One afternoon not too long ago — sometime earlier this century, in any case — I found myself in Oakland, close to Piedmont Avenue, with nothing more on my to-do list for the day. I decided to take a walk up to Mountain View Cemetery. As always, in whatever cemetery I’m strolling through, I was captivated by the stories some grave markers suggest and took pictures of monuments that caught my eye.

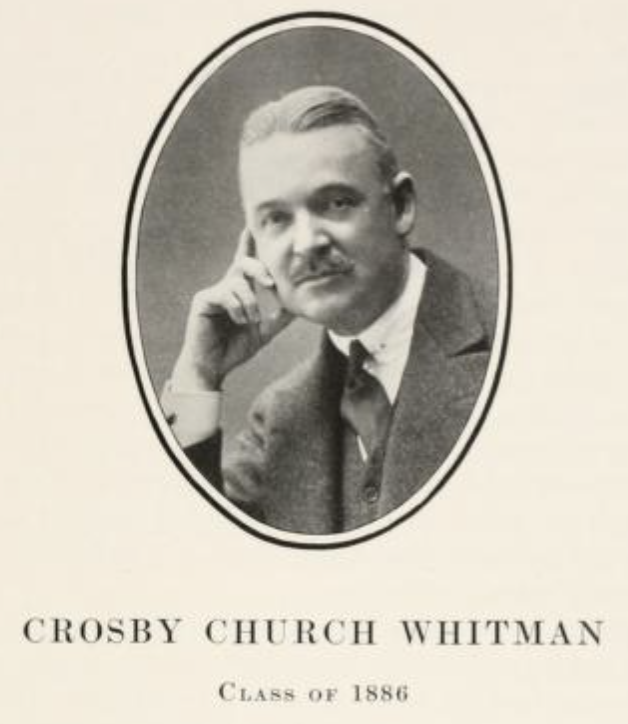

What grabbed me about the marker above? Well, the carefully rough-cut form, probably. The names, too: a family group — father, mother, and son, and the son’s imposing, formal name: Crosby Church Whitman. Also curious, to me: the detail related on the stone that the mother and son both died in Paris, with the younger Whitman dying in 1916, during World War I, but before the United States entered the war. What was the story there?

Much later, during hours when I should have been getting some outside air in my lungs, I looked up “Crosby Church Whitman” on our universal distributed reference library. One thing led to another, and soon the Whitmans were rubbing elbows with Gertrude Stein and Alice Babette Toklas.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. To start with the old Whitmans:

Bernard Crosby Whitman is the subject of a brief entry in the 1904 “National Cyclopedia of American Biography,” which says he was born in Massachusetts in 1827. He graduated from Harvard in 1846, studied law and was admitted to the bar in Maine in 1849. Then he heard about what was happening in California and came west, arriving in San Francisco in 1850. Among other activities of note, he was a Whig Party member of the state Assembly for one term and ran as a Know Nothing — nativist, exclusionary — candidate for Congress in 1856.

Mary Elizabeth Church was born in Albion, Michigan, in 1842. She was apparently brought to California as a child, and her hometown when she married Bernard was Rough and Ready, a Gold Rush settlement in Nevada County; newspaper accounts, in the Daily Alta California and Sacramento Union, reported the wedding ceremony took place in Nevada Clounty on July 14, 1858. (Take note of the dates and the ages they imply: If accurate, Bernard was 15 years Mary Elizabeth’s senior; she would have been 16 years old when she married a man twice her age. )

Their son, Crosby Church Whitman, was born in Benicia — in Solano County, northeast of San Francisco, and one of California’s early capitals — in 1864. He was sent east to prep school, graduated from Harvard in 1886 and then pursued a medical education in France and Germany. He practiced for a while at Johns Hopkins around the turn of the 20th century, then returned to France, where he resided and practiced medicine the rest of his life.

Bernard Whitman moved to Virginia City, Nevada, in 1864, the same year Crosby was born. The Comstock Lode was in full swing; Bernard is said to have taken “a prominent part in most of the litigation” related to the mines there. He was named to the Nevada Supreme Court and served a year as chief justice in the mid-1870s before moving to San Francisco, where he practiced law until his death from “an apoplectic stroke” in August 1885. His estate was reported to be worth about $10,000 — not a fortune, but enough for his survivors to get by on.

Presumably, Bernard was buried at Mountain View immediately after his death. But what about his wife and son, who according to the marker died in Paris much later?

Crosby Church Whitman turns up in newspaper accounts around 1910 as one of the founding physicians of the American Hospital in Neuilly, just outside Paris. When World War I broke out in 1914, he has asked to organize an “ambulance,” or field hospital, to help treat the masses of French and British soldiers wounded in the fight to stop the German advance on the capital.

Here’s how a 1920 volume, “Memoirs of the Harvard Dead in the War Against Germany,” described Dr. Whitman’s service, carried out under the auspices of the French Red Cross:

“With unfailing courtesy to all whom he met, and the many qualities which have endeared him to his friends, he devoted himself to his new duties, soothing sufferers in words as well as by professional skill, encouraging the despondent, and frequently providing at his personal expense the best apparatus for unfortunate amputated men when the time came for them to leave the ambulance. In the multiplicity of details, many annoyances were inevitable; but he always kept his cheerful serenity; it was said that a mere glance at his countenance was enough to make a wounded man feel sure that he was on the road to recovery.”

Crosby Whitman later organized a second field hospital. By the beginning of 1916, the Harvard account says, the sheer volume of work had overwhelmed him: “On the advice of his associates, he interrupted his work, as he supposed, for a few days; but his health failed rapidly. He passed away in his sleep, at his own residence in Paris, in the presence of his mother, the household, and the attending physicians. ” The consular record of his death, on March 28, 1916, lists the cause as “congestion of the brain.”

Mary Elizabeth Whitman had lived with her son at 20 Rue de Lübeck, in the 16th Arrondissement on the north bank of the Seine — about halfway between the Arc de Triomphe and Eiffel Tower — for years before his passing. And she stayed right there until her death in 1932, at age 90. Her death record lists the cause as “senility.”

How did the Whitmans make their way, after death, back to a cemetery in Oakland?

In Crosby Whitman’s case, the answer is that he didn’t. He was cremated and interred at the Suresnes American Cemetery, on the western outskirts of Paris.

And his mother? Well, it’s not quite clear to me. Yet. The record of her death shows she was cremated and her remains held, at least temporarily, at the American Cathedral in Paris. I’ve contacted people there to see whether there are any records of what happened after that.

So, that grave in Mountain View is the final resting place of one Whitman, and possibly two. The third member of the family remains in France.

What does any of that have to do with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas? Well, not a lot. But here’s something:

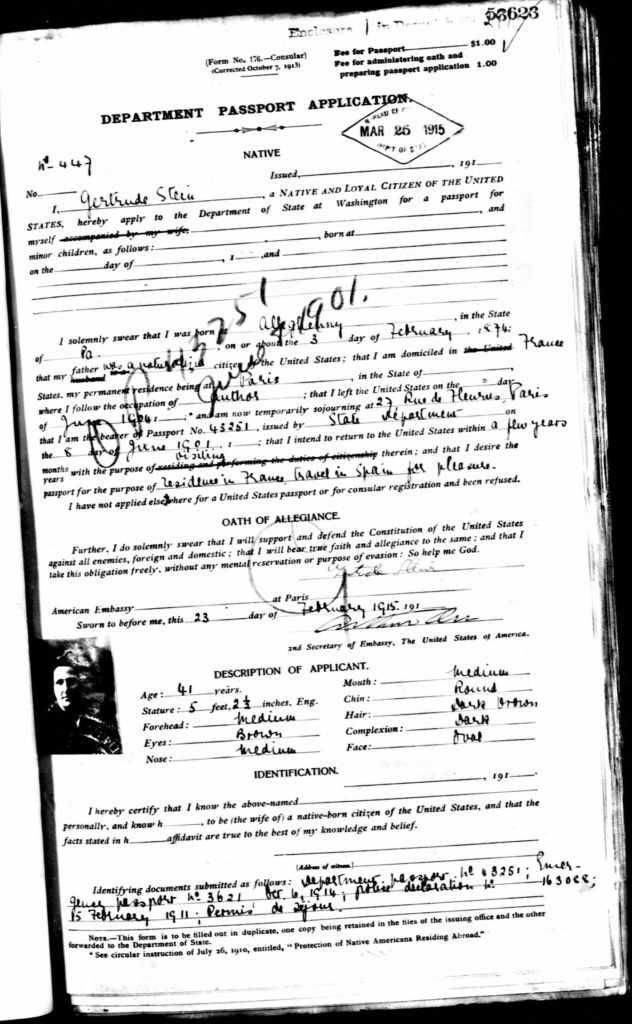

Looking for information on the Whitmans on Ancestry.com, among the resources I came across were passport applications made at the U.S. Embassy in Paris. The Whitmans applied for passports in December 1914. After Dr. Whitman explained his protracted absence from the United States, the passports were approved on March 25, 1915.

Crosby Whitman’s application is listed first in the passport file, followed by his mother’s. Turning to the very next page after Mary Elizabeth Whitman, I found this:

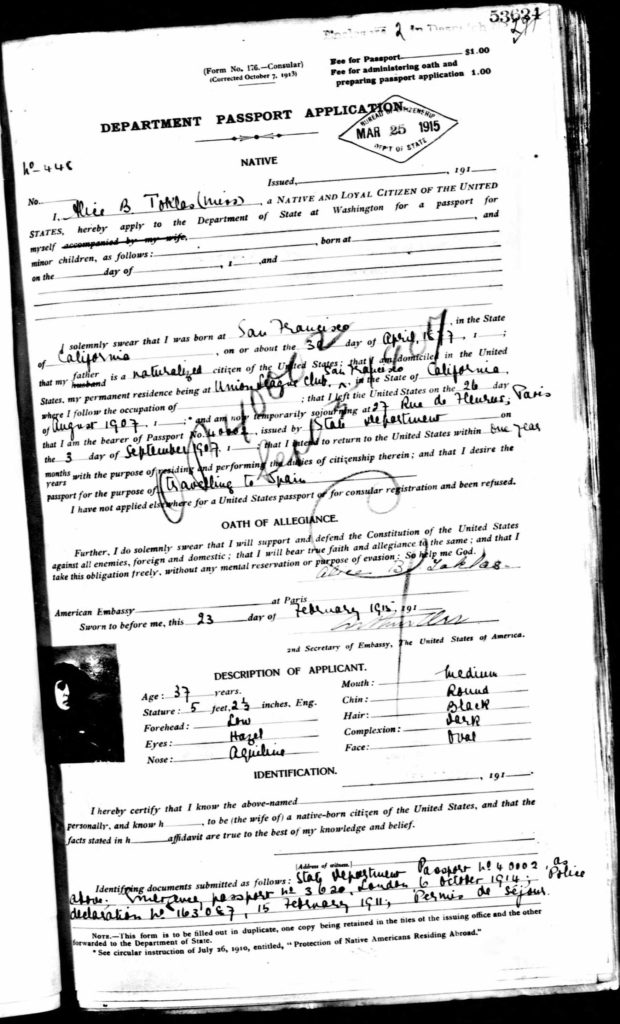

And on the very next page after that is this:

Of course, it’s just a coincidence . There’s nothing to suggest that, except for the accident of their simultaneous passport approvals, the Whitmans ever crossed paths with Stein and Toklas, who lived during these years about four kilometers away at 27 Rue de Fleurus, just outside the Luxembourg Gardens.

Long after the Whitmans passed away, and immediately after another World War, Gertrude Stein fell ill and was diagnosed with cancer. As she lay dying in the American Hospital, which Crosby Whitman had helped found decades earlier, Toklas kept watch by her bedside.

Toklas wrote later:

“I sat next next to her, and she said to me early in the afternoon, ‘What is the answer?’ I was silent. ‘In that case,’ she said, ‘what is the question?’ ”