Kate and I drove down to Jack London Square for the last Friday night ferry of the year. A low sky, with the cloud ceiling down around the tops of the Bay Bridge suspension towers. Somehow, that made the usual port light show even more intense than (or maybe just different from) usual. Among several ships working in the Port of Oakland tonight, Yang Ming’s YM Great, which arrived this morning is scheduled to sail tomorrow morning.

Rain, If You Look Hard Enough

There it is, that drop of water right there at the end of that little clear holiday lightbulb–evidence of our big New Year’s Weekend rainstorm. Somewhere far to the north, it’s really been coming down the last couple of days. A favorite weather-table wet spot, Red Mound in the southern Oregon Coast Range, has probably picked up half a foot of rain or more. Here, we’re measuring the wet in hundredths of an inch: .01 in San Francisco, .05 on the top of Mount Diablo. Up in the middle of Mendocino County, Boonville got a real soaking: .11. At the north end of the Napa Valley, Mount St. Helena got .16–a full sixth of an inch. And so ends one of the dryest Decembers since the new arrivals in the area started measuring such things a bit more than a century and a half ago.

After this torrent blows through, the next chance that rain will fall within 100 miles of us here in Berkeley is about the middle of next week; and right now, it looks like it might not be much closer than 100 miles.

The Lewis O. Brekke Story, or Documentary Inquiries into The Life of a Non-Relative

While recently pursuing Irresistibly Absorbing Research on the origins of Oakland’s King’s Daughters Home, I happened across a resource that is itself irresistible and absorbing: The Library of Congress’s Chronicling America collection of historic U.S. newspapers. It’s an archive of selected papers published between 1836 and 1922. In doing a quick trace of the history of the King’s Daughters establishment, several stories from the old San Francisco Call, part of the Chronicling America collection, helped fill in blanks.

I went back the next day to see what else might be there. Since I’ve been doing some genealogical research, I thought I’d look at what Minnesota papers might be in the archive. My grandparents lived in several different towns up there in the 1910s and ’20s, and my dad was born in a little town in Marshall County called Alvarado. It so happens that Marshall County still has a weekly paper published in the county seat–the Warren Sheaf. The Sheaf turned out to be one of the papers digitized and included in the Chronicling America archive. I looked for the issue published the week my dad was born, in September 1921, and came across the following in the “Alvarado News” column:

“Born to Rev. and Mrs. S. J. Brekke last Saturday at the Warren City Hospital, a bright baby boy. Congratulations.”

Going through the Sheaf turned up lots of mentions of my grandfather, Sjur Brekke, who was a Lutheran minister and pastor for several Norwegian congregations in the area: in Alvarado (a town of only a few hundred which at the time had a separate Swedish Lutheran congregation with its own minister), in Viking, at a rural church called Kongsvinger, and apparently in at least one other town. Any time something was doing at the churches, the Reverend Brekke got a mention. Every once in a while, my grandmother, Otilia Sieversen, would make print, too–usually when entertaining guests or when off visiting in one of the neighboring towns in Marshall County.

I cast my search net wide, and looked for any mentions of “Brekke” in Minnesota papers in the archive; my grandfather had a brother, Johannes, who lived with his family in the Fergus Falls area around 1920. Johannes was a traveling Lutheran preacher, so I was thinking maybe I’d come across some mention of him. But I didn’t, and since Brekke is not an uncommon name in Minnesota, I got quite a few hits of folks who don’t seem to belong in the family annals. The most remarkable of these involved someone named Lewis Olson Brekke.

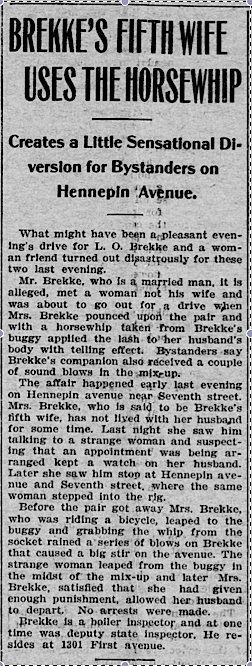

I made his acquaintance in the pages of the St. Paul Globe of Friday, July 10, 1903, under this headline:

Brekke’s Fifth Wife

Uses the Horsewhip

The story, at right above, is a classic police blotter item blown up to separate-item proportions–a marital spat that ends with an ugly scene on a crowded street. The account’s picture of Mrs. Brekke setting upon her cheating spouse with a whip is vivid. But the prize detail for me is, “…Mrs. Brekke, who was riding a bicycle, leaped to the buggy.” She sounds like quite the acrobat.

So that’s that. The unfortunate L.O. Brekke is beaten by his wife, made an object of fun in the local press, and retires to lick his wounds and his pride. Well, no. There’s more to Mr. Brekke’s story. He turns out to have been a sort of running joke for reporters covering the courts in Minneapolis. The year prior to this scuffle, several accounts appeared that detailed a divorce action between Lewis Olson Brekke, the L.O. Brekke of the story above, and his wife, Laura Runbeck Brekke. The Minneapolis Journal reported she had sued for divorce on grounds of “cruel and inhumane treatment” but “could not substantiate her allegations.” Then Lewis sought a divorce on the same grounds, citing his wife’s alleged habit of “throwing various articles of furniture at his head whenever his back is turned.” He said he feared to sleep nights lest Laura attack him, that she called him “vile and indecent names,” and that her ” ‘carryings on’ with a married neighbor had scandalized their acquaintances.” He also claimed he had discovered that she had a common-law husband and thus their marriage was never valid. (In the pages of the Globe, anyway, this way by no means an isolated case. The divorce action featuring the abusive wife appears to have been one of its staples during the turn of the last century. A chance reading of several pages of the Globe finds wives taking swipes at husbands with butcher knives, throwing crockery, wrestling over bicycles, and dumping ice water on their spouse’s heads. And that’s before “Fatal Attraction.” We could have the seeds of a dissertation here.)

It’s not clear how the Brekke divorce suit came out–maybe the stories relating the outcome have not been indexed–but I’m guessing that the “Mrs. Brekke” who resorted to the horsewhip is one and the same as the one who struck fear into her husband’s heart by hurling household objects at him. You’d really like to have a picture of this couple; the best I can do is uncover some of the traces they (and he especially he) left in government documents through the years.

Lewis Olson Brekke, born in Norway, about 1852, emigrated to the United States in the early 1870s, lived in Iowa in the ’70s, in Minnesota in the mid-’80s, then moved to Minneapolis in the early 1890s, and to the Seattle area after 1905 sometime. Lewis was about 50 when accosted by his bike-riding spouse, and Laura Brekke was about 15 years his junior. In the 1900 census, taken in April, she was listed as a servant living in Lewis’s household (the other residents were Lewis’s 13-year-old daughter, whose name was recorded as Ammanda, and three women boarders). Lewis was listed as divorced. Lewis’s and Laura’s relationship bloomed into something else, and they were married in Sepember of that year.

Was she his fifth wife, as the headline says? Maybe. Perusing census and marriage records through FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com–yes, it’s possible to have too many research tools at hand–Lewis shows up in the company of several previous spouses: May (or perhaps Mary) Halvorsen, whom he wed near Decorah, in northwestern Iowa, on December 26, 1874; in an Iowa census taken in 1885, he’s reported as widowed, with three children; later that year, he married a Kari (or Karie or Carrie) Boxengaard in Spring Grove, Minnesota, about 20 miles up the road from Decorah; in September 1893, he married a Phoebe Slocum (she doesn’t sound Scandinavian), in Minneapolis; and then in 1900 we have him tying up with Laura. In later years, he moved to Washington state, and in the 1920 census, nearly 70, he reported himself as married, though no wife was living with him.

As I mentioned before, his divorce and horse-whipping didn’t mark the first time the papers had some fun with him. On Oct. 5, 1892, the St. Paul Globe reported on an apparently fraudulent lawsuit that Lewis had brought against an erstwhile employer:

“The damage case of L.O. Brekke against S.E. Olson & Co. [a Minneapolis “dry goods” store] is over, and the finding of the court is for the defendant. Brekke sued the firm for damages, claiming that while in the firm’s employ he sustained injuries in the store elevator which would render him lame for life. The list of injuries was a long one, as was the number of witnesses who corroborated Brekke’s testimony. The defense introduced evidence from people who lived in Decorah, Io., Brekke’s old home, which proved conclusively that the plaintiff had received the injuries he referred to twenty years ago. He had been lame for the same number of years, and long before he ever dreamed of coming to Minneapolis. Brekke’s divorced wife testified he was lame when she married him long years ago. The case was tried in the United States district court before Judge Nelson.”

A few years later, the Globe dropped in on Lewis as he pursued his duties as deputy state boiler inspector for Hennepin County. He was described as being “considerably incensed” over complaints from residential property owners who felt he was overstepping bounds to “examine every little boiler and toy engine in the city.” Later, he lost out in his bid to be chief boiler inspector for the county, a patronage job.

In various census returns, Lewis listed his occupation as “engineer” or “inventor.” And sure enough, he shows up in the U.S. Patent database for several devices registered over a period of more than 30 years. While he was undergoing his troubles with his soon-to-be horsewhipper, he patented a “folding footboard for iron bedsteads” and apparently started a company to manufacture them. What was the purpose of his innovation? As detailed in the patent application, it sounds like something out of “Seinfeld“:

It is a well known fact that many people object to iron bedsteads simply for the reason that they have no footboard against which the clothes maybe tucked and against which the feet may if desired be pressed. A permanent footboard of the proper dimensions would be objectionable for the reason that the bedclothes could not be thrown over the same in the day time or if so thrown would give to the bed a very awkward and unusual appearance. I believe I have solved the problem in practical and simple manner by providing a footboard which has a folding upper section adapted to be turned flat upon the foot end of the mattress so that the bedclothes may be thrown over the same and the bed given the same made up appearance as if there was no footboard provided. At the same time this folding section may be turned up before a person retires and the bedclothes may then be tucked between the footboard and the mattress. This being done there is nothing objectionable to the bed and the same footboard accommodation is afforded as with an ordinary wooden bedstead.

I don’t find any evidence that Lewis got rich off the revolutionary “swish and swirl” footboard. Or off his other inventions: an improved kerosene lantern, an improved stove and furnace grate, an improved grain-binder, and a draft equalizer (a device to make sure that three-horse teams would plow or pull evenly).

Loose ends I can’t tie up: What happened to those four kids of his? And where did he end up? He had one more turn in court that I can find–testifying in a 1909 death inquest in Washington that he had heard against his drunken landlord threaten to kill his wife shortly before her body was found on nearby railroad tracks. Then there’s the 1920 census, and then nothing–no inventions, no newspaper stories, and apparently no more buggy rides with women friends.

Mission Peak Walk

[Update: Here’s the route for the hike.]

A holiday week outing, down to Fremont, then up Mission Peak. With our trademarked late start, we left home just about 2 p.m. and were on the trail just before 3. A surprise: There was a pretty good crowd setting off the fairly steep fire-road trail toward the peak. The climb is about 2,140 feet, in about 3 miles, from the Stanford Avenue parking lot. The peak elevation is given as 2,517 feet, just a little under the top of Mount Tamalpais (which was visible far to the north above a smoggy-looking haze). I’m used to having trails in our more northerly reaches of the East Bay pretty much to ourselves; meaning sure, you see other walkers, but generally they’re some space between groups. One exception to that: Nimitz Way in Tilden Park, above Berkeley, which has a large parking lot that generally seems mobbed on the weekends (the main reason, along with the asphalt paving, I haven’t walked out there in years). But I think the crowds are drawn to the Nimitz Trail because it’s easy, whereas the Fremont Peak walk involves a pretty decent grade most of the way (for my knees, easier up than down).

The day was warm and the light was gorgeous all the way up. The mountain gets rockier and more “alpine”-feeling the higher you go. We got to the top just after sunset, and I had the thought as several groups passed us on the way down that maybe we’d be the last ones up there for the day. We hung out for a few minutes, took some pictures, at sandwiches that Kate had made, gave the dog some water, broke out a headlight to negotiate the rocky parts of the trail in the dusk, then started down. And here came another surprise: hikers, alone and in small groups, climbing up the trail in the dark. We stopped one group of three to ask whether this was a local custom. It is. Since the park is open until 10 p.m., this is a popular destination at night; and that’s a big difference from the Berkeley Hills, where the parks seem to clear out completely at dusk even though they’re technically still open as late as the ones further south.

The picture above: Looking west from Mission Peak across southern San Francisco Bay. The light really was that good, only better.

Holiday Greetings from the Exterminators

From my brother John, in New York.

First of All Martyrs, King of All Birds

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds,

St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze,

Although he was little his honour was great,

Jump up me lads and give him a treat.

—”The Wren“

Of course, in Ireland and like parts, the “king of all birds” was singled out for some rough treatment the day after Christmas. A somewhat sanitized version of the song, on The Chieftain’s “Bells of Dublin” album, alludes to the death of the wren, but doesn’t explain how it came to expire. Liam Clancy’s much earlier recording of a traditional number, “The Wran Song,” doesn’t leave much doubt about what had happened to the bird: “I met a wren upon the wall/Up with me wattle and knocked him down.” In fact, if you’re inclined to explore further the Irish (and fellow Celts’) Christmastime wren customs, here’s a book for you, “Hunting the Wren: Transformation of Bird to Symbol.”

A brief passage on the traditions of the wren hunt: “Typically, on the appointed ‘wren day’ a group of boys and men went out armed with sticks, beating the hedges from both sides and throwing clubs or other objects at the wren whenever it appeared. Eyewitnesses described the hunting of the wren in Ireland in the 1840s:

For some weeks preceding Christmas, crowds of village boys may be seen peering into hedges in search of the tiny wren; and when one is discovered the whole assemble and give eager chase to, until they have slain the little bird. In the hunt the utmost excitement prevails, shouting, screeching, and rushing; all sorts of missiles are flung at the puny mark and not infrequently they light upon the head of some less innocent being. From bush to bush, from hedge to hedge is the wren pursued and bagged with as much pride and pleasure as the cock of the woods by more ambitious sportsmen.”

And why is the wren “the king”? According to the book above, the appellation goes back to a fable apparently current in several cultures and in Greece and Roman tradition ascribed to Aesop: various birds vied with the eagle for the title of the king of birds. One by one, the eagle out-soared them. But the wren–the wren concealed itself in the eagle’s feathers, and as it sensed the eagle was tiring, flew up and away, farther than the eagle could reach.

But enough of the wren. I really want to talk about December 26, also known as Boxing Day (what’s that about? Here’s a rather tart view from early 19th century London) and St. Stephen’s Day. The latter is of special note for me, since my dad’s first name, and mine, are Stephen. A few years ago, my friend Pete offered up a find from an encyclopedia on Roman Catholicism on the life and times of St. Stephen, who is remembered as the first Christian martyr. The capsule version of his trouble is recounted in the New Testament book of Acts. Therein, it’s recorded that locals in the Greater Holy Land area didn’t appreciate everything Stephen, whom Jesus’s apostles had appointed a deacon and put in charge of distributing alms to poorer members of the community, had to say on theological matters. He was accused of blasphemy, hauled before the Local Religious Tribunal, and tried. During the trial, he continued to outrage his accusers, whereupon, according to Acts 8:

“…They were cut to the heart: and they gnashed with their teeth at him. But he, being full of the Holy Ghost, looking up steadfastly to heaven, saw the glory of God and Jesus standing on the right hand of God. And he said: Behold, I see the heavens opened and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God. And they, crying out with a loud voice, stopped their ears and with one accord ran violently upon him. And casting him forth without the city, they stoned him. And the witnesses laid down their garments at the feet of a young man, whose name was Saul. And they stoned Stephen, invoking and saying: Lord Jesus, receive my spirit. And falling on his knees, he cried with a loud voice, saying: Lord, lay not this sin to their charge: And when he had said this, he fell asleep in the Lord….”

A few years ago, I was in Paris and after wandering through the Latin Quarter and up toward the Pantheon, landed in front of a church where the denouement of this story is depicted above the entrance. I only slowly put the name of the church, St. Etienne du Mont, together with the story of St. Stephen (Stephen=Etienne en français). I stand by my earlier description of the scene (picture below): “Immediately above the doorway … Stephen is about to earn his way onto the church calendar despite the presence of an angel who, though appearing benificent, doesn’t seem the least inclined to stay the hands of a bunch of guys who look not at all hesitant to cast the first stone.” One detail of this image I didn’t notice before: The sculpture was done in 1863, a good 240 years after the church was dedicated.

Boxing Day: A Critique

While perusing the Grand World Treasury of Digital Distractions for “information” about the various observances that take place December 26–including England’s Boxing Day–I happened across the following. It’s from the December 31, 1825, number of The Portfolio, a London magazine “Comprising the Wonders of Art and Nature, Extraordinary Particulars Connected with Poetry, Painting, Music, HIstory, Voyages & Travels.”

BOXING DAY

At length the long-anticipated and wished-for day arrives; all classes from the merchants clerk down to the parish Geoffrey Muffincap, are on the tip-toe of expectation. Many and various are the ways of soliciting a Cristmas [sic] gift. The clerk, with respectful demeanour and simpering face, pays his principal the compliments of the season, and the hint is taken; the shopman solicits a holiday, in full expectation of the usual gift accompanying the consent; the beadle, dustmen, watchmen, milkmen, pot-boys &c. all ask in plain terms for a Christmas-box, and will not easily take a refusal; crowds of little boys are seen thronging the streets at an early hour with rolleu papers in their hands, these are specimens of their talent in penmanship, which they attempt to exhibit in every house in their respective parishes; four or five of these candidates for a “box” are seen collected together to watch the success of one, who, bolder than the rest, has ventured first to try his luck. Woe to the tradesman who gives his mite: a hundred applications are sure to succeed a successful one, and what with their hindering the usual business of their shop, and their importunities to shew their “pieces” the poor man has no peace of his life. The money obtained in this way is generally expended the same evening at some of the theatres. It is truly amusing to trace the progress of boxing-day with the generality of those who go from ddorto door collecting this customary largess.— To illustrate this I subjoin a short journal of the day’s proceeding written by one of these gentry and forwarded to his father in the country.

BOXING-DAY

“Got up at 7 o clock—quite dark—struck a light, and cleaned my master’s shoes; while I was about it, thought I might as well clean mistress’s and little master’s—mistress gave me 5s. last year. Mary, the maid, offered to take mistress’s shoes up to her—would not let her—told her they were not finished, meant to take them up myself. Breakfasted at half past eight—could not eat much—went up stairs to ask the governor for a day’s holiday, he grumbled, but gave me leave to go—put his hand in his waistcoat pocket—expected 5s. at least—all expectation,—he drew out his hand and with it his pen knife. I looked very foolish and felt my face as hot as fire—wished him a merry Christmas; thanked me, gave me half-a-crown, and said times were very bad—thanked him and went to fetch my mistress’s shoes up; she gave me nothing; she may do them herself another time.—Dressed myself and went out a boxing—first to Mr. Scragg’s the butcher—he told me master had not yet paid his Christmas bill—no go—went next to the bakers; got 6s. collected altogether £2. 12s.—called on Sam Groomly—went together to Pimlico, I stood treat at dinner; parted from him; and at about a quarter past four got to my dear Sally’s to tea—took her and her sister to the Olympic—a very fine place—saw them home, and promised Sal to go and see her on twelfth day night. Got back to my lodging about half past twelve with 3s. 2½d. in my pocket—spent a great deal: but Christmas is but once a year.”

This, like many other of our ancient customs, is much abused, and is made the vehicle for much annoyance; yet at the same time so much has been done towards depriving the lower classes of their amusements, that we cannot wonder at their making the most of those that remain.

J.W.F.B.

Luminaria 2011: The Lights

A shot across the street from our place, looking north on Holly toward and beyond Buena Avenue. A capsule summary: the lights seemed to stretch farther than ever tonight, and neighbors to the east of us shut down a block and had a communal dinner in the middle of the street. Lots of people were out walking, and lots of the walkers stopped by the table in front of our place for cider and baked stuff and stayed to talk. A special night. And a special day to come for all, I hope. Merry Christmas.

Luminaria 2011: The Cider

Luminaria 2011: Before the Lights

The neighborhood’s getting ready for tonight (“tonight” being this). Dozens of people over at our neighbor Betsey’s house, around the corner, getting luminaria bags and dispatching them via wagon and wheelbarrow all over the neighborhood. It’s still a surprising and amazing spectacle, even after seeing it year after year. (Pictured above: corner of Buena Avenue and California Street).

More later.