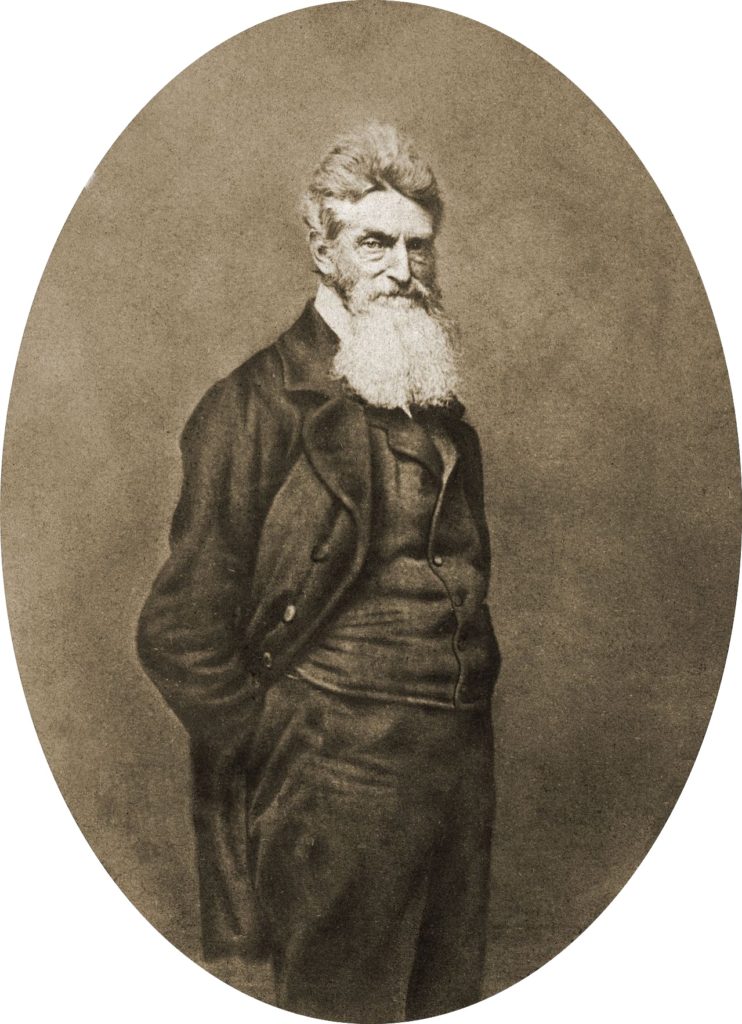

John Brown, the antislavery martyr notorious for terrorizing slavery sympathizers in Kansas and later for his failed attempt to ignite a war of slave liberation at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, is an uncomfortable figure. His means were violent, and from the very moment he came to national notice, in the 1850s, there has been a debate not just about those means but about whether he was a madman.

His capture, trial and execution gave Brown a platform to speak to an enthralled audience in both the North and South. For many in the slaveholding states, he served as living proof of Northerners’ ill intent toward their “way of life” and “peculiar institution.” In the “free states,” where abolitionists were a minority, he was at first denounced as a dangerous zealot or even insane.

Then the public, South and North, started absorbing his words, starting with a remarkable public interview with several elected officials, military officers (including Robert E. Lee) and newspaper reporters given as he lay wounded in the Harpers Ferry armory.

He answered questions about his motives: “I want you to understand that I respect the rights of the poorest and weakest of colored people, oppressed by the slave system, just as much as I do those of the most wealthy and powerful. This is the idea that have moved me, and that alone.”

And he ended with a warning: “I wish to say, furthermore, that you had better — all of you, people of the South — prepare yourselves for a settlement of this question. You may dispose of me very easily. I am nearly disposed of now; but this question is still to be settled — this negro question, I mean. The end of that is not yet.”

Brown was tried, sentenced and hanged all within six weeks of the Harpers Ferry incident. His behavior from the moment of his capture to his execution impressed his foes and his growing circle of supporters alike. The governor of Virginia, who was among those present at the armory during Brown’s interview, said the wounded man “inspired great trust in his integrity, as a man of truth.”

Brown’s brief address to the court at his sentencing cemented that reputation and became the vehicle for expanding the cause of abolition and making him the hero of that cause. , One passage:

“… Had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends — either father, mother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class — and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

The court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me further to “remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.” I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done — as I have always freely admitted I have done — in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments. — I submit; so let it be done!”

Of course, Brown was sentenced to hang. Before he was put to death, he made one last statement. in a note left for his jailer.

“I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had…vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”