NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE CHICAGO IL 1216 AM CDT TUE MAY 8 2012 ...DENSE FOG ESPECIALLY NEAR LAKE MICHIGAN TONIGHT... .LIGHT WINDS AND CLEARING SKIES HAVE ALLOWED DENSE FOG TO DEVELOP ACROSS MUCH OF NORTHEAST ILLINOIS AND NORTHWEST INDIANA...WITH DENSE FOG ALSO PUSHING INLAND FROM LAKE MICHIGAN. DENSE FOG WILL CONTINUE THROUGH MUCH OF THE OVERNIGHT BUT VISIBILITY MAY START TO IMPROVE FROM WEST TO EAST BY AROUND DAYBREAK AS WESTERLY WINDS INCREASE SLIGHTLY. ILZ006-014-INZ001-002-081300- /O.CON.KLOT.FG.Y.0013.000000T0000Z-120508T1300Z/ LAKE IL-COOK-LAKE IN-PORTER- INCLUDING THE CITIES OF...WAUKEGAN...CHICAGO...GARY...VALPARAISO 1216 AM CDT TUE MAY 8 2012 ...DENSE FOG ADVISORY REMAINS IN EFFECT UNTIL 8 AM CDT THIS MORNING... * VISIBILITY...LESS THAN A QUARTER MILE IN SOME LOCATIONS ESPECIALLY NEAR LAKE MICHIGAN. * IMPACTS...VISIBILITY MAY CHANGE RAPIDLY OVER SHORT DISTANCES MAKING TRAVEL HAZARDOUS. VISIBILITY MAY BE NEAR ZERO AT TIMES ALONG THE LAKE MICHIGAN SHORE. PRECAUTIONARY/PREPAREDNESS ACTIONS... A DENSE FOG ADVISORY MEANS VISIBILITIES WILL FREQUENTLY BE REDUCED TO LESS THAN ONE QUARTER MILE. IF DRIVING...SLOW DOWN... USE YOUR HEADLIGHTS...AND LEAVE PLENTY OF DISTANCE AHEAD OF YOU.

Road Blog: Sidewalk Sharpener

Late last Thursday morning, I went walking up Western Avenue from my sister’s place. Ultimate destination: the long-term-care/assisted-living facility (a.k.a. “nursing home”) where our dad landed after his most recent hospitalization for pneumonia. Secondary destination: Starbucks, for the coffee I hadn’t yet had.

On the way north, just across Touhy Avenue, I encountered the gentleman pictured above, sharpening scissors outside a beauty salon. I passed, went about 10 paces, thought “I don’t see that every day,” then doubled back.

His name is Richard Johnson. He was sharpening scissors for the salon workers engaged in the beauty trade. The open-air contraption he was using, he said, “was designed by a genius” — meaning himself. He’s an engineer by training and said that back in the ’60s he worked on ballistic missiles stationed at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. His sharpening contraption consists of what looks like an emery belt and a polisher that he runs off an electrical outlet. The cord snaked across the sidewalk into the salon. It was his first time at this particular establishment.

“Mostly I work at pet groomers. They’re always dropping their scissors and clippers.”

“The clients aren’t as cooperative as here,” I said.

“Yes–they always blame the dogs.”

The most urgent task he was facing the morning I met him was reconditioning some “texturizing” scissors for a woman who already had a client in the chair. He worked on them, tested the sharpness on his arm hairs, then worked on them a little more. Then he brought them into the shop. Looking inside, I could see the beautician making a few preliminary snips. Then Richard came back out with the scissors.

“They let them get rusty and dull, and then they expect miracles,” he said.

Friday Night (Chicago) Ferry

I’m not in the Bay Area to do our Friday night ferry ritual. So the next best thing was to do a Friday evening boat trip in Chicago. Ann (my sister) and Ingrid (my niece) and I drove downtown and caught a Wendella cruise from a dock just beneath the Michigan Avenue bridge over the Chicago River. The first third of the 90-minute cruise heads west to the South Branch of the river, heads down a little way, and turns around when it’s just below Sears (Willis) Tower. Then it head back out to the lake, goes through the Chicago River lock out to the lake (there’s a two-foot elevation difference between the lake and engineered river), then a short spin north from the mouth of the river, then south toward the planetarium and aquarium, then back into the river.

Yesterday featured shockingly fine mid-spring weather. It was a not-overly-humid 85 with a what we in the Bay Area call an offshore wind–the breeze was coming from the southwest and blowing out over the water, meaning the cooling influence of Lake Michigan was felt (and then only slightly) immediately along the shore. That beautiful day ended in a long evening of lightning, thunder, and pounding rain, and by mid-morning today the wind had turned around and was coming from the northeast, off the lake. The high here today was about 60. And on the boat this evening, it was quite cool. But as long as we were on the river, well below street level, there was hardly any wind. But I noticed that as soon as we headed out toward the lake, the tour guide who had been filling us in on the architectural scene along the river grabbed her gear and headed for the downstairs cabin. “I’ll be back,” she told me. “But the wind is blowing so hard out here you won’t be able to hear me.” The U.S. and Army Corps of Engineers flags flying at the western end of the lock were standing straight out in the breeze as we approached. I saw in the paper today that the lake’s surface temperature is 43 degrees near shore, and as soon as we got out into that wind, it felt–well, pretty cold.

Then we turned around and came out of the tempest, back through the lock, back down the river. The scene above: the new Trump Building (second tallest in Chicago, a sign at its base boasts), with the Wrigley Building at right (decked in blue as part of a commemoration of fallen Chicago Police Department officers).

Air Blog: To Chicago

I managed to miss my scheduled flight earlier today by attempting one too many last-minute tasks before I headed out the door to the airport (including the daily Last Task Before Leaving, walking The Dog). I took BART out to SFO and knew I was kind of cutting it close and got to the baggage counter to check my bag about five minutes after they’d stopped taking luggage for my flight. Since they want you to be on the same plane as your baggage (think about why that is), both I and my bag got moved onto the next flight about an hour later. That was fine by me (though I might have emoted more if the delay had been four or five hours). My substitute flight was late, and for some reason the trip seemed much longer than the three and a half hours it was.

But all that’s ancient history. I’m up on the North Side now, at my sister and bro-in-law’s place in West Rogers Park. It’s one of those perfect nights in Chicago, springtime or anytime: warm until well after midnight, but not humid enough that you feel like the warmth is hanging on you. It’s calm and a little hazy but clear enough to see the brightest stars.

Preflight Vision

Off to Chicago today on a family visit. The top item on the agenda: visiting my dad, who’s in a rehab facility/nursing home on the North Side of Chicago after two bouts of pneumonia over the past couple of months (and a more general cognitive and physical decline that’s goes back much further). He’s on oxygen now, is quite weak, and really needs round-the-clock care. My sister, Ann, was visiting him yesterday and put him on the phone. He sounded tired and small. But still Dad. I’m both looking forward to seeing him and feeling a little apprehensive about it.

But first, I have a flight to catch. I always look forward to that and feel a little apprehensive about it, too. I don’t like the whole airport process. (Enough said.) I love the view of the Earth from above, even if the look you get from 35,000 feet and 550 mph tends to obscure details and prevents lingering over anything you find interesting. The shot above is from my trip with Kate to New York last August. I’m always on the lookout for geographic features, natural or manmade, to orient me–mountain ranges, rivers, cities, highways. Here, we’re passing just north of Omaha, looking south across the city’s airport, Eppley Airfield, (here’s an overhead view from Google Maps). The water there is the Missouri River, which if you remember was very high late in the spring and throughout the summer. Council Bluffs, Iowa, is across the river on the left (east), Omaha is to the right (west). That’s Interstate 680 at the bottom, built right across the flood plain. It was closed in June and essentially destroyed by the high water. The I-680 junction with I-29 is at the lower left; I-29 was also closed and needed extensive repairs. (Click the picture for larger versions.)

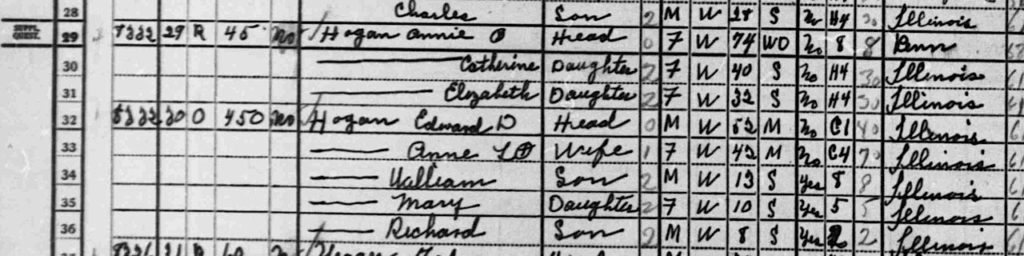

1940 Census: The Enumeration

The west side of the 8300 block of S. May Street, Chicago, in the 1940 census (click for a larger version.)

A while back, it occurred to me I’d better start recording the basics of some of the “how we’re related” family stories I’d heard for a long time from my mom and dad. Not that the stories are terribly complex in my immediate family. My dad is an only child (translation: I have no first cousins on his side of the family). My mom was the only girl among six children; of her five brothers, four lived to adulthood, and all of them became Roman Catholic priests (translation: no first cousins, or rumors of first cousins, on her side of the family). A generation back, though, and there were lots of kids. Both of my grandmothers came from big families, and each of my grandfathers have four or five adult siblings. That’s enough to create some complicated relationships, and as my parents’ generation has passed on–my mom died in 2003, the last of her siblings followed just a few months later, and at 90 my dad has likely outlived all his first cousins–there’s no one left to explain how all those family members you happen across in a cemetery or family tree relate to each other.

So, I’ve become mildly proficient at sorting through census records, and when the 1940 census came out this week, I was interested in tracking down family members.

But the 1940 data has a twist: There’s no name index. Meaning that you can’t find your relatives by going to some nicely organized website, plug a name in to a search blank, and find them in the census (that will come later, after the Mormon-organized army of volunteer transcribers does its work). Instead, you need to know where your family lived–and the more precise the idea you have, the better. In the case of some of our Chicago family, I know my mom’s and dad’s childhood addresses off the top of my head. Those are places we visited as kids and have been back to, just to take a look at them, as adults. At some point over the last decade or so, I also figured out my mom’s mom’s parents exact address on the South Side.

The newly released records are organized by Census Bureau Enumeration Districts: the patches of territory assigned to the 120,000 census takers who recorded the 1940 population. An enumerator was supposed to be able to cover an urban district in two weeks, a rural one in four weeks. For city areas, that was at least 1,000 people, and an enumerator might fill out forty pages of census schedules (forty people to a page) while visiting every domicile in the district.

As I said, there’s no way of digging individual names out of the millions of pages of census records released this week. But through the work and technological savvy of a brilliant San Francisco genealogist named Steve Morse, you can find people if you have a reasonably precise idea of where they lived. Morse created a site called the Unified 1940 Census ED Finder, which is the front end for a database that apparently contains information on every block of every street in every U.S. community. If you know someone lived at West 83rd Street and South Racine Avenue in Chicago, Morse’s site allows you to plug that information in, along with other cross streets, and discover the enumeration district where your person lived.

In 1940, my mom’s family lived in the 8300 block of South May Street, a block over from 83rd and Racine. Morse’s site shows that was Chicago Enumeration District 103-2222. The enumerator, Bezzie K. Roy, filled out thirty-six schedule pages in visiting the district’s households. You never know when you start looking through those thirty-six pages whether you’ll find the people you’re looking for on the first page or the last–I think you’re at the whim of the enumerator, though maybe there was a method to the job (for instance, start at the west edge of a district and move east, or something like that). In this case, Bezzie Roy visited my mom’s block on page three.

The family lived in a two-flat building. My mom, who was 10 when the census was taken, lived on the ground floor with her parents and four brothers. Her grandmother — her father’s mother — lived upstairs with two of her grown daughters (such a deal for my grandmother, living downstairs from her in-laws). There they are, eight lines at 8332 S. May Street. That in itself seems to be a mistake. My mom had identical twin brothers, Tom and Ed, who would have been 6 at this time and who are not listed here. It’s hard to imagine my grandmother, who was the one indicated as having supplied the information, not listing everyone in the family. Where are the twins?

The other thing I’m struck by in seeing this simple list of names is how much it doesn’t say. Edward D. Hogan, my mom’s father, had been diagnosed with lung cancer by this point and only had about 14 months to live. Eight months before this census record, my mom, Mary Hogan, had survived a drowning that killed John Hogan, one of her older brothers. A month after that, my mom’s grandfather, Tim Hogan, who lived upstairs, died. I’ve thought a lot about what it must have been like in their household at this time. But as you page through the records of this block and all the neighboring streets, it’s certain that other homes harbored stories that simply aren’t visible in this enumeration.

(Click the images for larger, readable versions).

Weathermen of Yesteryear

I grew up in Chicago, meaning I grew up on Chicago TV. In our house, the local news was a staple, and I’m inclined to believe it wasn’t bad though maybe it was also not as good as I sometimes tell myself it was. Anchor and reporter names I recall include Floyd Kalber, Frank Reynolds, Fahey Flynn, Bill Kurtis, Jane Pauley, Barbara Simpson, and Walter Jacobsen. Some of them went on to work with the national networks, for what that’s worth.

And then there were the weathermen. (Yes, they were all guys.) I think of them not because they were great, although I again lean toward the view they weren’t bad. I suppose there’s a book or at least a long essay on how we have come to see and think of the weather in the electronic meda age compared to earlier eras going back to the time when we guessed at the day’s conditions by looking to the horizon and sniffing the wind.

For better and worse, here are the weathermen who delivered the forecasts to my impressionable young mind:

P.J. Hoff, who cartooned the weather on the CBS affiliate, WBBM, Channel 2. He had a character named Mr. Yellencuss that I imagine he’d draw when bad weather was in the offing.

Harry Volkman, who worked on several Chicago channels and seemed to pride himself on (and was given credit for) the “professionalism” of his forecasting (he’s the first TV weather guy I recall displaying a seal from the American Meteorological Society during his broadcasts).

John Coleman, part of the first “happy-talk” Chicago news team on Channel 7, WBKB (later, WLS). In my book, his claim to fame, which was a pretty good one, was to forecast Chicago’s January 1967 blizzard (while he was doing weather on Milwaukee TV). According to his own account (in the comments to a post about Chicago’s Groundhog’s Eve Blizzard of 2011), Channel 7 hired him immediately after the storm, and I kind of remember him on Channel 7 by the time another storm hit two weeks or so after the first one). He went on to national TV and was a cofounder of The Weather Channel. And today, bless him, he’s a loud voice in contesting the case for climate change.

There were others, but they’ve faded from memory if in fact they ever made much of an impression. I ought to mention Tom Skilling as a great Chicago weather guy–the greatest, for my money–but he is very much of the present era.

Family History Files: Tim Hogan

A long-ago teacher of mine–G.E. Smith, who taught English, literature, and a lot more at Crete-Monee High School in the 1960s and '70s–became interested in his family ancestry late in life. It wasn't an easy thing. I don't know a lot of his personal story, but I do know that his mother left his biological father very early in his life, back in the mid-'20s, and that he was raised by a stepfather he remembered as generous if not saintly.

Also late in life, he brought out a book of poems he had written as a much younger man. He hadn't intended to, he said, but when he started into the family history business, his work took on a different meaning: "It wasn't until I began to think, as a genealogist, about how anything written by ancient relatives–even in signature–was (or could have been) so extraordinarily precious that I decided to consider publishing. I realized that I, too, someday, would likely be a long-ago ancient relative to someone who was pursuing my family history."

That line about the actual words of a forebear being "so extraordinarily precious" stuck in my head. I've listened to perhaps hundreds of hours of stories about my dad's family and my mom's, and recently I was struck with a little sense of urgency about setting down at least the basic outlines of what I've heard. So far, that's mostly involved cemetery visits and creating the beginnings of a family tree (through the very expensive and sometimes-worth-it Ancestry.com). There's a bit of an addictive thrill in tracking down someone you've been hearing about your whole life in a century-old census record: Wow–there they are, just like Mom and Dad said, in Warren, Minnesota, or on South Yale Avenue in Chicago. But records only take you so far, and they don't really give a voice to the people listed on the census rolls or on the draft records or on Ellis Island arrival manifests.

I imagine my family is like most in that whatever words were ever written down have mostly fallen victim to fastidious housecleaning, negligence, dismissiveness, or lack of interest. You know: "Who'd ever be interested in that?" or, "Does anyone want this old stuff?" (I think pictures are the occasional exception to this rule. Plenty get thrown away, but the images have an intrinsic interest for a lot of people when they can't readily identify the subjects of the photos.) Chance, mostly, and, less often, selection determine what survives. My dad has a collection of letters his father wrote to his mother during their courtship and early in their marriage, a century and more ago. I believe they are numbered and I remember hearing that after my grandfather, Sjur Brekke, died, in their 26th year of marriage, my grandmother continued to read those letters for years afterward. There used to be another set of letters, too–my grandmother's letters to my grandfather. But at some point she destroyed them. The story I've heard is that she considered them too personal for others to read. Wouldn't we Brekke descendants love to get a look at those.

Over to my mom's side of the family: They were Irish and stereotypically more voluble than my dad's Norwegian clan. But not much has survived (that I know about) beyond the oral tradition. One rather amazing exception: my mom's grandfather.

I don't know a lot about him, but Timothy Jeremiah Hogan was born in Ottawa, Illinois, in 1864 (I'll let him tell that story), lived as a child on the Great Plains (ditto), raised a family, including my grandfather Edward Hogan, in central and northern Illinois. He was a railroad man, working for one of the roads back there (on the Wabash, I believe, but don't know for sure). He was said to have spent a lot of time riding alone in the caboose and taught himself to play the guitar. He was losing his hearing at the end of his life, was described as taciturn and short with most of his grandchildren, and was reportedly heartbroken when a favorite grandson drowned in the summer of 1939. He died himself a month later.

Another thing about Tim Hogan: He had a typewriter, and he used it. He composed poems on the typewriter, and song lyrics. Here's one of his poems, about two of my mom's brothers (that's them in the picture at right) shortly after their first birthday:

October 7th.1934.

AN ODE TO OUR LITTLE

TWIN BOYS TOM, AND ED

*********************

Early in the morning

When they open up their eyes

Laying in their tiney little beds

Rolling over, over

Both the same size

Cunning little round bald heads.

You couldent help but love them

With their smileing eyes of blue

Remember it was GRAND DAD told you so,

Charming little twinners,

Only new beginers

You can almost see them grow.

Tim wrote letters, too. We only have a handful of them, but below are a couple that he produced in 1936 when he was trying to do a little biographical/genealogical research of his own. The first (click pages for larger images; full text is after the jump) is to the clerk of LaSalle County, and he's hoping to find records of his family's residence from around the time of his birth.

The second letter is to the Railroad Retirement Board. He doesn't explicitly mention it here, but I recall a couple of my mom's aunts, Tim's daughters Catherine and Betty, saying he was trying to establish his date of birth in relation to a pension that might be due.

One question I have about these: Did he send them? As he says, he's earnestly interested in getting answers. So my guess is that these are copies of versions he sent. I haven't found any records in the sparse collection of family documents to suggest what answers he might have gotten. The full text of the letters is available through the link below. If the lines break in an odd way, it's because I tried to stick to how he broke the lines, starting nearly each new line with a capital letter. I've also tried to copy his punctuation and spelling.

Family History Files: Tim Hogan

A long-ago teacher of mine–G.E. Smith, who taught English, literature, and a lot more at Crete-Monee High School in the 1960s and '70s–became interested in his family ancestry late in life. It wasn't an easy thing. I don't know a lot of his personal story, but I do know that his mother left his biological father very early in his life, back in the mid-'20s, and that he was raised by a stepfather he remembered as generous if not saintly.

Also late in life, he brought out a book of poems he had written as a much younger man. He hadn't intended to, he said, but when he started into the family history business, his work took on a different meaning: "It wasn't until I began to think, as a genealogist, about how anything written by ancient relatives–even in signature–was (or could have been) so extraordinarily precious that I decided to consider publishing. I realized that I, too, someday, would likely be a long-ago ancient relative to someone who was pursuing my family history."

That line about the actual words of a forebear being "so extraordinarily precious" stuck in my head. I've listened to perhaps hundreds of hours of stories about my dad's family and my mom's, and recently I was struck with a little sense of urgency about setting down at least the basic outlines of what I've heard. So far, that's mostly involved cemetery visits and creating the beginnings of a family tree (through the very expensive and sometimes-worth-it Ancestry.com). There's a bit of an addictive thrill in tracking down someone you've been hearing about your whole life in a century-old census record: Wow–there they are, just like Mom and Dad said, in Warren, Minnesota, or on South Yale Avenue in Chicago. But records only take you so far, and they don't really give a voice to the people listed on the census rolls or on the draft records or on Ellis Island arrival manifests.

I imagine my family is like most in that whatever words were ever written down have mostly fallen victim to fastidious housecleaning, negligence, dismissiveness, or lack of interest. You know: "Who'd ever be interested in that?" or, "Does anyone want this old stuff?" (I think pictures are the occasional exception to this rule. Plenty get thrown away, but the images have an intrinsic interest for a lot of people when they can't readily identify the subjects of the photos.) Chance, mostly, and, less often, selection determine what survives. My dad has a collection of letters his father wrote to his mother during their courtship and early in their marriage, a century and more ago. I believe they are numbered and I remember hearing that after my grandfather, Sjur Brekke, died, in their 26th year of marriage, my grandmother continued to read those letters for years afterward. There used to be another set of letters, too–my grandmother's letters to my grandfather. But at some point she destroyed them. The story I've heard is that she considered them too personal for others to read. Wouldn't we Brekke descendants love to get a look at those.

Over to my mom's side of the family: They were Irish and stereotypically more voluble than my dad's Norwegian clan. But not much has survived (that I know about) beyond the oral tradition. One rather amazing exception: my mom's grandfather.

I don't know a lot about him, but Timothy Jeremiah Hogan was born in Ottawa, Illinois, in 1864 (I'll let him tell that story), lived as a child on the Great Plains (ditto), raised a family, including my grandfather Edward Hogan, in central and northern Illinois. He was a railroad man, working for one of the roads back there (on the Wabash, I believe, but don't know for sure). He was said to have spent a lot of time riding alone in the caboose and taught himself to play the guitar. He was losing his hearing at the end of his life, was described as taciturn and short with most of his grandchildren, and was reportedly heartbroken when a favorite grandson drowned in the summer of 1939. He died himself a month later.

Another thing about Tim Hogan: He had a typewriter, and he used it. He composed poems on the typewriter, and song lyrics. Here's one of his poems, about two of my mom's brothers (that's them in the picture at right) shortly after their first birthday:

October 7th.1934.

AN ODE TO OUR LITTLE

TWIN BOYS TOM, AND ED

*********************

Early in the morning

When they open up their eyes

Laying in their tiney little beds

Rolling over, over

Both the same size

Cunning little round bald heads.

You couldent help but love them

With their smileing eyes of blue

Remember it was GRAND DAD told you so,

Charming little twinners,

Only new beginers

You can almost see them grow.

Tim wrote letters, too. We only have a handful of them, but below are a couple that he produced in 1936 when he was trying to do a little biographical/genealogical research of his own. The first (click pages for larger images; full text is after the jump) is to the clerk of LaSalle County, and he's hoping to find records of his family's residence from around the time of his birth.

The second letter is to the Railroad Retirement Board. He doesn't explicitly mention it here, but I recall a couple of my mom's aunts, Tim's daughters Catherine and Betty, saying he was trying to establish his date of birth in relation to a pension that might be due.

One question I have about these: Did he send them? As he says, he's earnestly interested in getting answers. So my guess is that these are copies of versions he sent. I haven't found any records in the sparse collection of family documents to suggest what answers he might have gotten. The full text of the letters is available through the link below. If the lines break in an odd way, it's because I tried to stick to how he broke the lines, starting nearly each new line with a capital letter. I've also tried to copy his punctuation and spelling.

R.I.P., Mary Dahl

Kate took this one during an August visit to Mount Olive Cemetery, up on the North Side of Chicago. It’s where my dad’s people are, and it’s impressive to see such a collection of Danes, Swedes, and Norwegians in one place. Every once in a while–pretty frequently, actually–you come across a headstone that, with only names and dates, seems to tell a story. In this case: the three short lives of Mary Dahl.

Briefly, here’s what I can find through looking at some genealogical records. George and Mary Dahl (nee Marie Johnson) arrived in Chicago from Norway in 1883 and ’86, respectively. George and Mary had several older children, born in Norway. Their first American-born child apparently was Mary II, born in January 1889. A Cook County death certificate (below) says she died on June 28, 1893. The cause: croup, which according to contemporary reports killed hundreds in Chicago that year and was perennially listed, along with diphtheria, another disease that involved airway obstruction, as a leading cause of death for children.

So where does Mary III come in? A Cook County birth certificate (middle document below) lists the birth of a baby girl named Marie to George and Marie (Johnson) Dahl on August 18, 1893. In other words, just seven weeks after the death of Mary II. By the 1900 Census, both Marie, the mom, and Marie, the daughter, are listed as Mary. (If not for the headstone inscription, that could be dismissed as a census enumerator’s error. The 1900 Census also lists Mary I, the mother, as not speaking English.)

My no-longer-quick search doesn’t find any documents for Mary III’s death in 1903. It does turn up a death certificate for Mary I, though, on April 14, 1908, age 59. Cause of death: carcinoma of the stomach. Under “duration of cause,” the document says three years and one month.

Update: I went back to the FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com databases to look again for the death of Mary Dahl III, born in August 1893. This time I chanced across a record on Ancestry that I hadn’t been able to find because whoever wrote out the death certificate (bottom) had misspelled her last name as “Diahl.” She died April 26, 1903, of “brain fever” with a contributing cause of “convulsions.”