The way I remember it is I was home from school — I was a fifth-grader at Talala School in Park Forest, in Chicago’s south suburbs. I’m sure I was bored and looking for something to do — I wasn’t that sick. I was as interested in politics as any fifth-grader — well, not counting my former classmate Billy Houlihan, whose father, John J. Houlihan, was getting ready to run for the Illinois House of Representatives (he won and wound up serving four terms). I’ve forgotten my specific motivation on the long-ago day in question, but I sat down and wrote a letter to Otto Kerner, who had recently begun his second term as governor, congratulating him on his victory and asking for an autographed picture.

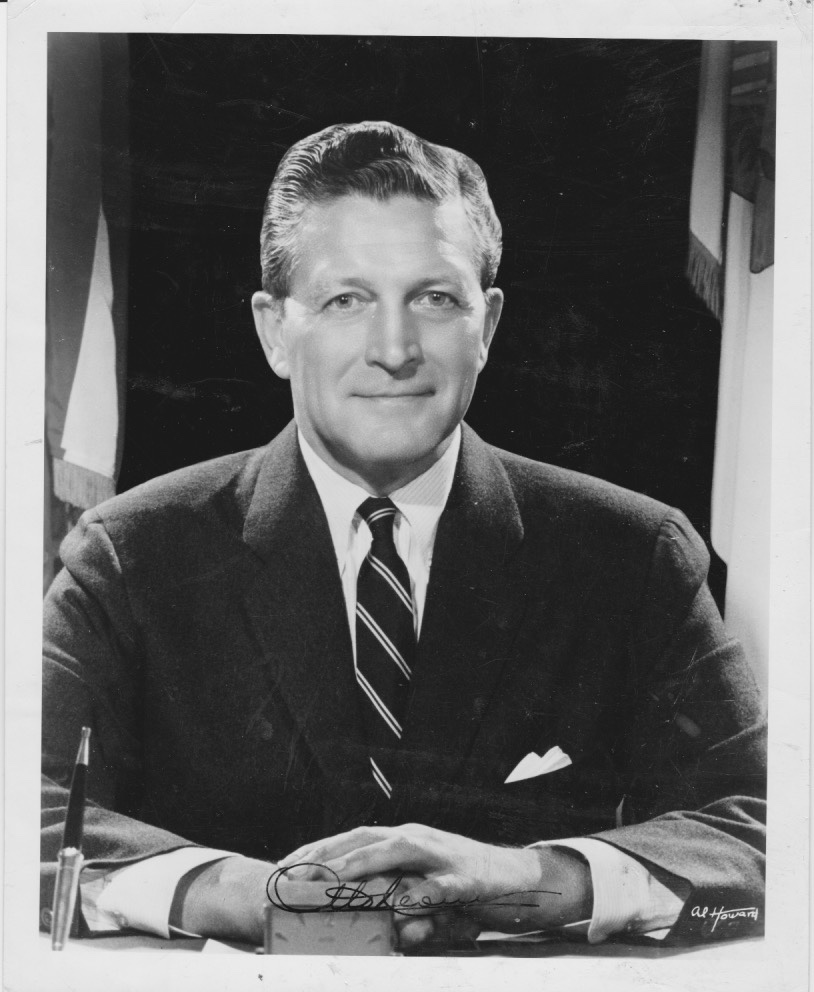

The portrait above, with a short letter acknowledging my note, arrived a week or two or three later. I was inspired, and a hobby of sorts was born. I started writing to other politicians who were in the news: Edward Brooke, the Republican Massachusetts attorney general who became the first popularly elected Black U.S. senator and the first to serve in the Senate since Reconstruction; Pat Brown, the Democratic governor of California; Nelson Rockefeller, the “liberal” Republican governor of New York.

Soon, I started going down the list of members of the U.S. Senate. The notes I sent were brief and to the point, written in my imperfect Palmer method cursive on a sheet of blue-lined notebook paper: “May I please have an autograph of Governor X or Senator Y?” — not much more than that. I was pretty unaware of the politics of a lot of the senators whose portraits I was requesting. So I sent away for pictures of Richard B. Russell of Georgia and John McClellan of Arkansas, two of the staunchest segregationists in “the world’s greatest deliberative body.” (Robert Caro’s “Master of the Senate,” the third volume of his biography of Lyndon Johnson, is an effective antidote to that “greatest deliberative body” nonsense.) But I also wrote to Bobby Kennedy’s and Gene McCarthy’s offices.

After collecting about 60 or 70 of these signed pictures, I got bored with the project. I was still passionately interested in what was happening in politics — in the Civil Rights and anti-war movements, especially — but the interest took other forms: going with my mother to the weekly peace vigil at the post office in Park Forest, for instance.

What is there to remember about the man in this particular portrait?

Kerner became a national figure in 1967 when President Johnson appointed him to lead a commission studying the causes of the widespread riots of that summer — the ones that always come to mind were in Detroit and Newark. The resulting report unflinchingly concluded that the nation’s long history of white racism, oppression and abuse of Black people drove the 1967 uprisings. (“What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”)

The report was a little too unflinching for Johnson’s taste, and he declined to publicly endorse its conclusions or support its call for a sweeping program of investments to address the effects of past discrimination.

Still, before Kerner’s second term as governor was over, Johnson nominated him to serve on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. But Kerner’s undoing was not long in coming: He was indicted in 1972 for conspiracy, income tax evasion, mail fraud and perjury. The indictment said that early in his first term, he had agreed to set favorable racing dates for a Chicago-area horse track in exchange for stock in the track, which he later sold at a significant profit. Kerner was convicted on 17 counts. On appeal, all but four of the counts, all for mail fraud, were thrown out. But he was sentenced to three years in prison — a sentence that was cut short by the discovery he was suffering from lung cancer. He died in May 1976.

Kerner’s New York Times obit mentions that some supporters never believed he was guilty, and many others remained sympathetic to him after his fall. A few months before Kerner died, the Times reported, “Chicago journalists organized a ‘newsmen’s testimonial dinner to Otto Kerner.'”

“‘We like the guy personally, no matter what he’s done, and we thought it would be a shame if someone didn’t do something for him,’ said Steve Schickel, a television reporter for station WLS-TV. “