Like everyone else who’s walking around with one of these “phones” equipped with a high-quality camera (or are they really decent cameras with mediocre-quality phones?), I take lots of pictures. Sometimes I try to discover a theme in what attracts my attention, but aside from “landscapes” or “birds” or “infrastructure” or “stuff on the street,” I would struggle to name any real thread that ties any of my images together.

But a couple of days ago I was looking a few pictures — just three — I had taken on three separate trips to other parts of California over the last few years and was surprised to see something of a story there.

Here are the images:

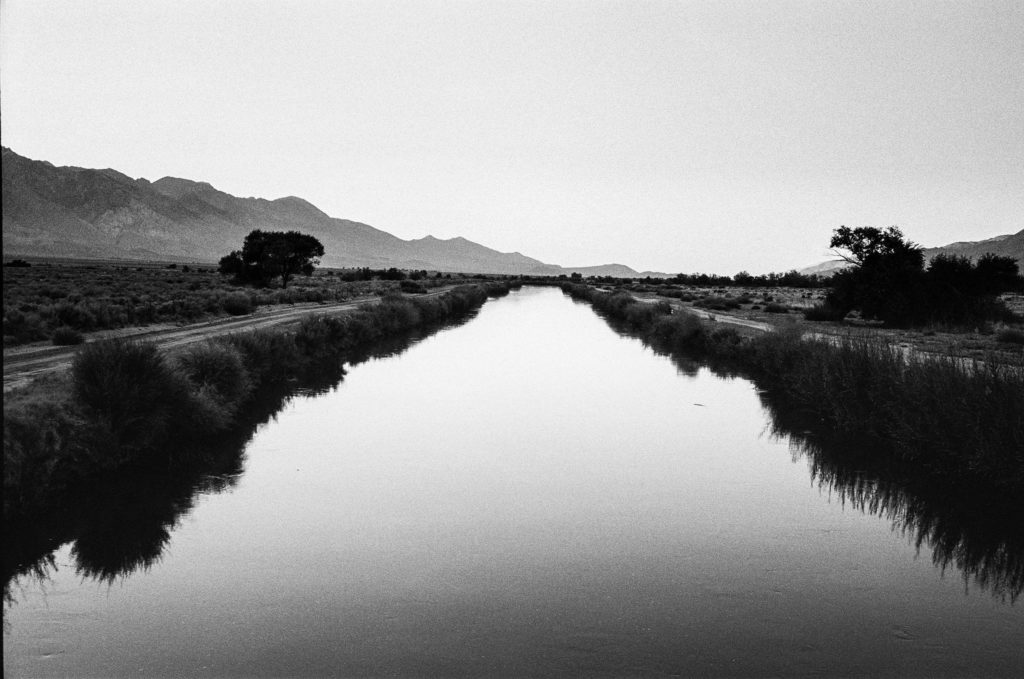

That first shot is the Los Angeles Aqueduct, in the Owens Valley just across the highway from Manzanar, the site of the internment camp where thousands of Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. Kate and I camped nearby, just outside the town of Independence, in 2018. After spending a beautiful September afternoon touring Manzanar, we wandered down to the aqueduct as the sun was setting.

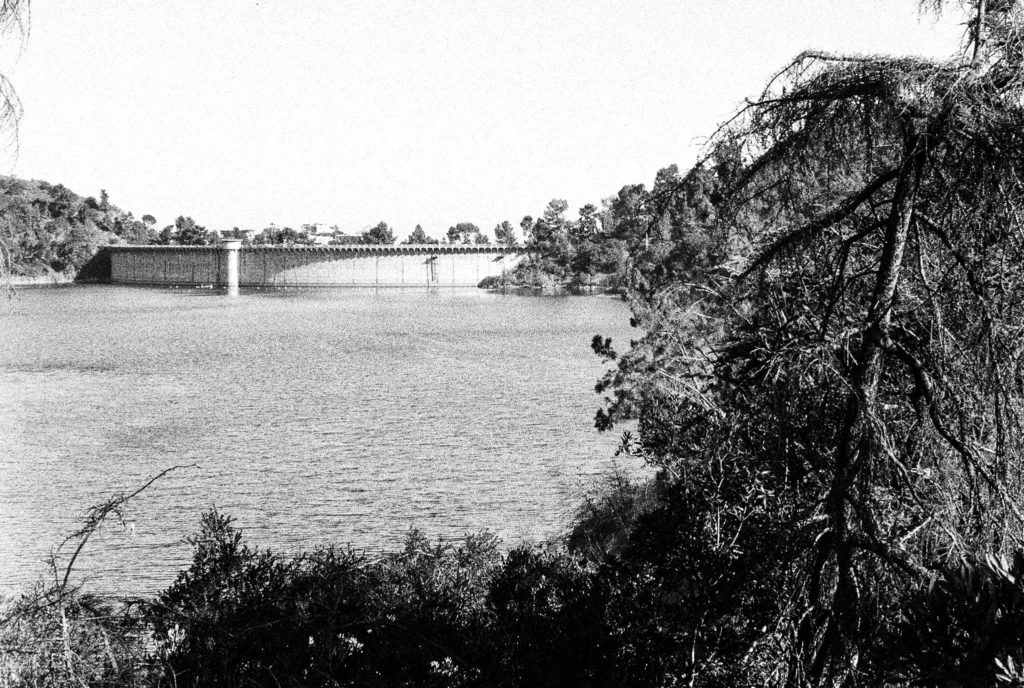

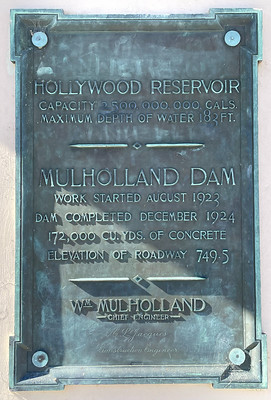

The second shot is the Hollywood Reservoir and Mulholland Dam in Los Angeles. I had wanted to see this place for years, and we made it up on a Sunday afternoon last June while visiting our son Thom.

The third shot shows part of the wreckage of the St. Francis Dam, in San Francisquito Canyon, in northwestern Los Angeles County. The dam collapsed in March 1928, killing about 450 people downstream. You have to hunt a little for the site of the dam, which Kate and I did on the same 2018 trip that took us to Manzanar.

I like the fact all three images were shot on film using relatively antique (1970s-era) Japanese rangefinder cameras. But what ties them together, perhaps obviously, is the connection to Los Angeles, water, and L.A. Department of Water and Power chief William Mulholland.

Mulholland was the principal architect of the Los Angeles water system: He played a leading role in helping secure (or steal, depending on your perspective) the Owens Valley water rights for the city. He engineered the aqueduct that brought the water to Los Angeles. Although he was initially reluctant to build dams and reservoirs to store that water, he designed and supervised the construction of Mulholland Dam, which took all of 16 months to complete in 1923-24. He used that structure as a sort of template for the St. Francis Dam, which was completed in 1926. Mulholland visited St. Francis Dam just hours before it disintegrated and pronounced it sound; the catastrophe ended his career. Although he apparently believed Owens Valley saboteurs were responsible, as they had been for the destruction of some of the aqueduct facilities in the eastern Sierra, he took public responsibility for the tragedy. “Don’t blame anybody else,” he told a coroner’s inquest. “You just fasten it on me. If there is an error of human judgment, I was the human.”

As I say, I just happened to look at the three photographs together the other day and see a story. If I ever have a show, I thought, I’d want to present them as a group. For some reason, I thought a presentation like that would be more complete with a fourth image. I remembered a 2017 visit to Los Angeles during which we stopped at the Department of Water and Power building (a.k.a. the John Ferraro Building), at the corner of First and Hope streets, and just across the way from the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the former home of the Oscars.

I took some pictures when we were at the DWP building — all with a digital SLR, not film. Looking back, I found one that I thought I could add to the group — post-processed from color to black and white. It’s looking up from a corner of the building up toward the roof, with the sun just obscured:

What kind of statement is that making? I haven’t come up with words yet, though I like the image. And as I say, if there ever is a show, this one’s going in.