Some pictures I’ve been sitting on for oh, the last year and a half. The September before last, Kate and The Dog and I took a Sunday field trip to the state fish hatchery just below Oroville Dam. It was a perfect day in the Sacramento Valley, clear and brilliantly sunny but not really hot — maybe 85 degrees. The first decent chinook salmon run in several years was under way, and in the three or four hours we hung around, several hundred people, almost all locals, showed up to take a look at the fish. A quick look at some of what we saw (captions to come):

Guest Observation: More on Crazy Horse

I just re-read Ian Frazier’s “Great Plains.” I had forgotten that among the many subjects he focuses on is Crazy Horse, the Lakota Oglala chief (how times change: a generation ago, his predominant identification among the wasichu would have been Sioux. I digress. Back to Frazier …). He’s got a chapter that ranges from a street in Manhattan, where he encounters a man who says he’s the grandson of Crazy Horse, to Fort Robinson, Nebraska, where Crazy Horse was killed. Here’s the end of the chapter, which I love for the way he reaches beyond a recitation of facts and tries to bring into the open the sentiment and emotion and meaning the facts inspire for him.

“Some, both Indian and non-Indian, regard him with a reverence that borders on the holy. Others do not get the point at all. George Hyde, who has written perhaps the best books about the western Sioux, says of the admirers of Crazy Horse, ‘They depict Crazy Horse as the kind of being never seen on earth: a genius in war, yet a lover of peace; a statesman, who apparently never thought of the interests of any human being outside his own camp; a dreamer, a mystic, and a kind of Sioux Christ, who was betrayed in the end by his own disciples–Little Big Man, Touch the Clouds … and the rest. One is inclined to ask, what is it all about?’

“Personally, I love Crazy Horse because even the most basic outline of his life shows how great he was; because he remained himself from the moment of his birth to the moment he died; because he knew exactly where he wanted to live, and never left; because he may have surrendered, but was was never defeated in battle; because, although he was killed, even the Army admitted he was never captured; because he was so free that he didn’t know what a jail looked like; because at the most desperate moment of his life he only cut Little Big Man on the hand; because, unlike many people all over the world, when he met white men he was not diminished by the encounter; because his dislike of the oncoming civilization was prophetic; because the idea of becoming a farmer apparently never crossed his mind; because he didn’t end up in the Dry Tortugas; because he never met the President; because he never rode on a train, slept in a boardinghouse, ate at a table; because he never wore a medal or a top hat or any other thing that white men gave him; because he made sure that his wife was safe before going to where he expected to die; because although Indian agents, among themselves, sometimes referred to Red Cloud as ‘Red’ and Spotted Tail as ‘Spot,’ they never used a diminutive for him; because, deprived of freedom, power, occupation, culture, trapped in a situation where bravery was invisible, he was still brave; because he fought in self-defense, and took no one with him when he died; because, like the rings of Saturn, the carbon atom, and the underwater reef, he belonged to a category of phenomena which our technology had not then advanced far enough to photograph; because no photograph or painting or even sketch of him exists; because he is not the Indian on the nickel, the tobacco pouch, or the apple crate. Crazy Horse was a slim man of medium height with brown hair hanging below his waist and a scar above his lip. Now, in the mind of each person who imagines him, he looks different.

“I believe that when Crazy Horse was killed, something more than a man’s life was snuffed out. Once, America’s size in the imagination was limitless. After Europeans settled and changed it, working from the coasts inland, its size in the imagination shrank. Like the center of a dying fire, the Great Plains held that original vision longest. Just as people finally came to the Great Plains and changed them, so they came to where Crazy Horse lived and killed him. Crazy Horse had the misfortune to live in a place which existed both in reality and in the dreams of people far away; he managed to leave both the real and the imaginary place unbetrayed. What I return to most often when I think of Crazy Horse is the fact that in the adjutant’s office he refused to lie on the cot. Mortally wounded, frothing at the mouth, grinding his teeth in pain, he chose the floor instead. What a distance there is between that cot and the floor! On the cot, he would have been, in some sense, ‘ours’: an object of pity, an accident victim, ‘the noble red man, the last of his race, etc. etc.’ But on the floor Crazy Horse was Crazy Horse still. On the floor, he began to hurt as the morphine wore off. On the floor, he remembered Agent Lee, summoned him, forgave him. On the floor, unable to rise, he was guarded by soldiers even then. On the floor, he said goodbye to his father and Touch the Clouds, the last of the thousands that once followed him. And on the floor, still as far from white men as the limitless continent they once dreamed of, he died. Touch the Clouds pulled the blanket over his face: ‘That is the lodge of Crazy Horse.’ Lying where he chose, Crazy Horse showed the rest of us where we are standing. With his body, he demonstrated that the floor of an Army office was part of the land, and that the land was still his.”

Berkeley Earthquake Report

Woke up to some shaking at 5:33 a.m. The technical details are here at the U.S. Geological Survey website: Magnitude 4.0.

The experience: I was lying in bed awake. First, a distant rumble, then a good sharp jolt. A pause of a couple of seconds, and then another stronger jolt, followed by five to ten seconds of light shaking.

It’s always the seconds after the first shaking sensation that I kind of dread. How bad is this thing going to be? Is it going to intensify, or is that it?

Here’s the Google map of the epicenter locaction, about two, two and a half miles north of us:

View Larger Map

And with that, I’m going to follow a colleague’s advice and go back to bed.

A New Mini-Project: ‘Posted in Berkeley’

Pretty soon after I came to Berkeley in the mid-70s, I noticed that people here like to communicate via wall and telephone pole. Usually, they’ve lost something and are hoping a poster will help their lost dog, cat, earring, belt buckle, notebook, or laptop computer come home.

Why do they catch my eye? Sometimes they’re a kind of found poetry. Sometimes there’s some news there. Sometimes the postings are poignant or tell a story. Sometimes they’re funny, and sometimes unintentionally so. Sometimes there’s a bit of unhinged emotion or alarm on display (see above).

Anyway, after occasionally shooting these things for the past few years, I’m collecting them in one place, a Tumblr I’ve set up called Posted in Berkeley. I’ve put up about a dozen postings from the past year or two. It’s set up to allow others to submit posts, too. (Non-Berkeley-ites, feel free to submit. Maybe I’ll come up with a name that’s more inclusive/expansive than “Posted in Berkeley.” My first thought, “Post No Bills,” is already taken.)

Superior Suds

Moonlight, Self-Portrait

The International Space Station was advertised to make a two-minute pass to the southwest and south tonight. When it showed up, it was actually visible for close to five minutes. I tried to take time exposures of it tracking across the sky, but those didn’t pan out. There was enough moonlight, though, to play with a long exposure of my shadow on the sidewalk.

A Month-Plus of Oakland Violence

On Super Bowl Sunday, there was a shooting in the 3300 block of Adeline Street in West Oakland. What made it stand out from the background of shootings in the city was the toll: seven reported wounded. So that afternoon, I put together a map and list of the reported shootings over the past week. That spate of violence was enough for Oakland Police Chief Howard Jordan to call a press conference, promise to redouble the department’s efforts to fight crime, and to appeal to the public to report shootings and illegal guns to police.

There’s little evidence that the pace of the shootings has slackened since then. The toll for the past month, going back to January 29, is 14 dead and 29 wounded (one of the killings was a stabbing; one of those wounded was a man shot by police after a reported robbery).

But that toll minimizes the frequency of firearms incidents in the city. From Feb. 1 through today, the Oakland police report 45 incidents of “assault with a firearms on a person,” 41 incidents of shooting at dwellings or vehicles (either inhabited or uninhabited), 94 robberies involving firearms, seven cases of willfully discharging a firearm in a negligent manner, 14 cases of exhibiting firearms during the commission of another crime, two cases of carjacking with a gun (there are a few incidents in the OPD database listed under more than one of these categories).

An updated map is below. Each placemarker includes the available details on the incidents reported (I’ve limited the maps to homicides, reported shootings of people, and other incidents in which guns were apparently fired).

One pattern in the map: It’s striking to see how few shootings occur above (east or north of) Interstate 580. If there’s a geographic boundary to shootings that seems to hold for most of the city, that’s it.

View A Month of Oakland Violence in a larger map

‘A Ruin, Only in Reverse’

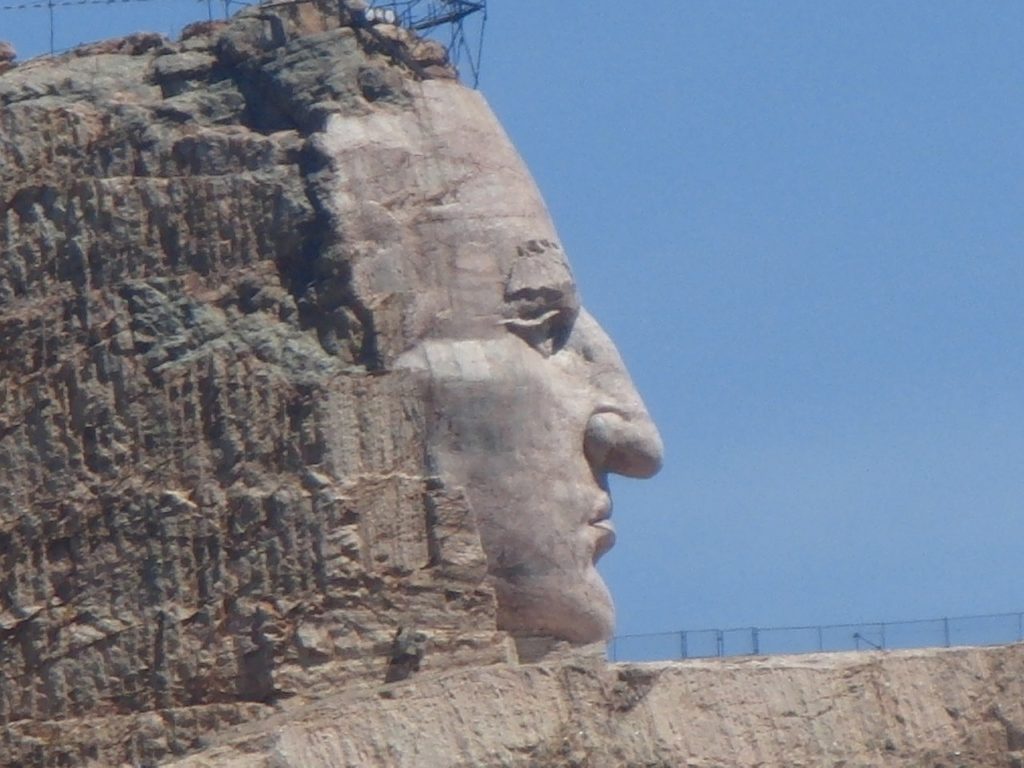

Last June, I drove from Seattle to Omaha with my son Eamon and my daughter-in-law Sakura. Our first day took us into western Montana. The second day saw us get to western South Dakota after a stop at the Little Big Horn. And the third day we started out with a quick blast through the Black Hills. We stopped in Deadwood, then headed to the Crazy Horse monument. That’s the picture above. If you pay a little extra when you visit the memorial, you can take a bus ride right up close to where the work on the monument is going on.

I had been to Crazy Horse once before, back in 1988, with my dad, when we were on our way to the Little Big Horn. Back then, you had to take the artists’ word that something would emerge from the mountain they were blasting away. At the visitors center, we paid a dollar for a chunk of granite from the rubble, faced with mica and shot through with what look like nodules of pyrite. The rock’s here on the dining room table as I write this. Twenty-three years later, something dramatic has been brought out of the mountain, and the scene around the area has changed, too. The site is now approached on a route that’s turned into a major highway, and the turnoff is controlled by the kind of traffic signal you see on expressways in San Jose. There’s an entrance plaza with maybe six lanes, just like going into a stadium parking lot. After that, there’s plenty of parking, a museum, shops, and beyond that, the mountain. Lots of people were visiting the early June day we stopped, though I wouldn’t say the place was overrun.

A few days ago, I came across Ian Frazier’s account of his visit to Crazy Horse, probably within a year or so of when we were there. Here’s what he saw, as recounted in his book “Great Plains“:

“In the Black Hills, near the town of Custer, South Dakota, sculptors are carving a statue of Crazy Horse from a six-hundred-foot-high mountain of granite. The rock, called Thunderhead Mountain, is near Mt. Rushmore. The man who began the statue was a Boston-born sculptor named Korczak Ziolkowski, and he became inspired to the work after receiving a letter from Henry Standing Bear, a Sioux chief, in 1939. Standing Bear asked Ziolkowski if he would be interested in carving a memorial to Crazy Horse as a way of honoring heroes of the Indian people. The idea so appealed to Ziolkowski that he decided to make the largest statue in the world: Crazy Horse, on horseback, with his left arm outstretched and pointing. From Crazy Horse’s shoulder to the tip of his index finger would be 263 feet. A forty-four-foot stone feather would rise above his head. Ziolkowski worked on the statue from 1947 until his death in 1982. As the project progressed, he added an Indian museum and a university and medical school for Indians to his plans for the grounds around the statue. Since his death, his wife and children have carried on the work.

“The Black Hills, sacred to generations of Sioux and Cheyenne, are now filled with T-shirt stores, reptile gardens, talking wood carvings, wax museums, gravity mystery areas (‘See and feel COSMOS–the only gravity mystery area that is family approved’), etc. Before I went there, I thought the Crazy Horse monument would be just another attraction. But it is wonderful. In all his years of blasting, bulldozing, and chipping, Ziolkowski removed over eight million tons of rock. You can just begin to tell. There is an outline of the planned sculpture on the mountain, and parts of the arm and the rider’s head are beginning to emerge. The rest of the figure still waits within Thunderhead Mountain–Ziolkowski’s descendants will doubtless be working away in the year 2150. This makes the statue in its present state an unusual attraction, one which draws a million visitors annually: it is a ruin, only in reverse. Instead of looking at it and imagining what it used to be, people stand at the observation deck and say, ‘Boy, that’s really going to be great someday.’ The gift shop is extensive and prosperous, buses with ‘Crazy Horse’ in the destination window bring tourists from nearby Rapid City; Indian chants play on speakers in the Indian museum; Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, local residents, and American Indians get in free. The Crazy Horse monument is the one place on the plains where I saw lots of Indians smiling.”

If you happen to go to the monument in the fall, there’s a walk to Korczak Ziokowski’s tomb every year on October 20, the anniversary of his death. Also interred there: his daughter Anne, who died last year just a few week’s before we visited. Her obituary, brief as it is, speaks volumes about the family’s commitment to the Black Hills.

Berkeley: The Neighborhood Files

When you tell Bay Area acquaintances that you live in Berkeley, usually they’ll ask, “Where?” I sometimes feel it’s a way of trying to get an idea of where you’re standing on the socioeconomic ladder. If you say “the Hills,” that conjures pictures of secluded streets, sweeping views, and steep home prices. If you say “West Berkeley” or “South Berkeley,” that may convey a picture of a flatlands neighborhood that’s less white than the rest of the city, maybe more affected by street crime, maybe a place you can find what passes in these parts for affordable housing. “Elmwood” to me says genteel, tree-lined streets studded with big, beautiful old houses.

Our area is North Berkeley, a comfortable part of the city, if not a rich one. An area known for its proximity to the Gourmet Ghetto, a good-food neighborhood that’s actually been institutionalized. We’ve got one of the best produce markets in the country here, and every block sports at least one Prius or electric car at the curb. We’ve got decent schools and parks nearby. We’re close to public transportation, and this is one of the places where the unique and wonderful casual carpool started.

But those generalities don’t do much to show you the particulars of life in the neighborhood. You don’t pick up on the block parties, the parents cajoling kids to get into, or out of, the car, the neighborhood feuds, the badly parked cars, the influx and outflow of commuters every day, the hired gardeners and dog walkers, the clipboard-toting solicitors for political and social causes, the dogs barking at the postal carriers, the local dogs and cats and their tendencies, the FedEx and the UPS drivers, the new neighbors up the block, the discarded TVs or settees on the curb with signs that say “free,” or the lost cat posters and announcements for yoga classes on the telephone poles.

You also don’t encounter the occasional house that seems, apart from neighboring structures, to be sinking into ruin. Maybe we notice that more now that The Dog has us on regular rounds on nearby streets, but there’s one block in particular that stands out for having a couple of spectacular wrecks. One of the buildings appears to be a duplex–there are side-by-side entrances. A couple of the window panes have been replaced by plywood. There’s no sign of anyone going in and out, and the curtains appear to be permanently drawn. Right next door is a sprawling two-story house that also looks like it’s in a losing battle with weather and gravity. There’s a collection of junk and old boxes on the porch and a big liquidambar tree in the front yard; right now, weedy spring growth is emerging from an autumnal carpet of dead leaves. I’ve seen someone at this place–a woman who on occasion suns herself on a green plastic chair in a clear patch of driveway. She barked at me once two or three years ago for walking the dog off-leash. Occasionally, there’s a battered early-’70s Chevy Impala parked on the curb. Evidently it’s a live-in vehicle, and you’lI see it cruising the area (top speed about 20 mph).

The overall effect: a sort of Berkeley-ized version of Miss Havisham’s place in “Great Expectations.” You wonder whether there’s someone just barely hanging on to these places.

Not all is ruin, though. Outside that first house, a couple of shrubs are flowering right now (the pictures up above). The one on the left is a kind of magnola. The one on the right I’m not sure about. Below is the second house mentioned above.

Left Only, Right Only

Wednesday evening, Milvia Street and Yolo Aveneu, as the sun set on an unbelievable February day: clear, temperature in the low 70s, the streets abloom (yes, after seeing winter afternoons like this for 35 years, I think they’re unbelievable–I guess I still have that much Chicago in me). Creeping into the quiet spaces of that reverie, the thought that the weather is eating away at the little bit of a snowpack that’s built up in the mountains. From here, the year ahead looks very dry.