Well, it’s here. Rain, I mean. Not in copious, toad-strangling, gully-washing volumes. And I just heard a National Weather Service forecaster on the radio counsel patience — more will be coming later today, overnight, tomorrow. As I said the other day, we’ll take what we can get. In drought times, and even just at the end of our long summer dry spells, water falling from the sky carries an emotional weight way out of proportion to what shows up in the rain gauge.

Reprieve

So now we get to the part of the story where we’ll grasp at nearly anything as a sign of hope, or reprieve, or simple delay of the inevitable.. Last week, much of California was blasted with 110-degree temperatures, day after day after day. When you look that in the face, you ask yourself how much worse can things get and how much this corner of the world, a world where more and more people are suffering under more and more extreme conditions, will change. Then things cool down. Some areas will have high temperatures over the weekend nearly 50 degrees lower than the all-time highs registered last week. This weekend, all the weather models and their interpreters say, it’s going to rain, and rain enough that it will put a bit of a damper on (but won’t end) the fire season.

I’ll take it — just a day of rain to take the edge off the harsh, dry end of summer and our drought. I call it a reprieve, knowing that a reprieve can be just a postponement of what’s to come.

Moving East With the Murk

A predictable circumstance of this trip: that we’d see at least patches of wildfire smoke as we travel east. I mean, we’ve all seen the stories this summer, and the fires in California and elsewhere are still putting out major volumes of particulate matter. Even so, the image above, a screenshot of the map at fire.airnow.gov, is sobering. (That little blue dot at left center of the image is where we are now.)

Beryl Markham’s memoir “West With the Night,” an account of her history-making career as an aviator (including the first solo east-to-west crossing of the Atlantic) came to mind.

We’re now traveling east with the murk. Not nearly as hypnotically poetic as the image of flying into the twilight and the unknown. But we’re chasing our own sort of twilight adventure.

What Your Rain Gauge Says About You

To answer the question implicit in the title: I really have no idea.

But your rain gauge, be it an expensive electronic home weather station variety for which you’ve shelled out many hundreds of dollars or a humble plastic tube that you read manually, will tell you one thing for sure this winter in California: It’s been much drier than normal throughout our rainy season, and it’s dry now.

So far, our backyard gauge has caught 6.83 inches of rain since last July 1 (which is the “rainfall year” that used to be the standard for the National Weather Service in California; a few years ago, the agency switched to the “water year,” which runs from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30. For what it’s worth, I recorded exactly one one-hundredth of an inch (.01 inch) from last July 1 through Sept. 30; the Berkeley normal for that three months totals .31 inch).

Where was I? Right — 6.83 inches of rain since last July 1. The Berkeley “normal” for July 1 through March 8, as calculated for the “official” Berkeley station on the University of California campus, is 21.49 inches. One way to look at that: We’re about 15 inches short of our “normal” wet season rainfall. Another way: We’ve gotten just 31.8 percent of that “normal” precipitation.

I’d love to be able to compare my numbers with that station on campus, which has been keeping records since 1893. But I can’t right now. The Department of Geography employee in charge of the weather station and sending data to the public National Centers for Environmental Information database retired sometime in the last few months, and the most recent available numbers from that station are from last September. I’m told that the later data will be forthcoming … soon.

(Much later: The grad student in charge of collecting the UC Berkeley did get back to me after this was posted. The rainfall at the campus station totaled 7.99 inches at the time this post was published.)

Since the UC Berkeley info isn’t available, I’ve checked to see what other nearby CoCoRAHS (Community Cooperative Rain, Hail and Snow Network) rain watchers have recorded and compared those to the official Downtown San Francisco record for the season.

One gauge, 1.4 miles to the northwest in Albany, has recorded 6.99 inches since July 1 (.16 inch more than my gauge); another, 1.6 miles to the southwest in South Berkeley, has measured 6.39 inches (.44 less than mine). And San Francisco’s Downtown station, which has the longest continuous rainfall record on the West Coast — going back to the summer of 1849 — has picked up all of 7.41 inches since last July 1, or 39 percent of normal.

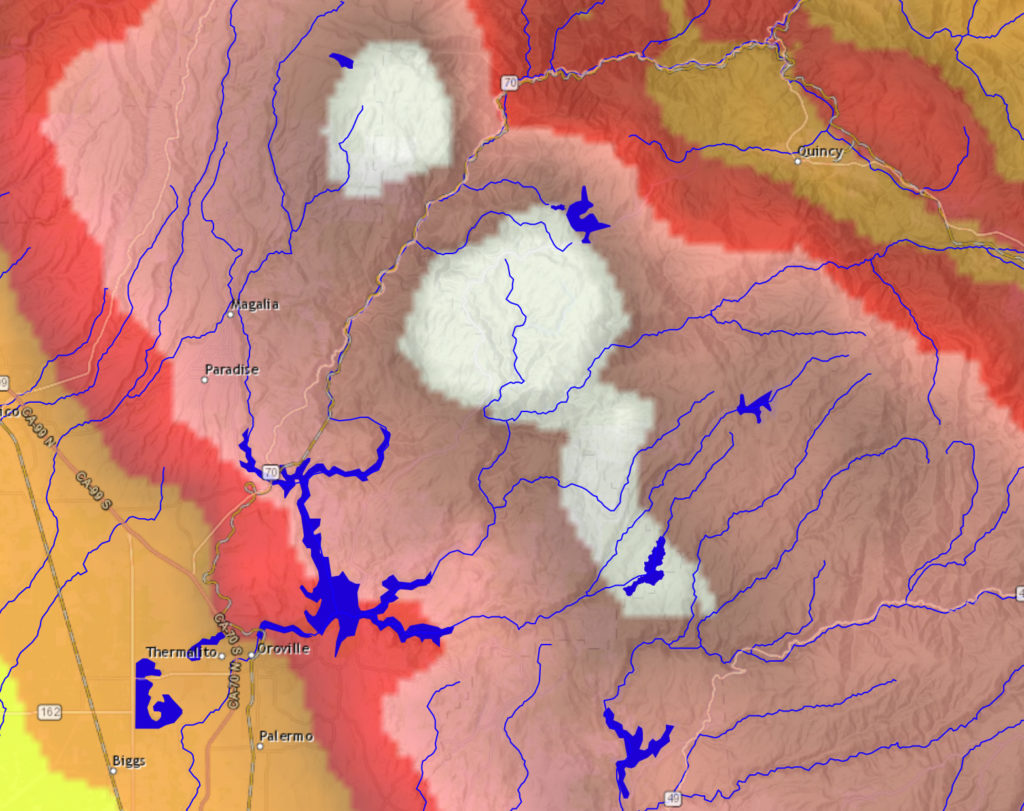

A look at the California-Nevada River Forecast Center makes it clear that our local percentages of normal — figures in the 30 to 40 percent range — are pretty typical across our slice of Northern California:

One other observation for now, by way of Jan Null, a former National Weather Service forecast who works as a consulting meteorologist. As he noted last week, California is in its second very dry winter in a row and we have a recent historical parallel, from 2013, that we can use to measure advancing drought effects across the state:

Watching Oroville as Storm Approaches

Not so long ago — through late February, say — the news about California’s “wet” season was how dry it had been. But that changed last month, when a series of late-season storms pulled the state back from the brink of a return to deep drought.

As the last March storm departed, I heard people asking, “Is that it? No more storms?”

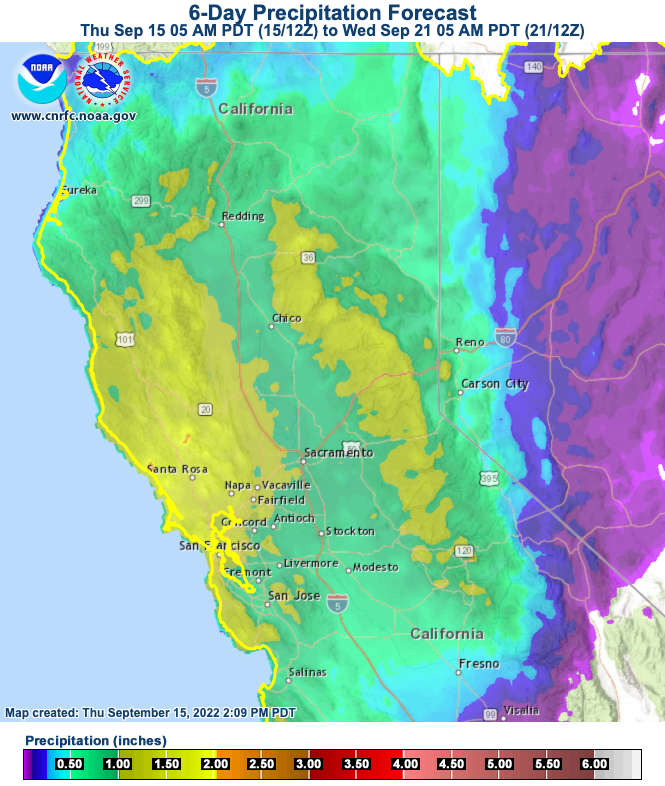

But model-watchers saw a return to wet weather late this week, and those supercomputer prognostications have been borne out in the form of a very warm, very wet storm that is forecast to dump huge volumes of water over the northern two-thirds of the state.

One of the regions forecast to get the heaviest deluge is the Feather River watershed, above Oroville Dam and Lake Oroville. That’s news because the California Department of Water Resources, which owns and operates the dam, may be forced sometime in the next few days to release water down the dam’s half-completed spillway.

The image above is from the California-Nevada River Forecast Center, and it depicts a precipitation forecast for more than 7 inches of rain in parts of the Feather watershed over the next 72 hours. (There’s an interactive version of the map on the CNRFC site, here.) DWR has, without a doubt, modeled the expected runoff from that much rain falling so quickly, how fast the lake will rise, and when it will reach the “target” elevation at which the spillway gates will open and water will flow down the 3,000-foot-long concrete chute.

As of this morning, the reservoir is about 20 feet below the lip of the spillway inlet and about 37 feet below the target elevation of 830 feet above sea level. From outside, it’s hard to guess how quickly the lake might rise — that’s a function of the total precipitation, how saturated soils in the watershed are, how much snow might melt off in the watershed’s upper reaches, and how much water is released from the reservoir through the only currently available outlet, the dam’s hydroelectric plant. But given the rate of the lake’s rise during the last round of heavy rain, it would appear that it would be late next week before that 830 foot threshold is reached.

Here’s the current DWR statement on reservoir conditions and prospects for a spillway release.

Today It Rained

Today it rained. Those droplets on the flowering quince up there above are the proof. Our non-fancy rain electronic rain gauge reads .04 of an inch for the day. And since this was the first rain since January 25, that makes .04 of an inch for the month, too.

As California climatologists are quick to point out, longish dry spells are not unusual during California’s wet season. But this long dry spell matches one we had in December, when we got just .12 of an inch. Those two dry months came sandwiched around a pretty average January — 4.77 inches according to our rain gauge. So adding up the last two and a two-thirds months, we’ve gotten less than 5 inches of rain, total.

As in most of the rest of California, December, January and February are the three wettest months of the year. The official Berkeley record shows an average total for those three months, since 1893, of 13.16 inches. The December-January-February average for the 1981-2010 climate “normal” was significantly higher — 15.23 inches. (That’s a pretty wide spread, and it’s probably due to many months of missing data over the last 125 years.)

A year ago — our one really wet winter in the last six, we got 9.85 inches in February alone. Our D-J-F total for 2016-17 was 28.63 inches.

Of course, February isn’t over yet. More chances of rain are forecast over parts of Northern California for the next week. We’ll see how that pans out.

Eclipse Day: Casper, Wyoming

Well, just under over three hours to T-Time. T for totality. The sky is clear but a little smoky here. Off to the north, a bank of high clouds is visible. Is it headed this way?

From the final, very complete forecast discussion published at 2:48 a.m. by the Riverton office of the National Weather Service:

“… Natrona county, including Casper, will lie within the other good area to view the eclipse as it will likely be mostly clear and sunny to begin the day with high clouds not making it into the County until after totality, through the afternoon. There is also one additional caveat to this astronomical event – smoke cover. The forecast area will see another frontal push through the area later this morning perhaps bringing in more wildfire smoke and causing or continuing some visibility decrease (keeping the sky a bit hazy side even without the clouds). Again, none of these factors will keep the eclipse from being viewed – but may somewhat limit how it/what can

be seen around the eclipse itself…especially near/at totality. On the other hand, the colors associated with this kind of filtering could be quite dramatic.”

One of Those Nights

It’s 11 p.m., and the temperature is 71 here in Berkeley.

That late-night warmth in mid-June would not be news in Chicagoland, where I grew up (the current temperature at Midway Airport, recorded at midnight CDT, is 78) or most of the rest of the country outside of the Pacific Northwest.

But here, 71 degrees as we move toward midnight is unusual; and reminiscent, though we don’t have midwestern humidity, of growing up in Chicago’s south suburbs.

Somehow, my parents grew up without air conditioning. We didn’t have it, either, in our house on the edge of Park Forest. It seemed impossible to sleep on really warm, humid nights, though I’m probably forgetting that fans helped.

Our dad would go to bed early; our mom was a night owl and would have some late-night TV on. Johnny Carson, maybe, or “The Late Show” movie. She’d let us stay up if it was too hot to sleep. If the night was oppressive and sticky, she’d have us take a cold shower to cool off.

Thinking back, Mom didn’t get her driver’s license until after our last summer in Park Forest. The next June — 1966, when I was 12 — we moved out to a new house built on an acre lot in the middle of the woods we had lived across the street from. It was like a jungle out there in the summer — green and moist and full of mosquitoes and lots of other wildlife.

Things changed once we moved out there. We had air conditioning. One unit upstairs, one downstairs. Outside, it might be dripping. Inside, it was miraculously cool and dry — a different world. I imagine the electric bills were staggering compared to what they had been at our old place.

Then, too, Mom had her license. Every once in a while, she’d invite us out on a late-evening jaunt — to the grocery store, or just to drive.

An Eye on the Eye of the Storm

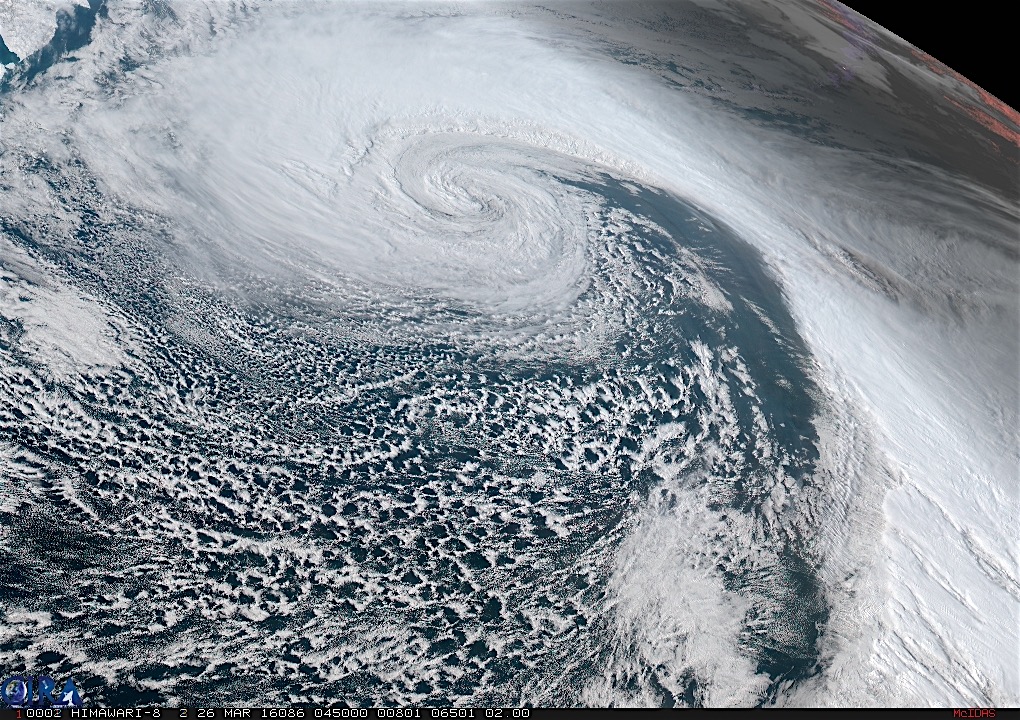

A few weeks ago, I downloaded a Chrome browser extension that, when you open a new tab, shows a current (or at least very recent) view of the full disk of the Earth as captured by Japan’s geostationary Himawari 8 weather satellite. Himawari produces high-resolution images of the Earth — the kind you can lose yourself in for hours if that’s the kind of thing you like.

Anyway, I noticed last Friday and Saturday that the full-disk image was showing a huge storm someplace in the northeastern Pacific. I wondered whether I could find a better view of the images online, and sure enough, NOAA’s Regional and Mesoscale Meteorology Branch (RAMMB to its friends), which inventories a lot of satellite images, features a Himawari Loop of the Day.

The loop for Saturday, March 26, was titled “Intense Low in the North Pacific.” Hit that link and it takes you to a movie — you need to have a little patience for the download — of the storm I was seeing in the full-disk picture. The image above is a frame from the movie.

It’s extraordinary. Or maybe everything on Earth is extraordinary if you have a chance to sit back and watch it for a while.(One note on the movie: A shadow crosses toward the end: that’s night falling as the Earth rotates. But the surface details are still visible because of GeoColor, a system that blends visible (daytime) and infrared (nighttime) imagery. GeoColor is also responsible for the reddish appearance of cloud tops in the nighttime images.)

Below is what the storm looked like on a conventional surface weather map: a sprawling, intense system with sustained winds over 60 mph forecast to occur 500 miles and more to the south and southwest of its center. The storm was producing monstrous waves, too, with seas as high 34 feet.

The Control of Nature: Primitive Hydraulics

Sunday morning: Still raining.

We’ve had .42 of an inch so far today (it’s 1:30 p.m. daylight-saving style) to go with the 6.48 over the past nine days.

The rain has prompted me to return to an old wet-weather routine that Kate and I have called, in a nod to a favorite writer and a favorite series of articles in The New Yorker, “the control of nature.”

When we moved into our house in April 1988, it was noted in some document somewhere that there was a sump pump on the premises. I found out where the pump was and why it was there the following winter.

Our house has a crawl space. Our lot is on a slope paralleling the course of Schoolhouse Creek. The stream itself has been moved underground, but as we found out one very wet December day a little more than 10 years ago, too much water arriving all at once can, along with a clogged storm drain upstream, bring the creek back above ground.

Water appears less dramatically in our crawl space, and that’s why there’s a sump pump down there.

Usually, a murky pool will gather in a spot that’s been excavated to allow access to the crawl space. Sometimes, as in deluge that arrived early the morning of New Year’s Day 1997, the space will start to fill. That was the one and only occasional the pump, installed in a little concrete well built around our floor furnace to keep the heater from getting flooded, turned on.

Perhaps one reason the pump hasn’t been more active is because I try to keep the crawl space drained when I see water gathering there.

Control of nature requires gravity and a garden hose. I take the full hose, stick one end of it into the watery crawl space. Then I run the hose down the driveway — 30 to 40 linear feet and 3 to 4 vertical feet — to the street.

I set the hose running last night about 9 o’clock. It’s still running. How much water has come out of there in that time?

I tried to calculate the rate by measuring the flow into a 1-cup measure (yes — this has the possibility of introducing a large error; but let’s just agree I’m not being perfectly scientific). In four trials, the cup filled up in about 6 to 7 seconds. Based on that, I figure somewhere between 32 and 38 gallons are draining out every hour. And that would put the total for the 15 hours or so the thing has been running at 480 to 570 gallons. Which is more than I would have guessed.