Reflecting a little on what’s happened this week, and on this very disturbing piece of business here — an interview with the most straightforward, thoughtful, well-spoken white supremacist you’ll ever encounter, and all the more disturbing for that — it occurred to me once more how eager our white society has been to put its grossest transgressions in the rear-view mirror and act as if, now that we’ve resolved that little problem to our own satisfaction, everyone should move on. Nothing to see here, folks, but lots of unpleasantness we can just leave behind.

Listening to Richard Spencer, the white “nationalist” referenced above, talk about his ideas for a white “ethnostate” and his belief that at bottom, the governing sentiment among those of different races is hate, I was struck by his unwillingness or inability to confront the toughest question his African-American interviewer threw at him:

What’s the difference between you and the racists that like, you know, hung people up from trees? What’s the difference between you and the Klansmen that burned crosses on peoples lawns? What’s the difference between you and you know, the people who don’t look at me, an African-American man, as a full human being?

After dodging and weaving a little and saying he would not engage with the notion of “a hypothetical Klansman,” Spencer said this:

I’m sure there is some commonality between these movements of the past and what I’m talking about. But you really have to judge me on my own terms. Like I am not those people and I don’t fully know, I don’t know in the specifics of what you’re referring to. Like I am who I am. And you, if you’re going to treat me with good faith, you have to listen to what I’m saying and listen to my ideas. I think someone who would go down the path of becoming a Klansman or something in 2016, I think that is, those people are very different than I am. It’s, it’s a it’s a non-starter. I think we need an idea. We need a movement that really resonates with where we are right now.

He and his ilk are different because — well, they are. You just have to trust him on that. And besides, it’s 2016 and we need to put that behind us and pursue a grander idea. (At one point in the interview, Spencer shares a few of the “values” he holds dear: “greatness and winning and dominance and beauty.” That list brought a name to mind: Leni Riefenstahl.)

The grand idea is, as mentioned before, a “white ethnostate,” what he terms “a new type of society that would actually be a homeland for all white people. … All European people … [so] we would always have a safe space.”

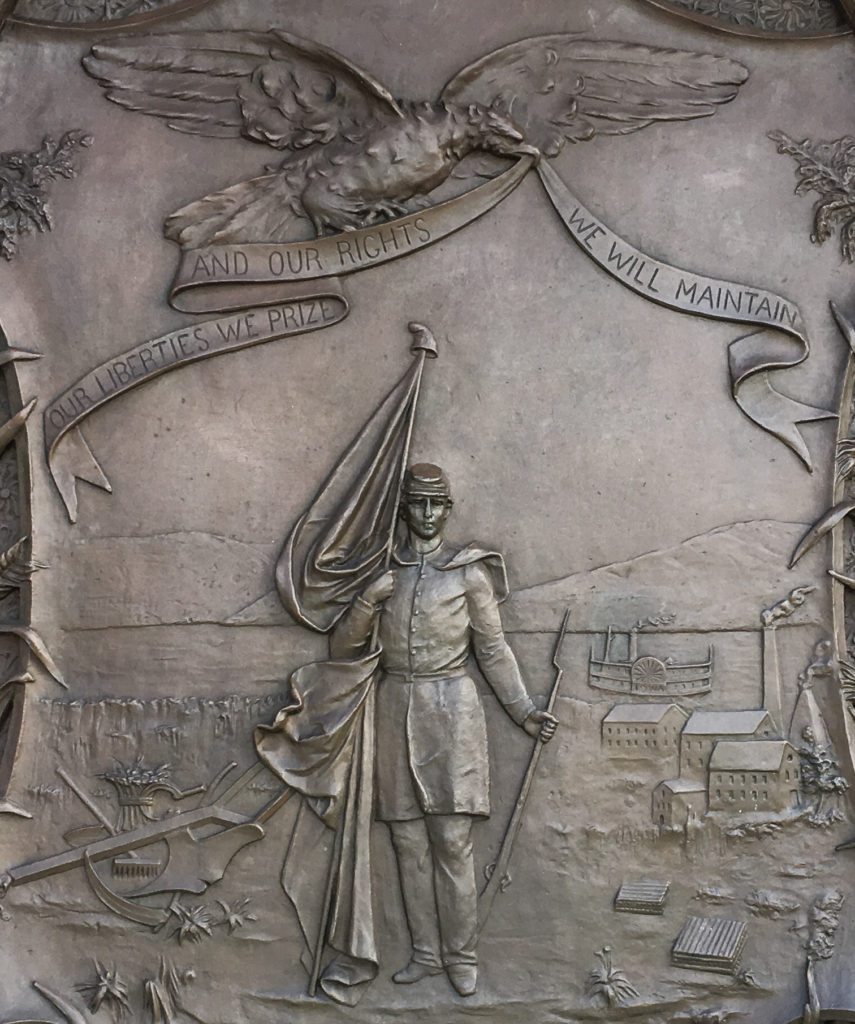

This isn’t really a new idea, as he says. He points to Israel as such a state. But of course there’s an example much closer to home — in fact, a state founded on the very same principles of white supremacy that underlies the idea of white nationalism.

Many of us treat the Confederacy and the Civil War and the long siege of Jim Crow that followed as objects in the rear-view mirror; curious, glorious or shameful objects that have receded almost from view. Let them stay in the past.

Lincoln was one who understood the past has its claims, and that it’s not so casually left behind. In his Second Inaugural, delivered a little more than a month before the war’s end and his assassination, he spoke about how each side had called on divine support for its cause:

“Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.”

And it was beyond humans, Lincoln said, to understand what price providence might demand for the crime of slavery. It was beyond us to know when the debt had been redeemed.

“‘Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.’ If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.'”

I think the first time I encountered the address was at the Lincoln Memorial, where it’s inscribed in marble. That passage — “until all the wealth piled … until every drop of blood drawn ” — has always stuck with me.

First, I think, because of Lincoln’s sober consideration of the magnitude of the “offense” that had led to the war.

Second, because of his suggestion that there was no way of knowing when the nation’s offense would be expiated — or even whether it could be expiated.

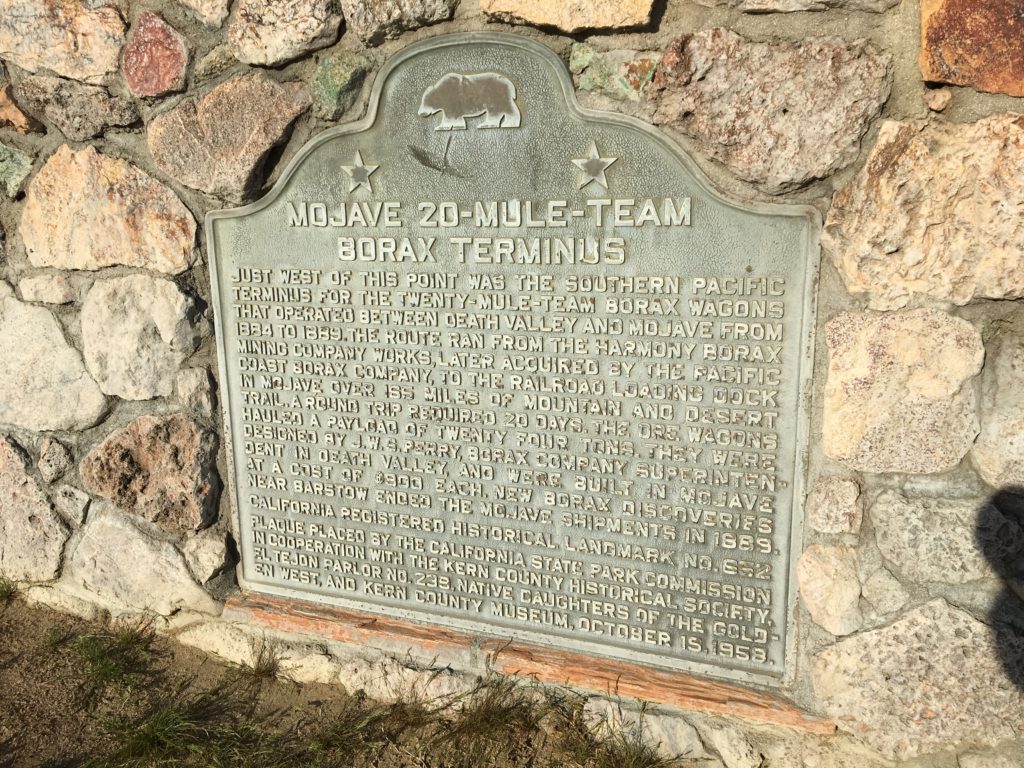

And third because, even though I am not one of Lincoln’s faith and I don’t imagine an omnipotent deity who wills human cruelty and then doles out punishment for it, the renewed encouragement of racial hatred we’re seeing now makes it clear that we’ve yet to really reckon with the worst chapters of our history — slavery, Native American genocide, the Klan’s reign of terror, Jim Crow, mass incarceration. And now, it seems, we’re listening to people who are eager to write the next dark chapter of history.

Like this:

Like Loading...