One trip I try to make when I’m back in Chicago is to the cemeteries where my mom and dad and their families are buried.

My dad’s family cemetery, by which I mean the place where his parents and most of his mother’s family, the Sieversons, are interred, is Mount Olive, on Narragansett Avenue between Irving Park and Addison on the Northwest Side.

As kids, we were dragged out there for the occasional funeral. I only remember one in any detail: on a Saturday afternoon in September 1975 when Grandma Brekke was buried. I don’t recall that my father, whom I think was pretty stricken, stopped to take in the other family graves in the vicinity: His grandparents, Theodore and Maren Sieverson, for instance, or the several children surrounding them, or his Reque uncles and cousins, or the Helmuths or Simonsens or anyone else. Instead, we left the cemetery for a lunch at my grandmother’s church, Hauge Lutheran.

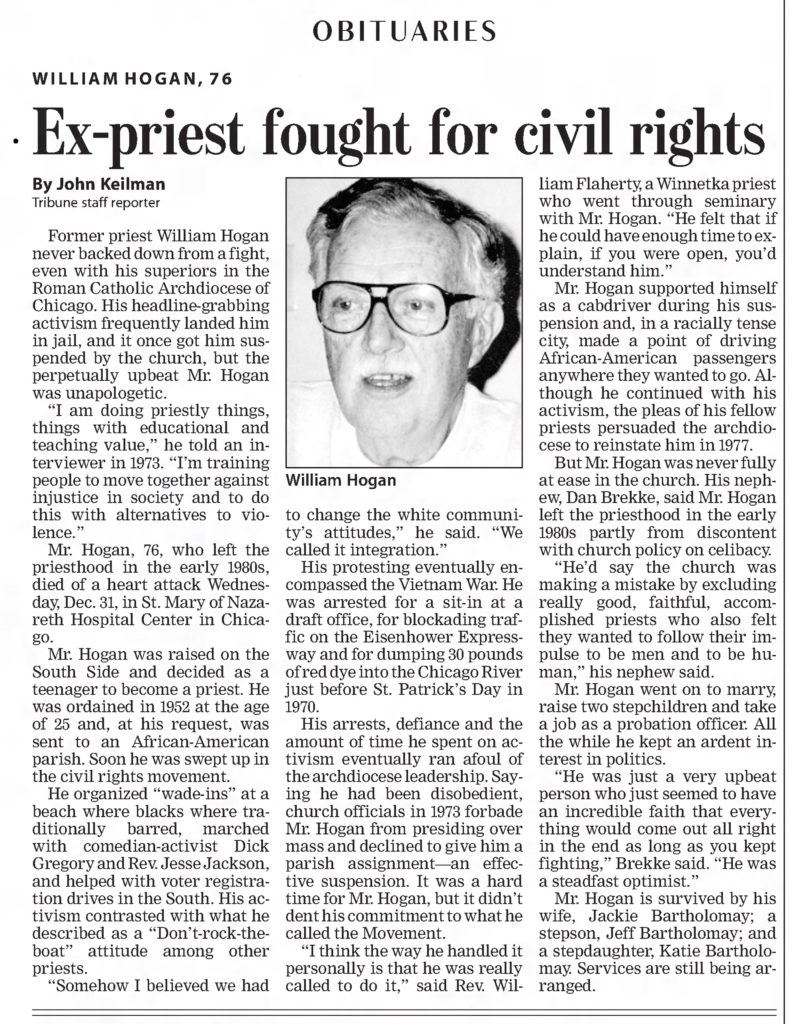

My siblings and I began visiting the cemeteries on our own — voluntarily — after our mom died in August 2003, followed by her last surviving sibling, our Uncle Bill, who died just four months later. My dad wanted to visit the cemeteries in the wake of those passings, for one thing, and we’d go with him. The two deaths so close together were so shocking in their suddenness that for me, I think going out to the cemetery when I was in town was a way to help process the grief. It also led us to find and visit all the family graves we had never seen before.

Anyway. I made my rounds last week, and yes, everyone was pretty much where I left them. Mount Olive was predominantly a Scandinavian cemetery until the last few decades, and it’s filled with graves of Norwegians and Swedes and probably some stray Danes whose families came to the city in the 19th century. The place hasn’t gone wild, but the years are catching up with those old Scandinavian sections, with lots of markers askew or tumbled down. There are a few that have markers stamped with the words “perpetual care.” My grandparents’ stone, which is rather unique in its simplicity, is still straight.

On this trip, I took a few pictures around the various grave sites, then drove toward the entrance, my next destination being my mom’s family cemetery on the far South Side. On the way out, though, I passed the inescapably phallic monument pictured at the top of the post. I must have passed it at least a dozen times in the past, but it had never registered. Maybe the light was just right this time.

The stone, which is 15 or 20 feet high, bears the name “O.A. Thorp.” Not a household name, at least where I live. Here’s what I can piece together:

Ole Anton Thorp was born in the town of Eidsberg, south of Oslo — then Christiania — in 1856. He emigrated to the United States and arrived in Chicago in 1880, where he started an import-export business.

The moment that made him a public figure arrived in 1892.

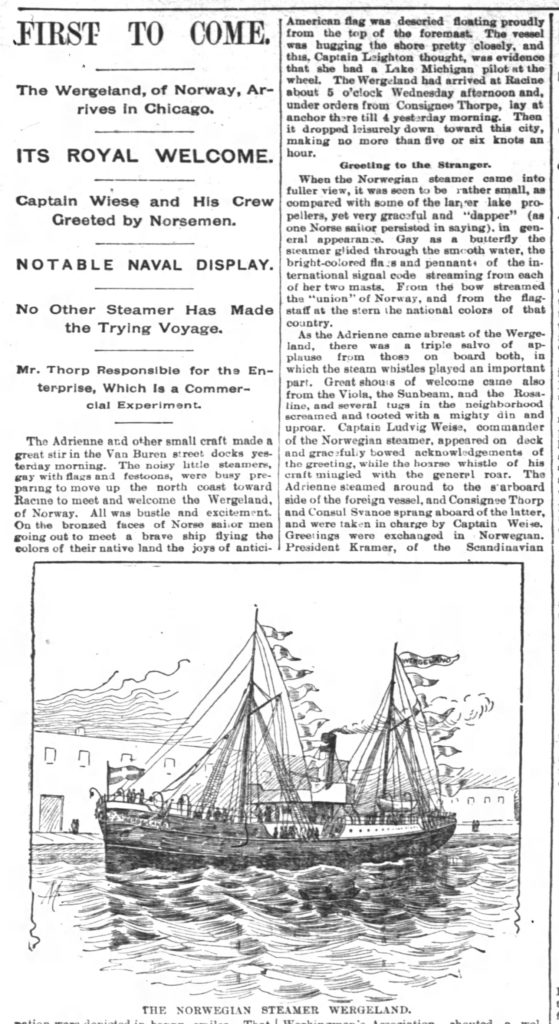

A promoter of all things Norwegian, including trade, Thorp had puzzled over a way to bring goods directly from Norway to Chicago, thus skipping the British and East Coast ports where they’d normally be handled at great expense. His solution was to charter a small freighter and bring his cargo up the St. Lawrence River and through the various canals connecting that waterway to the Great Lakes and Chicago.

The ship, the Wergeland, left Bergen with a cargo of salt herring and cod liver oil in early April. It made the crossing to the St. Lawrence without difficulty. But the canals of the era were so shallow that the steamer had to be unloaded before it passed through, then reloaded at the other end, a process that was repeated several times.

The Wergeland made it to Chicago on May 26, six weeks after leaving Norway, and was greeted as the first steam cargo vessel to make the voyage from Europe to the city.

So that was Thorp’s major claim to fame. A writeup on important Chicagoans done shortly afterward declared Thorp “has during the last decade done more for the development of trade between Norway and the United States than any other man in the West, and possibly more than anybody on this side of the ocean.”

He chartered steamers to make the journey again in 1893 and 1894, but then the venture seemed to fizzle. A magazine article a few years later — “Chicago Our Newest Seaport” in the May 1901 number of Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly — suggested that the nature of the cargo was part of the problem:

“… With each succeeding venture (Thorp) found it more and more difficult to dispose of a whole cargo of dried fish and cod liver oil at one time, especially in summer. In winter it might, perhaps, have been easier; but in winter navigation was closed, and it was impossible for his steamers to reach Chicago. Norway had little but fish and oil to send us … “

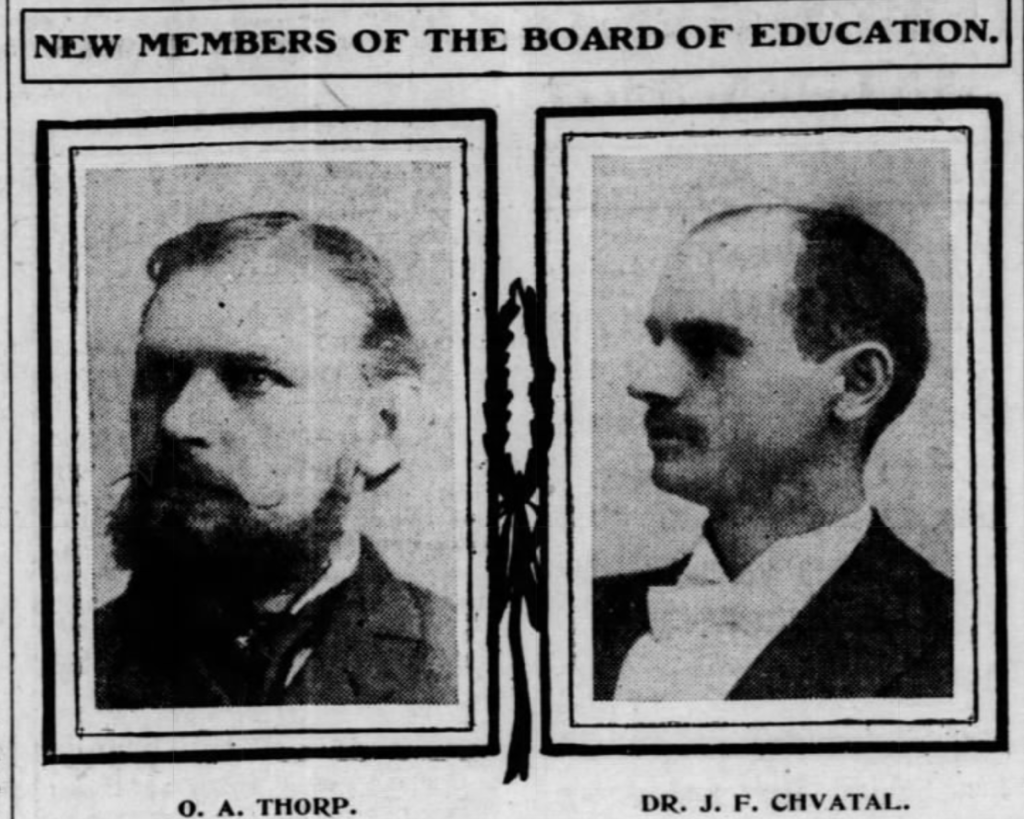

Thorp remained active in business, civic, and Norwegian American affairs in the city. He was one of the organizers of the campaign to commission a statue of Leif Erikson that was erected in Humboldt Park in 1901. He was appointed to the city’s school board in 1902; in the photo accompanying the appointment announcement in the Chicago Tribune, he looks vaguely like the accused Haymarket bombers of 1886.

How is Thorp remembered today? Hardly at all, though there’s a school named after him just a few blocks from Mount Olive Cemetery. And then there’s the giant O.A. Thorp shaft, rising amid the graves of less notable Norse folk.

In the individual graves around the monument, there are two markers with dates in January 1905.

One is for O.A. himself, who died Jan. 25, reportedly after surgery for an abdominal abscess. The other grave is for his daughter, Sara Olive Elizabeth, who died at age 14 on Jan. 5. The death notice in the Tribune says she passed at 4 in the afternoon at the family home in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood.