I insist I don’t spend a lot of time in cemeteries. But when I do, I’m always conscious of the capsule histories that many grave markers contain. I tend to notice children’s graves a lot, maybe because my brother Mark died at age 2, an event that I remember vividly. Occasionally, you come across what looks like a family story — like the grave we once spotted that is marked as the final resting place of three people named Mary Dahl — a mother and two of her daughters who all shared the name.

During a visit to Chicago several years ago, I went over to Mount Olive Cemetery, where my dad’s parents and many members of his extended family are buried. It’s a beautiful green place in the summer, and you can see that nature will have no problem taking back the property once someone skips mowing the grass for a few years. The older, heavily Scandinavian sections of the cemetery have lots of markers that have shifted askew or fallen, and I always wonder whether there’s any family left to visit these long departed forebears.

On this particular visit, I was stuck by how many graves declared a relationship: father, mother, husband, wife, daughter, son, sister, brother. One of the markers I spotted was unique: “Wife and Baby,” it says. Not “Wife and Daughter” of “Mother and Daughter.” Both had died in 1906, and the child was just five months old. I snapped a picture and later, having taken note of the names and dates, tried to find out what had happened.

I can’t say I found out much beyond the fact that no two people, including the person put in charge of engraving a substantial and expensive headstone, agreed on the spelling of the family name.

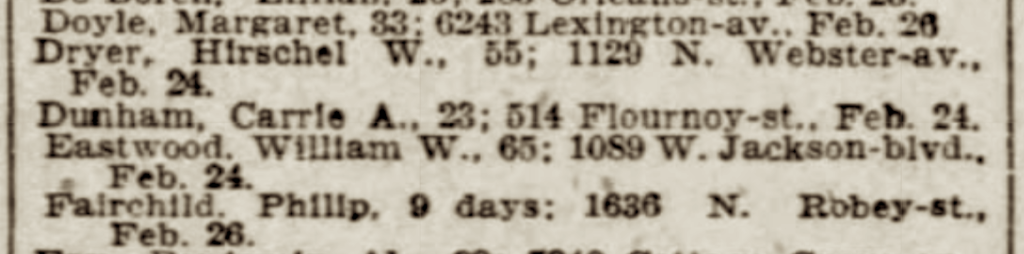

The stone itself says “Dunhom,” as you can see — but that surname doesn’t appear anywhere in genealogical records or in Chicago phone books from this period (though losts of people didn’t have phones in this era). The name used in the “Official Death List” published in the Chicago Tribune several days after Carrie A. “Dunhom” died in February 1906 is “Dunham.” That agrees with a Cook County death index record that lists her full name as Carrie Anderson Dunham and adds that she had been born in Norway in 1883.

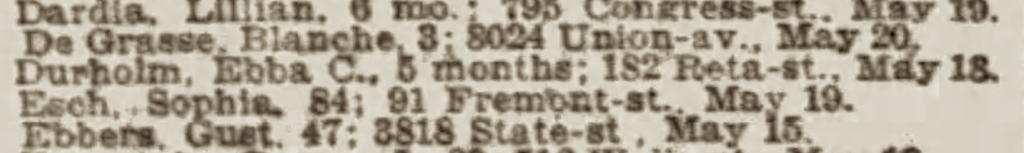

As to Carrie’s daughter, she is listed in the Tribune’s death list as Ebba C. Dunholm. Again, there are no Dunholms or Dunhoms in other records. Again, there’s a Cook County death record that uses the surname Dunham — but lists her given name as Effa. One guesses that there were serial transcription errors that led to all these different renditions of the name. It’s impossible to figure it out without disappearing down some rabbit hole, and I’m not sure you’d be able to sort it out even then.

But I do wonder about the “husband and father” who presumably had this headstone placed. Presumably he had some idea of how he wanted the name spelled. I can’t find any record of him though — no marriage record, no birth record for the daughter. I hope whoever carved the stone rendered it just the way it was handed to him. That, at least, would have been some comfort to the mourner.