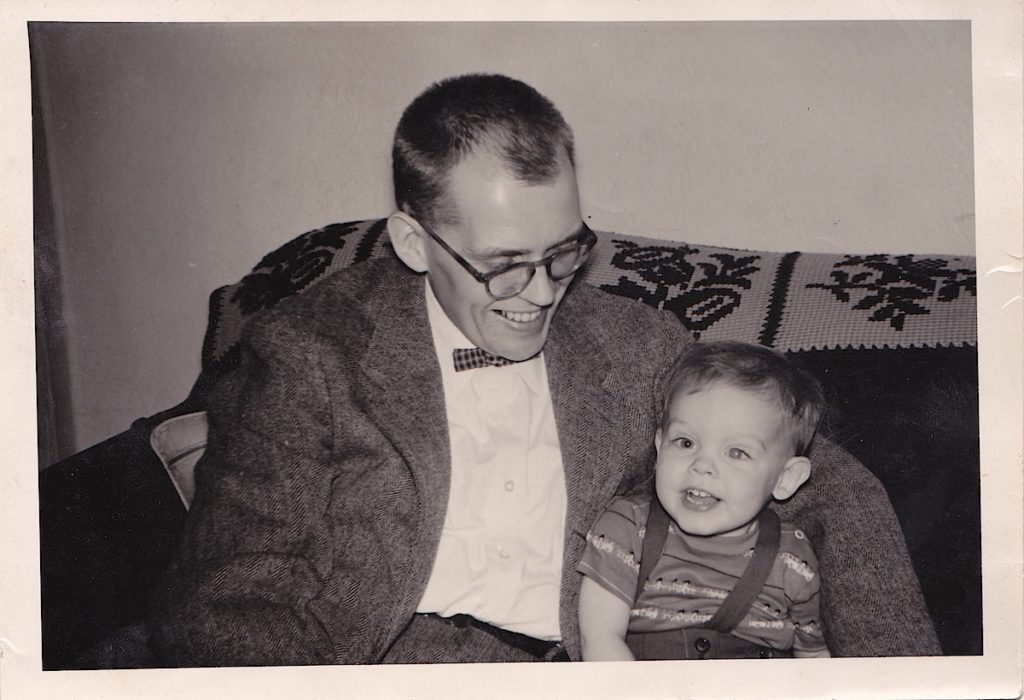

It’s my last night in Chicago for a while — now early morning, actually. I’ve stayed up way too late looking through a collection of letters Dad wrote when he was in Army basic training. That was in 1946, after World War II ended. The story we heard growing up, and I’ve got no reason to doubt it, is that he tried to enlist at the outset of the war but was rejected and rated “4F” because he had a punctured eardrum. That condition gradually healed, and he was rated fit to serve and drafted in late 1945 and inducted into the Army in January 1946.

Part of his parents’ legacy that I heard about growing up was a collection of more than 100 letters my grandfather, Sjur Brekke, wrote my grandmother, Otilia Sieverson, during their courtship and early marriage in the first decade of the last century. (The courtship started at a Lutheran parish in Chicago, where he was a visiting minister in training and my grandmother’s family were charter members. Sjur was a smooth operator. We have a note he wrote to Otilia on the back of a business card; the subject was a couple of volumes of commentary on scripture he had “taken the liberty” of loaning her. He also offered to hook her up with more such volumes if she liked the first two.)

Sjur died in 1932, when Dad was 10, and he said his mother not only hung onto all those letters, but read and re-read them. She numbered them and kept each one in its original envelope; she wrote key phrases from each letter on the envelopes, apparently her way of prompting herself as to the contents. When she died in 1975, the letters passed on to my dad. They’re among the papers he left behind. (If you’re wondering about my grandmother’s letters to my grandfather, well, so do we. She destroyed them at some point after he died.)

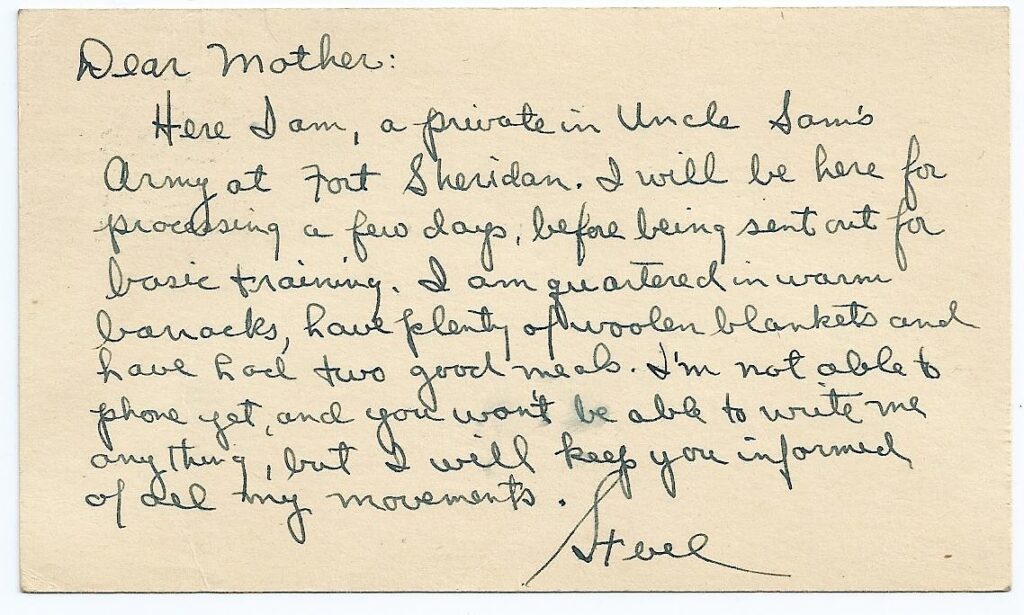

What I didn’t know, though, was that my grandmother kept a second letter archive. She saved all the correspondence Dad wrote during his year-plus in the Army, starting with a postcard from Fort Sheridan, north of Chicago, the day he arrived for processing.

“Dear Mother: Here I am, a private in Uncle Sam’s Army,” he began. I’m guessing the postcard was something the Army had its new inductees do to reassure the home folks they were OK.

There are about 75 of these letters in all — 20 or so from his time in basic training, which took him to Fort Bliss, near El Paso, Texas, and another 50 or so from his time serving in the occupation of Germany.

Leafing through the basic-training letters the other day, I felt like I was getting to know a person about whom I had only heard vague accounts. One thing comes through very clearly: the Army wasn’t really for him. He was interested in learning what he could in the ranks — he was being trained in a field anti-aircraft battery — but he had his own agenda, which always seemed to come back to music and whether he could finagle a way into an Army band (he couldn’t and didn’t). He also loved the opportunity to see a part of the country, dry, desolate West Texas, that was completely new to him.

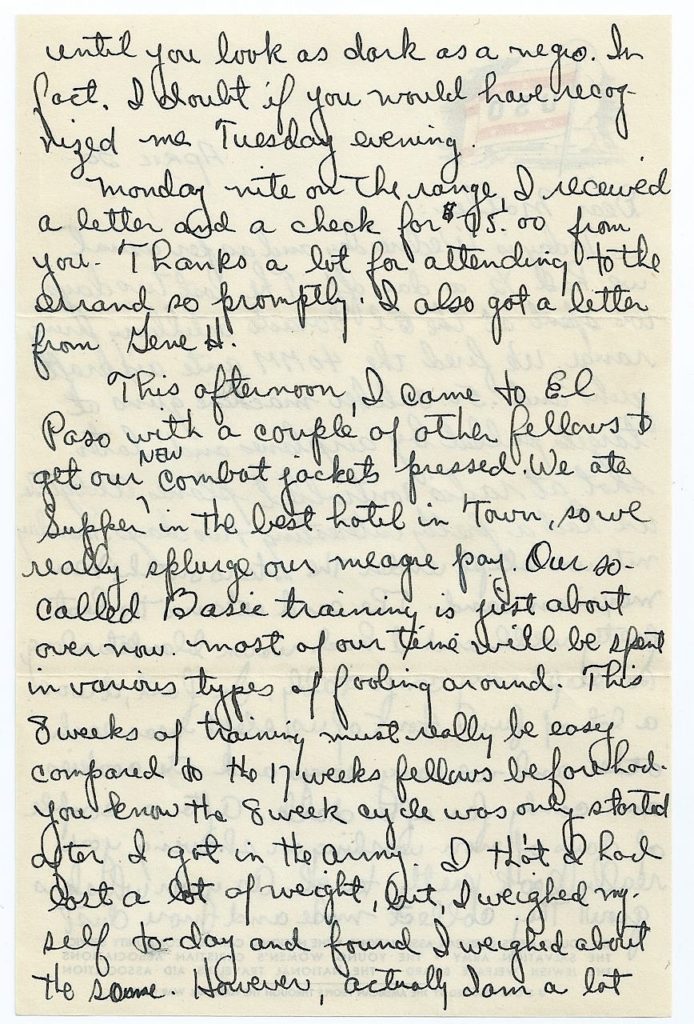

I read a few of the letters aloud the other day to my siblings. One in particular delighted us. Dad describes a trip up to an artillery range to fire anti-aircraft and machine guns at aerial targets. It sounds like he enjoyed that somewhat. But he also liked the chance to camp out:

“Monday nite we slept under the stars on the New Mexican sand. The sand retains the heat pretty well and I had warm blankets along, so slept very comfortably. In fact it was a lot of fun. 4 or 5 of us slept near each other and sang songs and ate cookies and candy far after dark.”

Sounds like a kid at camp. He was also thrilled to go without shaving or bathing and said the grime made him “look as dark as a negro” (of whom there were none in his unit, of course). I’m not sure he ever really had any significant outdoors adventures before this. His parents were older and given to recreations like attending revival meetings. During an extended stay in Los Angeles in the early ’30s, their idea of a Sunday outing was to take Dad to see Amy Semple McPherson preach at her Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

The scan of the full letter is below.