about the war’s cost as those who launched it: Yale economist William Nordhaus published an analysis of potential costs two months before the war started that concluded the direct and indirect expense might total nearly $2 trillion if the conflict were “protracted and unfavorable.”

Getting It Straight

The New York Times ran a nice little commentary Tuesday on the factual reliability of Wikipedia, the collaborative online reference to everything, and the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the hoary compendium of everything worth knowing. The Times mostly recapitulates the findings of a study published last month in Nature that compared science entries in the Wikipedia, which depends on community writing and editing, and Britannica, which relies on subject experts for its authority. An encyclopedia open to all comers to add to and alter at will would seem fraught with risk and likely to be rife with errors compared to a work created under strict editorial control. But the Nature study sampled 42 entries in both works and found that Wikipedia articles contained four errors per article on average; Britannica articles contained an average of three errors.

I’ve made my living in a media culture that believes in the importance of accuracy and quality and refinement — qualities best obtained, it is widely believed, by employing someone like me. At the same time, I’ve lived in terror of the blind, witless blunder that makes it into print; either under my name or worse, by my hand under someone else’s name. The fear comes from having learned that editorial perfection is a moving target: The state of knowledge on most subjects is ever evolving and changing. One minute someone has never had sex with that woman, Miss What’s-Her-Name; the next they’re apologizing for the sex they had with her. Follow that? It’s not so different, really, from trying to keep your facts straight on politics, history, religion, science, or theories of modern marketing. The best you can do is aim to be correct at a given moment and be ready to reassess your work the minute you see it out in the world.

So it’s not surprising to find the Encyclopaedia Britannica isn’t the unassailable tower of knowledge some of us might like to believe it is. What’s more surprising, to me, is that the masses, turned loose on a universal encyclopedia project, don’t do so badly. The Times’s commentary has a nice simile for how it works:

“It may seem foolish to trust Wikipedia knowing I could jump right in and change the order of the planets or give the electron a positive charge. But with a worldwide web of readers looking over my shoulder, the error would quickly be corrected. Like the swarms of proofreading enzymes that monitor DNA for mutations, some tens of thousands of regular Wikipedians constantly revise and polish the growing repository of information.”

“Thousands of regular Wikipedians” is the key. Editors are important. It’s just that they don’t need a special license or a paycheck from a publisher to do the work passably well.

Rain

It’s raining again this afternoon. Off the top of my head, the last day it didn’t rain here was Christmas Eve. It rained every day for a week before that. Up till then, we’d been having a dry December; a dry fall, for that matter. It’s not unusual during our Decembers, Januarys and Februarys to get 10 or 11 or 12 or 14 wet days in a row. What seems a little unusual about the current one is how much rain we’ve gotten. As carefully but unofficially extracted from the UC Berkeley weather station data:

December 17: .41 inches

December 18: 2.33 [Berkeley Flood Terror]

December 19: .18

December 20: .15

December 21: .69

December 22: .81

December 23: .01

December 24 [Ark comes to rest, rainbow and dove appear, etc.]

December 25: .74

December 26: .35

December 27: .23

December 28: .61

December 29: .01

December 30: .94

December 31: 1.51

January 1: .47

January 2: .55

That’s a total of 10.07 inches in the last 17 days (not exceptional during the current storm cycle; my friend Pete told me about one location on the ridge to the west of the Napa Valley that may have gotten 30 inches for the month of December). The total today, Day 18, is .07. So far. The forecast for tomorrow. Dry.

The News from Equality

By way of Lydell, the Chicago Tribune, and the Associated Press, news from Little Egypt:

“EQUALITY, Ill. — No major damage was reported after a minor earthquake shook areas around this small town in southern Illinois on Monday.

“The quake struck at 3:48 p.m. and registered magnitude 3.6, according to Rafael Abreu, a geologist at the National Earthquake Information Center in Denver. It was centered near Equality, which is about 120 miles southeast of St. Louis.

“Abreu said calls from people who felt tremors came from Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky, but the quake was unlikely to have caused any damage.

” ‘There might have been some rattling of objects, but not much more,’ Abreu said.

An earthquake in Southern Illinois? Not too shocking, if for no other reason than the greater Equality area is only 100 miles or so as the crow flies from New Madrid, Missouri, near the center of some of the most powerful earthquakes in U.S. history.

But Equality‘s another matter. Just the name: There’s got to be a story behind that. If a local school district page is to be believed, the town was known as Saline Lick. In the 1820s, the name was changed to honor the settlement’s French heritage; Equality refers to the Egalité of the French revolutionary motto. But neither the name nor the school’s Web page hints at the town’s historical notoriety: A local landowner, John Crenshaw (said in one article to be a grandson of one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence), is remembered for his part in a sort of reverse Underground Railroad. He and his many cohorts kidnapped free blacks in the north and sell them into slavery. Crenshaw also made a fortune from salt processing, an operation that depended on hundreds of “leased” slaves. (Yes — slavery in the Land of Lincoln; in fact, Lincoln is reported to have been Crenshaw’s guest during a visit to the area in 1840). A tangible piece of this legacy survives: Crenshaw’s place, now called the Old Slave House, still stands a few miles from Equality.

‘Otherwise Occupied’

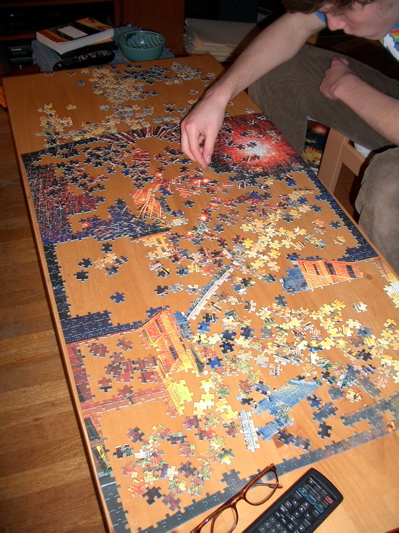

This is what I mean: The New Year’s Eve jigsaw puzzle. Twenty-three by thirty-eight inches. Fifteen hundred pieces. Ridiculous similarities among pieces that don’t belong together. Well, maybe not ridiculous. But challenging! We’re about one-third done, meaning the first big accomplishment of 2006 is only days away.