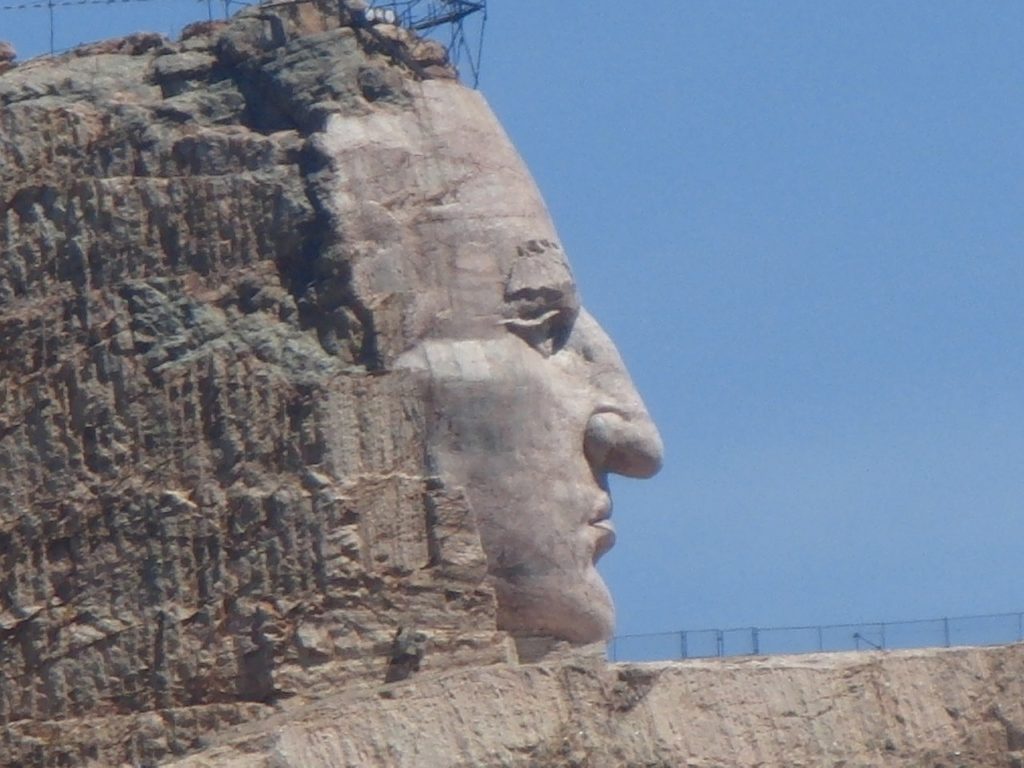

Last June, I drove from Seattle to Omaha with my son Eamon and my daughter-in-law Sakura. Our first day took us into western Montana. The second day saw us get to western South Dakota after a stop at the Little Big Horn. And the third day we started out with a quick blast through the Black Hills. We stopped in Deadwood, then headed to the Crazy Horse monument. That’s the picture above. If you pay a little extra when you visit the memorial, you can take a bus ride right up close to where the work on the monument is going on.

I had been to Crazy Horse once before, back in 1988, with my dad, when we were on our way to the Little Big Horn. Back then, you had to take the artists’ word that something would emerge from the mountain they were blasting away. At the visitors center, we paid a dollar for a chunk of granite from the rubble, faced with mica and shot through with what look like nodules of pyrite. The rock’s here on the dining room table as I write this. Twenty-three years later, something dramatic has been brought out of the mountain, and the scene around the area has changed, too. The site is now approached on a route that’s turned into a major highway, and the turnoff is controlled by the kind of traffic signal you see on expressways in San Jose. There’s an entrance plaza with maybe six lanes, just like going into a stadium parking lot. After that, there’s plenty of parking, a museum, shops, and beyond that, the mountain. Lots of people were visiting the early June day we stopped, though I wouldn’t say the place was overrun.

A few days ago, I came across Ian Frazier’s account of his visit to Crazy Horse, probably within a year or so of when we were there. Here’s what he saw, as recounted in his book “Great Plains“:

“In the Black Hills, near the town of Custer, South Dakota, sculptors are carving a statue of Crazy Horse from a six-hundred-foot-high mountain of granite. The rock, called Thunderhead Mountain, is near Mt. Rushmore. The man who began the statue was a Boston-born sculptor named Korczak Ziolkowski, and he became inspired to the work after receiving a letter from Henry Standing Bear, a Sioux chief, in 1939. Standing Bear asked Ziolkowski if he would be interested in carving a memorial to Crazy Horse as a way of honoring heroes of the Indian people. The idea so appealed to Ziolkowski that he decided to make the largest statue in the world: Crazy Horse, on horseback, with his left arm outstretched and pointing. From Crazy Horse’s shoulder to the tip of his index finger would be 263 feet. A forty-four-foot stone feather would rise above his head. Ziolkowski worked on the statue from 1947 until his death in 1982. As the project progressed, he added an Indian museum and a university and medical school for Indians to his plans for the grounds around the statue. Since his death, his wife and children have carried on the work.

“The Black Hills, sacred to generations of Sioux and Cheyenne, are now filled with T-shirt stores, reptile gardens, talking wood carvings, wax museums, gravity mystery areas (‘See and feel COSMOS–the only gravity mystery area that is family approved’), etc. Before I went there, I thought the Crazy Horse monument would be just another attraction. But it is wonderful. In all his years of blasting, bulldozing, and chipping, Ziolkowski removed over eight million tons of rock. You can just begin to tell. There is an outline of the planned sculpture on the mountain, and parts of the arm and the rider’s head are beginning to emerge. The rest of the figure still waits within Thunderhead Mountain–Ziolkowski’s descendants will doubtless be working away in the year 2150. This makes the statue in its present state an unusual attraction, one which draws a million visitors annually: it is a ruin, only in reverse. Instead of looking at it and imagining what it used to be, people stand at the observation deck and say, ‘Boy, that’s really going to be great someday.’ The gift shop is extensive and prosperous, buses with ‘Crazy Horse’ in the destination window bring tourists from nearby Rapid City; Indian chants play on speakers in the Indian museum; Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, local residents, and American Indians get in free. The Crazy Horse monument is the one place on the plains where I saw lots of Indians smiling.”

If you happen to go to the monument in the fall, there’s a walk to Korczak Ziokowski’s tomb every year on October 20, the anniversary of his death. Also interred there: his daughter Anne, who died last year just a few week’s before we visited. Her obituary, brief as it is, speaks volumes about the family’s commitment to the Black Hills.