Fifty years ago today, I started my first newsroom job.

But wait a second. Let me set the stage first.

I had graduated from high school a semester early. I was inspired in part by a friend whose desperation to get out of school drove him to take a bunch of classes early and graduate a full year ahead of us in the Crete-Monee Class of 1972.

Getting out four months ahead of my remaining classmates seemed as close as I was going to get to any kind of high school accomplishment. I was as average as average could be gradewise, the result of doing occasionally brilliantly in English and history classes and barely achieving passing grades in math and science. I believe I ranked 158th among the 314 students who graduated in ’72, which I joked made me the valedictorian of the bottom half of the class.

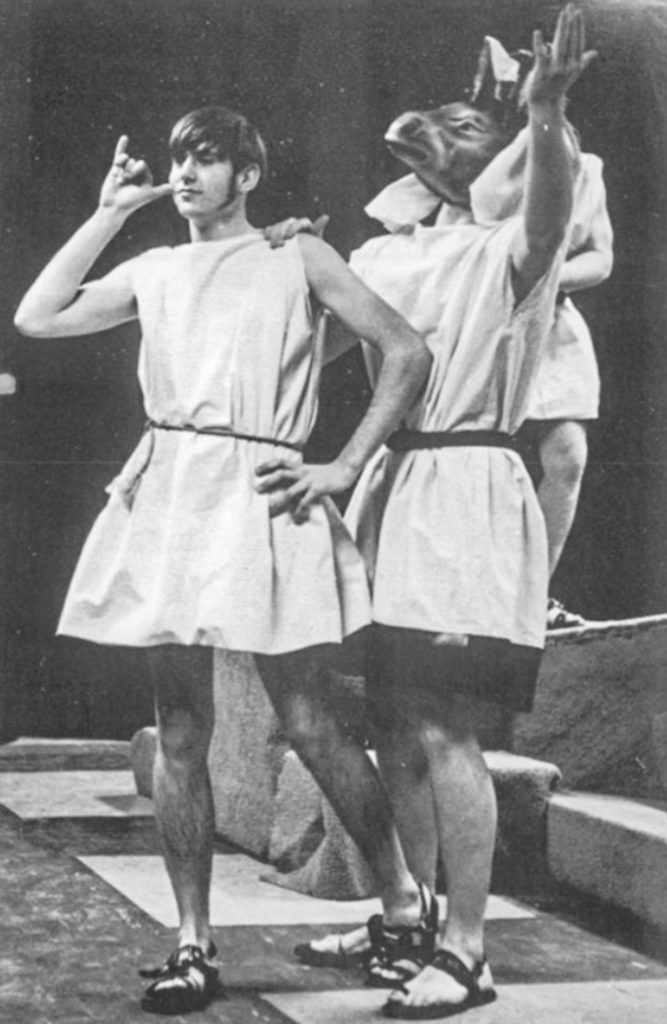

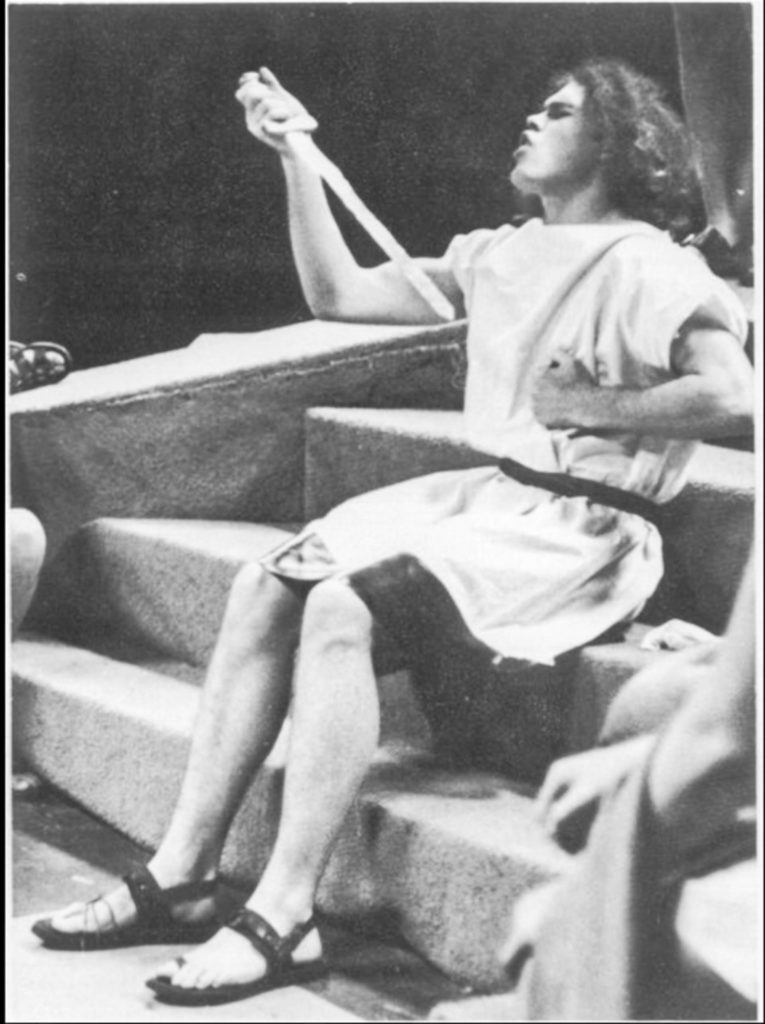

And I did get what I considered a valedictory moment: My final semester at Crete, I took a drama class with a teacher named Tommy Thompson. He told me a few weeks into the class that he had a part for me in the school play, which would be put on in January, just before I was done with school. The part turned out to be Nick Bottom, the bombastic fool who’s transformed into an ass in “A Midsummer NIght’s Dream.”

So this was January 1972. I didn’t have a plan laid out beyond a position I had staked out a couple years earlier that I didn’t want to go right from high school to college. It wasn’t clear what this non-college period would look like beyond getting together with friends and smoking whatever it was popular to smoke, but I eventually had one idea about that.

We lived in a sort of rural, informal, woodsy subdivision — this was about 35 miles south of downtown Chicago — and among our neighbors out there were the McCrohons — Max, an Australian immigrant, his wife Nancy, an immigrant from Westchester County, New York, and their kids Sean, Craig and Regan.

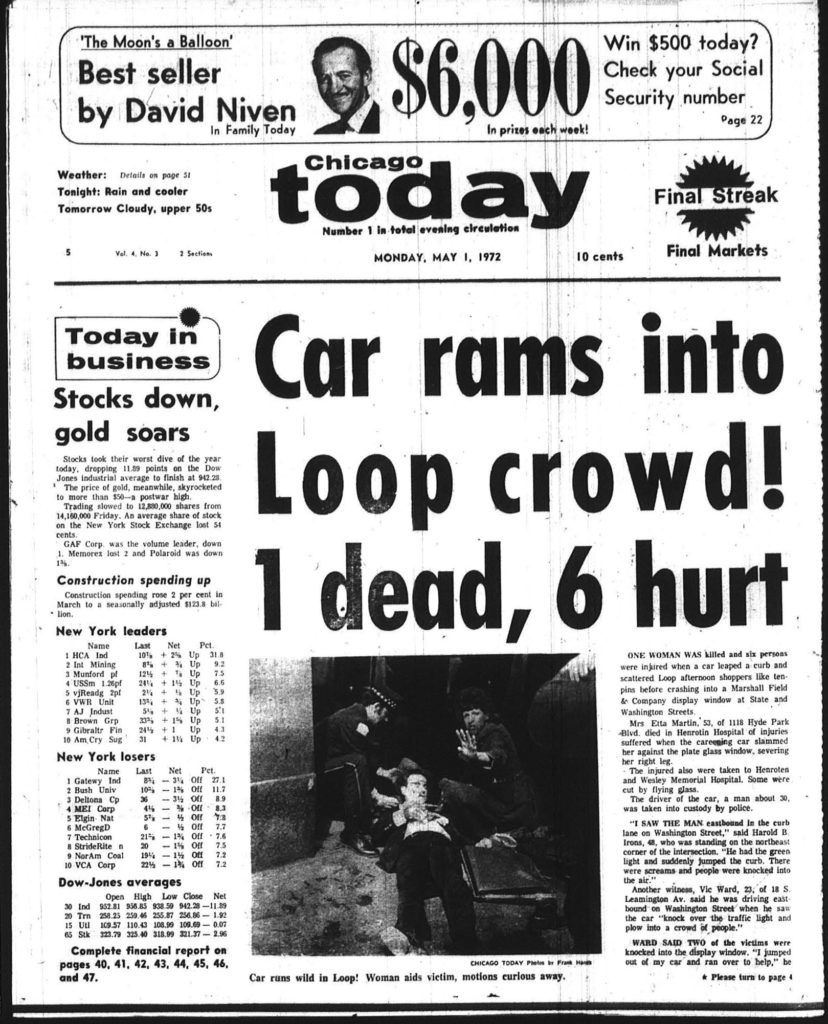

Max was a newspaperman. He’d first come to the United States in the early 1950s as a reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald. By the time our families met, in the mid-1960s, he was an editor at the Chicago American (a former Hearst paper that the Chicago Tribune had bought and rechristened “Chicago’s American.” But I digress.) In 1969, Max was one of the editors who led the redesign and relaunch of the paper as Chicago Today.

My family was always engaged with the news. For most of my time growing up, I think we got two papers a day — the Tribune, and later the Sun-Times, in the morning, and the Daily News, and later Chicago Today, in the afternoon. We watched the early evening news, national and local, and then the late news. There was no NPR back then, but we would have been listening to that all the time, too, probably.

And “news” just wasn’t whatever happened to be in the papers or on the national and local TV news. For me, the stories that at least in my memory were woven into our daily lives all grew out of the the civil rights struggle and the Vietnam War.

As I wrote a while back, Max and Nancy McCrohon were always welcoming to my brothers, my sister and me. They indulged my presence for hours at a time on weekday nights, where often we’d talk about what was in the papers that day. They’d invite me to stay for dinner, and though it was less than half a mile back home, Max would insist on driving me at the end of the evening.

By the time I was done with high school, Max had been appointed the Tribune’s managing editor, the same position he held at Today. One night when I was over and we were watching the 10 o’clock news, we were talking about what I was going to do now that I had graduated. I don’t remember the particulars, really — the only thing I feel reasonably sure about is that I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do — but I think I asked him what it would take to work at one of the papers. And that’s how the idea of applying for a job as a copy boy at Chicago Today came about. It was a sort of prized entry-level position, and he said he could get my name “shuffled to the top of the list” of candidates.

That was in February ’72, maybe. A couple of months later, probably, I got a call asking if I could start May 1. Yes. I could and I would.

I wish I had a picture of 18-year-old me on that first day. I don’t remember a lot of details. I got to take the Illinois Central — the I.C. — from Richton Park, our station at the southern end of the commuter line, up to the last stop downtown, Randolph Street. The best exit was the one out onto East South Water Street. From there, it was about a five-minute walk to Tribune Tower, where Chicago Today shared space with its parent paper. There were two entrances — the grand one at 435 N. Michigan Avenue, and the more modest one next door at 445 N. Michigan that Today employees used. The newsroom was on the fourth or fifth floor.

I had the same long hair that I had sported in my “Midsummer Night’s Dream” performance, but for some reason, I thought it would be more dressy or neat or something to wear it in a pony tail, which I could just barely get my unruly mop into. I also wore a pair of corduroys held up by some braided leather suspenders my girlfriend had made. I must have cut quite a figure as I walked into the city room for the first time. I don’t remember whether someone said something or I just saw a couple of smirks, but I reconsidered my style, and the pony tail and the suspenders were retired after the first day.

What did that first newsroom job involve? Well, the term “copy boy” has been retired, too, but basically, you were there to run any kind of errand the reporters or editors or front office secretaries needed. Heading down to the mailroom to get the edition that was just coming off the press. Getting coffee and making sure you remembered just how every editor on the news and copy and city desks liked theirs. Getting lunch for said editors — the most memorable purveyor of which was a basement dive about a block from the paper called The St. Louis Browns Fan Club, whose specialty was a really greasy cheeseburger. I’d be painting less than a complete picture if I left out the shouting and swearing and other indecorous behavior that you’d encounter on at least a daily basis.

None of that sounds like it has much to do with news. Here’s the part that did.

On deadline, our job was to run the typed copy from reporters to the city, copy and news desks. Depending on the shift, there would be somewhere between three and six rewrite men — and they were all men — taking dictation from reporters somewhere out there in the city. They’d write their stories one paragraph at a time on a tissue-thin sheet of paper backed by four carbon copies (also tissue thin). When a paragraph was finished, the rewrite guy would pull it out of his typewriter and call (usually shout): “Boy! Copy!” Or “Copy!” Or “Copy boy!”

Whereupon you’d hurry to the grab the copy and separate the top sheet from the carbons as you walked to the city, news and copy desks, which were clustered at the center of the city room. You’d give the top sheet to the city desk, and the other desk would each get one of the carbons. On edition, that routine could keep you busy.

One of the other jobs we did was watching the wire room, the semi-sound-proofed space where all the wire service teletype machines were spitting out stories from all over the world. If you were assigned to the wire room, you’d separate each new story as it came off the machine, then run it to the desk editor who needed to see it. You also had to make sure the teletypes didn’t run out of paper — the big rolls (which also included carbons) that ran through the machines hour after hour all day and all night long.

Of course, that’s all stuff I had yet to discover on that first day, which was spent “learning the ropes” — how to get down to the mail room and the composing room, say — and filling out paperwork, and maybe hearing about which reporters and editors you had to watch out for.

Fifty years later, and I’m still working in a newsroom — or at least for a newsroom, given pandemic realities. I have thought a lot about what it means to have been lucky enough to get to do this work for so long — not all of the last 50 years have been spent in news, but nearly all of that time was what people might now call “news adjacent.”

I’ve thought a lot about that half century as this day approached. About the technological changes. About all the changes in perception of what news is and what facts are. About the shortcomings of journalism and its triumphs. About the changes in who gets to do the work — it’s very clear in my memory that the Chicago Today newsroom I walked into was all white; there were just two women working in the department as I recall it — and about how much further those changes have yet to go. About all the people I’ve worked alongside. About how we treat each other in the news business. About my own failings. And even about my successes, such as they are.

I’ve thought a lot about all of that, and yet, you know, it takes me a while to gather myself for the challenge of writing about some of it. But yeah, maybe, sometime during this 50th anniversary year that will happen.

For now, I’ll sign off with something I didn’t remember from that first day at work.

You can see our early edition headline at the top of the column here. I have to say, without having read the story in question, that it must have been a really slow news day for a “doctor shortage” to become the lead story in a big-city tabloid.

What I’d forgotten before I spent an afternoon last summer spooling through microfilm at the Chicago Public Library was how the front page evolved that day.

The lead in the next edition was “Lift wage, price curbs for millions,” which is another yawner.

Then something happened less than a mile away in downtown Chicago. Our next-to-last edition, the Green Streak, bannered: “Car rams crowd in Loop, 6 injured!” Yes, there was an exclamation point — it appears to have been a Chicago Today specialty.

The story detailed an incident where a car jumped a curb at State and Washington streets and crashed through one of the display windows at Marshall Fields. It was clear people were hurt.

The story evolved rapidly. The last edition, the Final Streak, is below.