Driving in search of an aspen grove I had read about — more accurately described as a “clone,” a stand of trees generated from a single seed and growing from a single root system — that is alleged to be the world’s most massive organism, I happened across the above, painted on the side of the general store in Koosharem, Utah. That’s about 150 miles south of Salt Lake City and not too awfully far from Interstate 70 (to the north) and Interstate 15 (to the west). Here’s a 2012 image of the same sign, which suggests strongly the piece has been “renewed “over the years.

John Scowcroft and Sons, the Ogden, Utah, firm that made Never Rip Overalls through about 1940, was founded by an English convert to Mormonism who emigrated to Utah in 1880. His commercial endeavors in his new home are reported to have started in the confectionery and bakery business and later expanded into clothing and dry goods.

It’s not clear exactly when Scowcroft and Sons began making “Never Rip Overalls.” ZCMI — Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution, the Utah firm formed in the late 1860s to promote Mormon enterprises and entrepreneurs — marketed “never rip” overalls around the turn of the 20th century, as did a New York-based firm that made Keystone Never Rip Overalls. (And “never rip” was a popular sales claim in this era, as evidenced by the slogan for Ypsilanti Health Underwear: “Never rip and never tear — Ypsilanti Underwear.”)

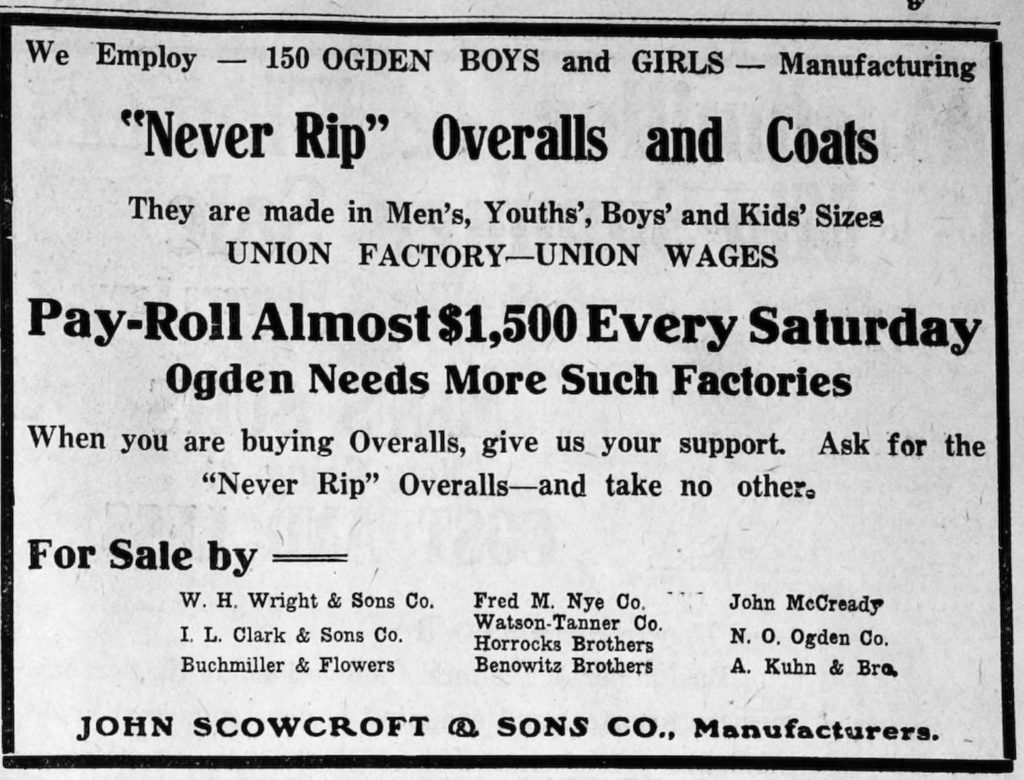

But based on what you find in the newspaper archives it appears that Scowcroft probably started turning out overalls and started a big advertising push for Never Rip Overalls in 1913. The company’s ads touted the clothes’ durability, of course, but put more emphasis on the fact that its products were made in Ogden and that its workers’ salaries supported other local businesses. It claimed a weekly payroll of $1,200 to $1,500 for 150 “boys and girls” (the latter sometimes described as “Utah maids”) who made the goods. Scowcroft also advertised that it was a union shop — apparently organized by the United Garment Workers Union.

Based on those payroll numbers, workers were making an average of $8 to $10 a week. If you figure a 50-hour work week, that would put pay at 16 to 20 cents an hour. Since workers at the plant were paid a piece rate, getting compensated for each item they produced rather than for each hour worked, pay probably varied widely. Scowcroft said in a recruitment ad late in the decade that “girls” were started out at $7.50 a week during training but could earn much more — even $27 a week — once they picked up speed. (One government report from this era suggests a typical work week in the garment industry was more like 55 to 60 hours a week. Average wages ranged from 14 to 40 cents an hour depending on the skill involved in the position and workers’ gender — then as now, female workers were paid less than men working in the same positions.)