I read a piece in The New York Times in the last couple of weeks that suggested a common sense way of doing — what would you call it? — historical lexicography, maybe. Or in plain English: investigating when certain words and terms came into common use.

Here’s the technique: Go to Google Books, then search on your term. Sift through the pile of results until you get a rough sense of the earliest references. It gives an approximation of when terms appeared — sort of a quick and easy way of what the Oxford English Dictionary’s researchers and informants have been doing for more than a century in tracking down words to their original uses and contexts.

As I said, you’ll have to sift through a lot of results to get an idea of when your word or phrase appeared, though Google helps with an advanced search that lets you look for publications by date. For me, anyway, the sifting is part of the fun.

I’m curious about when the idea of “ethics in journalism” or “journalism ethics” gained currency. I’m not surprised to find lots written about it, including works that deal with the invention of journalism ethics, published in the last ten, twenty, thirty years. Searching for stuff written before 1970, I find a 1922 essay in the International Journal of Ethics, “Journalism, Ethics, and Common Sense.” It starts:

“Several books and many articles have been published lately on the far from fresh subject of journalistic ethics–rather the lack of ethical standards and principles in contemporary journalism. Some writers have not hesitated to indict the entire newspaper business or profession on such charges as deliberate suppression of certain kinds of news, distortion of news actually published, studied unfairness toward certain classes, political organizations, and social movements, systematic catering to powerful groups of advertisers, brazen and vicious faking and reckless disregard of decency, proportion, and taste for the sake of increased profits. Other writers have been more moderate and have recognized that there are three species of newspapers–good, intelligent, honest newspapers, morally pernicious and intellectually contemptible newspapers, and colorless, indifferent, innocuous newspapers.”

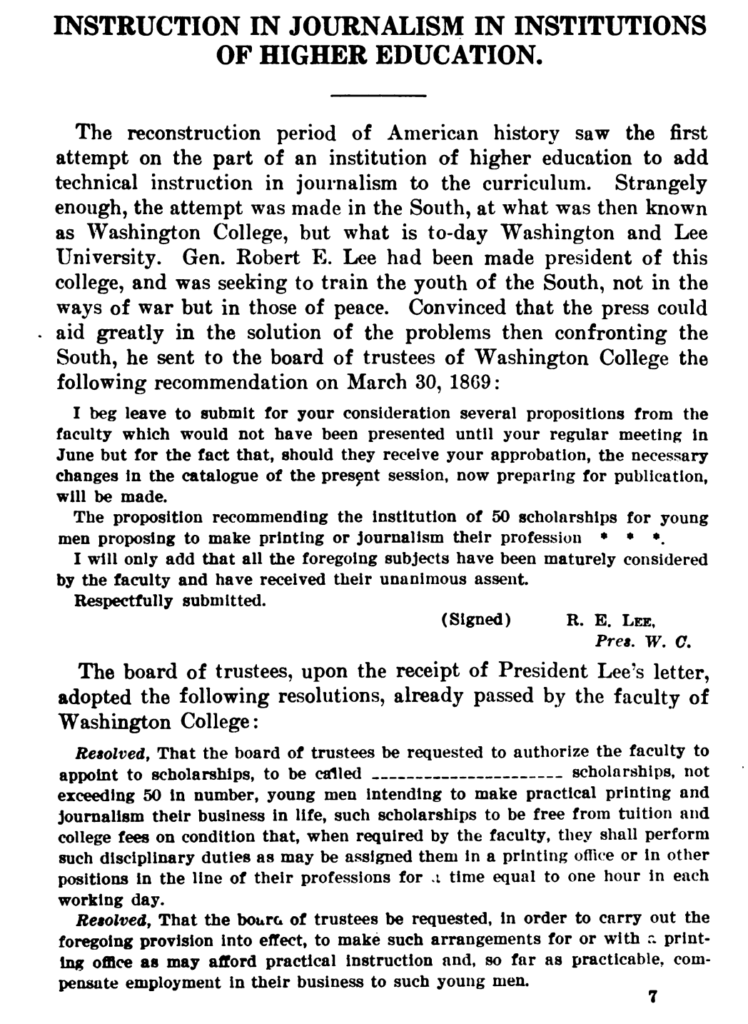

I want to go further back. Here’s an entry for a 1918 publication, “Instruction in Journalism in Institutions of Higher Education,” from the Department of the Interior’s Office of Education. I’m amazed who I find there.

(Washington and Lee’s Department of Journalism says this about the program’s inception: “To help rebuild a shattered South, the college developed several new programs; among them were agricultural chemistry, business and journalism. It is not clear how many young men, if any, actually received the scholarships that Washington College widely advertised, but it is certain that the program lasted only a few years.” A permanent school was established in the 1920s.)

The Office of Education’s account includes the warm welcome Lee’s idea was accorded by the doyens of the profession. “Frederic Hudson, the managing director of the New York Herald, when asked, ‘Have you heard of the proposed training school for journalists?’ promptly replied, ‘Only casually in connection with Gen. Lee’s college and I can not see how it could be made very serviceable. Who are to be the teachers? The only place where one can learn to be a journalist is in a great newspaper office. ”

That reaction puts me in mind of what I still hear from long-time journalists; except now they’re all for journalism education, and they’re decrying all this online stuff that’s breaking down their walls and their bottom lines.

(And as to the original question: the earliest instance I can find of “journalism ethics” — actually “ethics of journalism” — is 1846.)