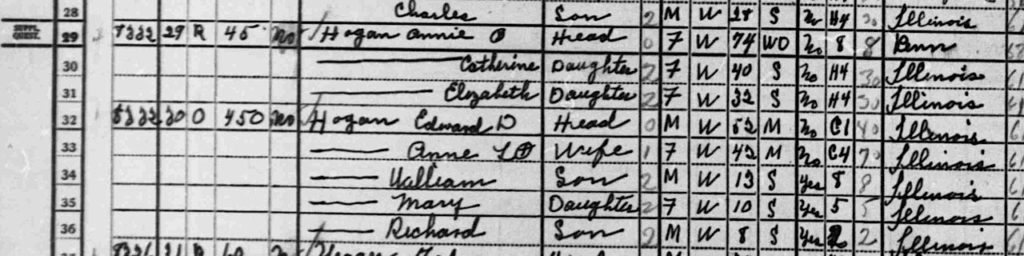

The west side of the 8300 block of S. May Street, Chicago, in the 1940 census (click for a larger version.)

A while back, it occurred to me I’d better start recording the basics of some of the “how we’re related” family stories I’d heard for a long time from my mom and dad. Not that the stories are terribly complex in my immediate family. My dad is an only child (translation: I have no first cousins on his side of the family). My mom was the only girl among six children; of her five brothers, four lived to adulthood, and all of them became Roman Catholic priests (translation: no first cousins, or rumors of first cousins, on her side of the family). A generation back, though, and there were lots of kids. Both of my grandmothers came from big families, and each of my grandfathers have four or five adult siblings. That’s enough to create some complicated relationships, and as my parents’ generation has passed on–my mom died in 2003, the last of her siblings followed just a few months later, and at 90 my dad has likely outlived all his first cousins–there’s no one left to explain how all those family members you happen across in a cemetery or family tree relate to each other.

So, I’ve become mildly proficient at sorting through census records, and when the 1940 census came out this week, I was interested in tracking down family members.

But the 1940 data has a twist: There’s no name index. Meaning that you can’t find your relatives by going to some nicely organized website, plug a name in to a search blank, and find them in the census (that will come later, after the Mormon-organized army of volunteer transcribers does its work). Instead, you need to know where your family lived–and the more precise the idea you have, the better. In the case of some of our Chicago family, I know my mom’s and dad’s childhood addresses off the top of my head. Those are places we visited as kids and have been back to, just to take a look at them, as adults. At some point over the last decade or so, I also figured out my mom’s mom’s parents exact address on the South Side.

The newly released records are organized by Census Bureau Enumeration Districts: the patches of territory assigned to the 120,000 census takers who recorded the 1940 population. An enumerator was supposed to be able to cover an urban district in two weeks, a rural one in four weeks. For city areas, that was at least 1,000 people, and an enumerator might fill out forty pages of census schedules (forty people to a page) while visiting every domicile in the district.

As I said, there’s no way of digging individual names out of the millions of pages of census records released this week. But through the work and technological savvy of a brilliant San Francisco genealogist named Steve Morse, you can find people if you have a reasonably precise idea of where they lived. Morse created a site called the Unified 1940 Census ED Finder, which is the front end for a database that apparently contains information on every block of every street in every U.S. community. If you know someone lived at West 83rd Street and South Racine Avenue in Chicago, Morse’s site allows you to plug that information in, along with other cross streets, and discover the enumeration district where your person lived.

In 1940, my mom’s family lived in the 8300 block of South May Street, a block over from 83rd and Racine. Morse’s site shows that was Chicago Enumeration District 103-2222. The enumerator, Bezzie K. Roy, filled out thirty-six schedule pages in visiting the district’s households. You never know when you start looking through those thirty-six pages whether you’ll find the people you’re looking for on the first page or the last–I think you’re at the whim of the enumerator, though maybe there was a method to the job (for instance, start at the west edge of a district and move east, or something like that). In this case, Bezzie Roy visited my mom’s block on page three.

The family lived in a two-flat building. My mom, who was 10 when the census was taken, lived on the ground floor with her parents and four brothers. Her grandmother — her father’s mother — lived upstairs with two of her grown daughters (such a deal for my grandmother, living downstairs from her in-laws). There they are, eight lines at 8332 S. May Street. That in itself seems to be a mistake. My mom had identical twin brothers, Tom and Ed, who would have been 6 at this time and who are not listed here. It’s hard to imagine my grandmother, who was the one indicated as having supplied the information, not listing everyone in the family. Where are the twins?

The other thing I’m struck by in seeing this simple list of names is how much it doesn’t say. Edward D. Hogan, my mom’s father, had been diagnosed with lung cancer by this point and only had about 14 months to live. Eight months before this census record, my mom, Mary Hogan, had survived a drowning that killed John Hogan, one of her older brothers. A month after that, my mom’s grandfather, Tim Hogan, who lived upstairs, died. I’ve thought a lot about what it must have been like in their household at this time. But as you page through the records of this block and all the neighboring streets, it’s certain that other homes harbored stories that simply aren’t visible in this enumeration.

(Click the images for larger, readable versions).