A week before Christmas, while I was visiting family in Chicago and environs, I drove out to the south suburbs to see two old friends, Jane and Mort. They were teachers at my high school, Crete-Monee. Mort taught English and writing, and we formed a lasting bond over that. I became friends with Jane when she married Mort. We’ve stayed in close enough touch that I still try to drop in once in a while, and I’ve never forgotten their phone number. For the afternoon and evening I was at their house in Crete last month, we talked up a storm, lit the last of the Hanukkah candles, and ate pizza. By the time I left to drive back to the North Side, a weak, intermittent snow was falling. I gassed up in University Park, which I still think of as Park Forest South or even Wood Hill, then drove west on Exchange and north on Monee Road toward our old house.

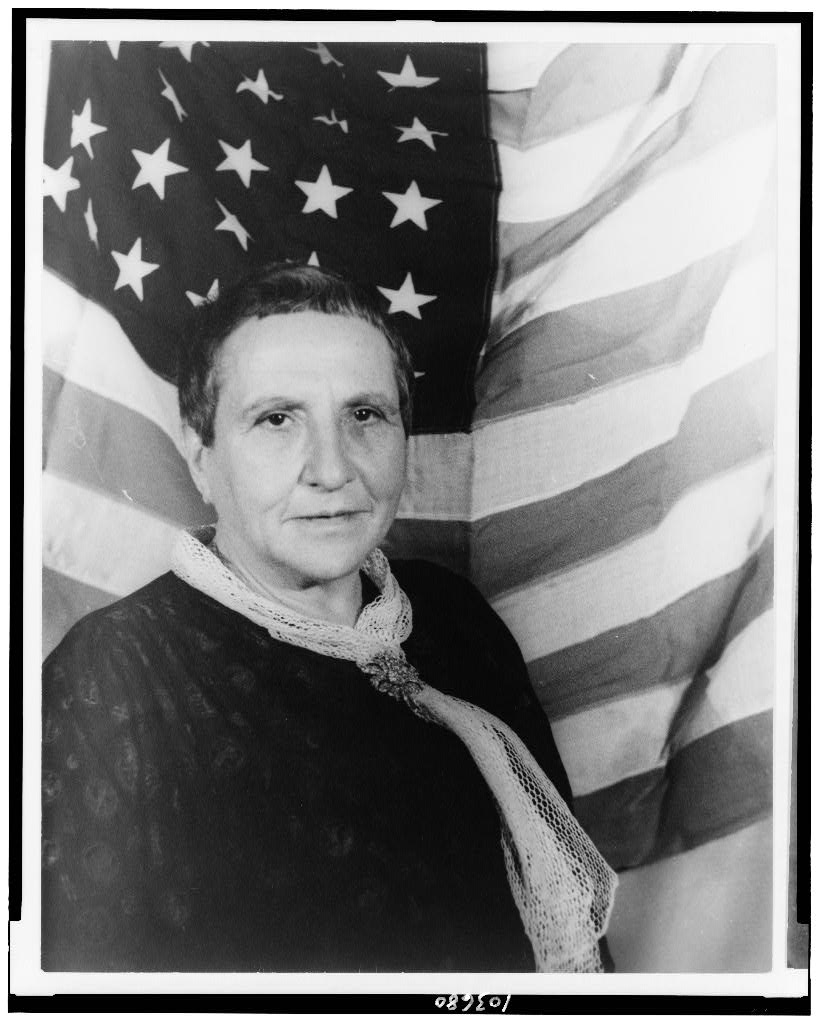

I parked first down near the bridge over Thorn Creek, at the intersection with Monee and Stuenkel roads. That’s the picture above. I remember that corner during a heavy pre-Christmas snowstorm one night when I was 16 or so. I think school had let out for the holiday earlier that day, and then it started to snow. One of our friends from the road was coming back from college in Iowa. We roamed the neighborhood–it consisted of a couple short stretches of rural roads–and marveled at how heavy the snow was and how quickly it was piling up. We wound up beneath the lamp on the corner, talking, watching the snow come down through the light, talking some more. Maybe there was some snowball mischief involved.

After I took the picture, I got in the car and started to drive toward Park Forest. But I thought, no, I wanted to go up our old road and see if there was anything to be seen up there.

Oak Hill Drive was a quarter-mile long lane, arrow straight through stands of oak and maple and up a little rise, barely wide enough for two cars. It was gravel when we moved onto the road in 1966, and there was always a swampy, potholed stretch about a third of the way up that seemed immune to all efforts to fix it. Walking up there in the dark, it seemed almost inevitable you’d stumble into one of the muddy ruts. The road was eventually tarred and chipped, then paved at some point.

I drove up to the end, where the road ends in a cul de sac and where our old driveway follows a fence line into the trees. I parked in the turn-around–aware the whole time of what we had always thought when we saw a car come to a stop out there and douse its lights: “Someone’s up to no good.” But I parked anyway, got out of the car, and walked back down the road.

It was then I had a strange sense of not quite belonging, of being in a place I knew intimately and not at all.

About 20 of the two dozen homes along the road, each built on a lot of about an acre, were there when I grew up. I remember each house, who lived there, and whether we were on good terms. The Sullivans. The Flemings. The Euchners. The Phillipses. The Pattersons. The Janowiaks. The O’Donnells, Everharts, Ihles, Keetons, and Hartmanns. A parent committed suicide in one house. Another was home to a family that lost both a mother and a brother to untimely deaths. And without looking too hard, one might find equally dark and disturbing stories up and down the road.

Looking across one section of open yards, I saw a light in the back room of a house I knew well–the home of my best friend growing up out there. That lamp looked like it might have been the same one that was shining there on my last visit, about 30 years ago. It might be. My friend’s parents are still there. But all of those other people I remember are long since gone.

I got down to the bottom of the road, then turned around and started back up. A car turned into the road and passed me. I wondered what the driver was thinking. Probably some variation on, “What’s somebody doing out here in the snow this late at night?” I realized my imagined answer to such a question–“I grew up out here”–wouldn’t explain much. What most people would see was a middle-aged guy walking in a dark, cold place the week before Christmas.

I watched the car turn into a driveway, then listened to the loud crunch of gravel under the tires. It occurred to me the driver might not have seen me at all. Maybe I’d been invisible. A ghost visiting his memories.

Like this:

Like Loading...