In October 2022, I took a driving trip that took me to Salt Lake City, Moab, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, among other stops. I took U.S. 6 between Salt Lake and Moab. The route heads south and east and along one stretch descends through a striking piece of landscape called Price Canyon. At its southern end, the canyon levels off and widens into a valley, where you’ll find the town of Helper. I stopped at the outskirts, walked around a little, and took a few pictures. I posted one to Facebook, and a friend who commented asked where the name of the town came from. Never one to let the opportunity for a bit of research pass me by, here was my answer:

Hi: I took note of your comment on Facebook wondering where Helper, Utah, got its name. It turns out not to be a super-long story, unless I can turn it into one.

The short version is this: The town started out as a small settlement at the point where a rugged piece of western topography called Price Canyon (and the Price River that flows through it) open into a little valley where Teancum Pratt, the hard-luck son of one of Utah’s Mormon pioneers, settled around 1881. About the same time as Pratt’s arrival (with his two wives and seven children; eventually he and his wives had 17 children, and he did prison time for his plural marriage), the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad, was laying out a route down Price Canyon. Trains traveling up the canyon — to the northwest, toward Salt Lake City — faced a long grade, about 1,700 feet in 15 miles. The railroad chose a site near Pratt’s new homestead for a station where it would position extra locomotives — “helper” engines — to enable Salt Lake-bound trains to make it up the canyon. So there it is. “Helper” became the name of the community that grew up around the station. I think it’s at least as good as “Prattville.”

When I drove through there, what I noticed was the spectacular route through the canyon and the striking cliffs surrounding the town (along with the sign of the Balance Rock Motel). It’s almost too much to slow down enough and contemplate how the world we’re moving through was shaped. When I manage to do that, I’m always surprised and often pleased in a way by what I find.

For instance, this guy Teancum Pratt. There seem to be lots of little capsule histories that name him in reference to Helper, but none that mention much of his personal experience. I describe him as “hard luck” after reading just a little of his journal. Among the episodes he describes in narrating his life before Helper, here’s one from his teens:

“In my 15th year, I had the misfortune to lose half of my left foot, which was frozen off while working for George Higginson. I was driving a freight team of 2 yoke of cattle. It was winter. We made it to Salt Lake City before Christmas. Mr. Higginson sent me on to Lehi Fields with both teams of cattle. This took me all day and night, and by morning I was frozen badly. Mr. Higginson treated me badly, being fed on bread alone and not enough of that.”

And here’s a summary of events just before he dragged his clan to what would become Helper:

“I found that my physical strength was not sufficient to endure hard labor and about the last of June, 1880, I came to the conclusion that I would go out to the frontier and take up land and either sink or swim in the attempt to maintain ourselves. So hearing of Castle Valley, I struck out and came to Price River on the 24th of July, 1880, coming down Gordon Creek from Pleasant Valley and locating at the mouth of Gordon Creek. But the neighbors were hunters, trappers, and bachelors, and soreheads and did not welcome any settlers, so I had a very tough time of it and had to leave that location and moved up to what is now Helper, at that time a lovely wilderness, and commenced anew in 1881.”

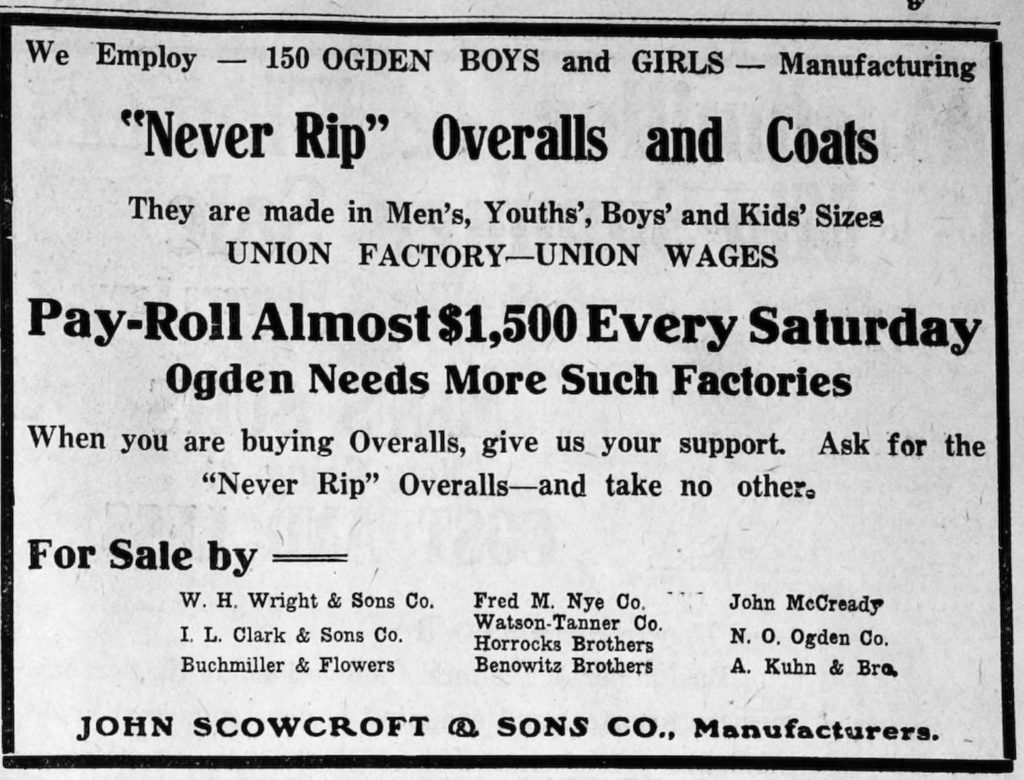

Pratt found that the land he had settled wasn’t particularly fertile, and among the various ventures he embarked upon was coal mining. Coal is still a big deal in that area of Utah — Helper is located in Carbon County, which is still a major producer (and has been involved in recent years in trying to build a coal port in Oakland). Mining drew lots of people, money and union organizing to Helper and environs.

And crime, too: In 1897, just up the canyon from Helper, Butch Cassidy and associates managed to hold up the payroll manager of one of the coal companies who had come down on the train from Salt Lake City to pay miners.

And of course, all that just barely scratches the surface of the past of this one place. What transpired here before the “settlers” wandered in? Maybe I’ll get to that.

Conclusion of seminar. Hope all’s well with you as autumn draws on. …