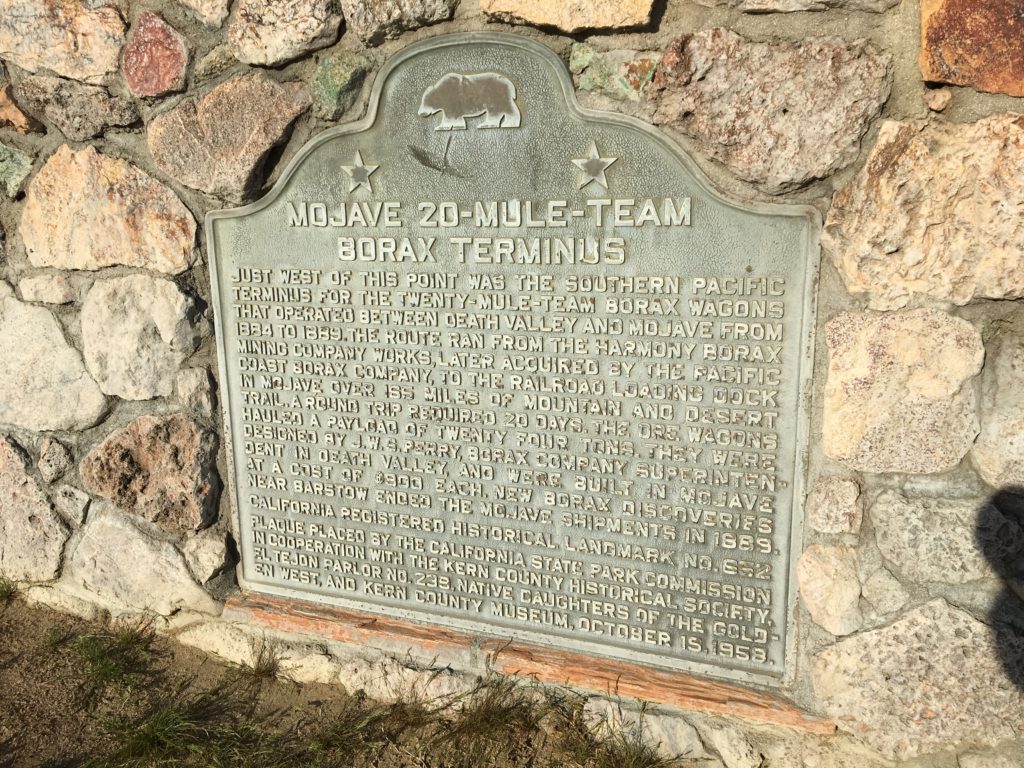

Kate and I encountered the marker above a few years back while driving on a back road in the southern Sierra Nevada foothills. The text is hard to read, but it’s transcribed in full below.

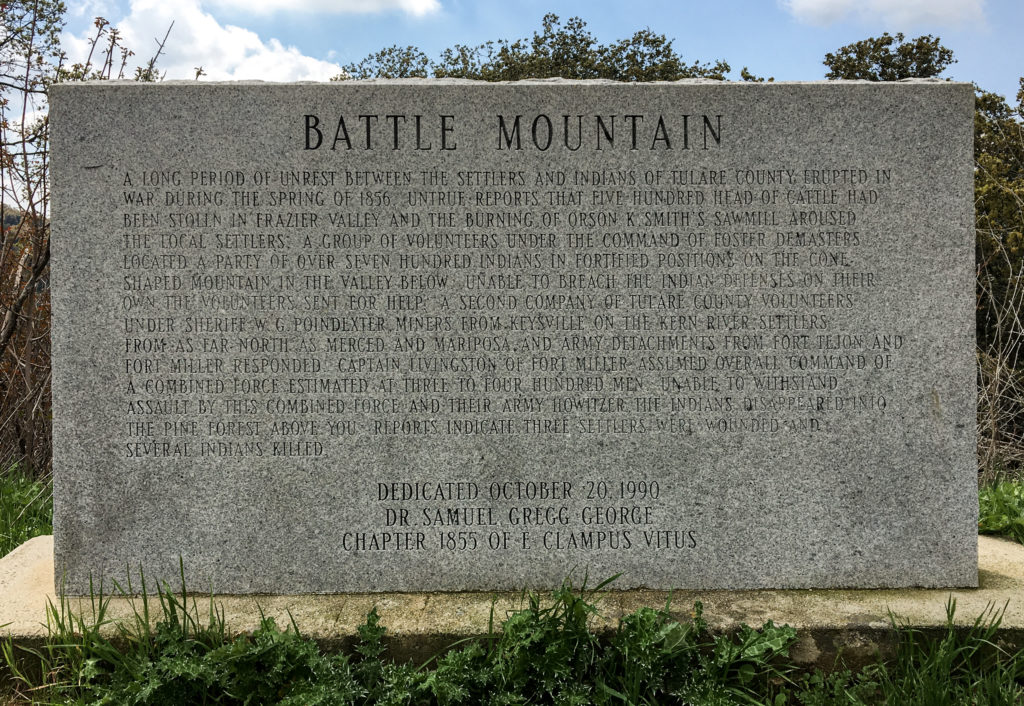

Battle Mountain A long period of unrest between the settlers and Indians of Tulare County erupted in war during the spring of 1856. Untrue reports that five hundred head of cattle had been stolen in Frazier Valley and the burning of Orson K. Smith's sawmill aroused the local settlers. A group of volunteers under the command of Foster DeMasters located a party of over seven hundred Indians in fortified positions on the cone-shaped mountain in the valley below. Unable to breach the Indian defenses on their own, the volunteers sent for help. A second company of Tulare County volunteers under Sheriff W.G. Poindexter, miners from Keysville on the Kern River, settlers from as far north as Merced and Mariposa, and Army detachments from Fort Tejon and Fort Miller responded. Captain Livingston of Fort Miller assumed overall command of a combined force estimated at three to four hundred men. Unable to withstand assault by this combined force and their Army howitzer, the Indians disappeared into the pine forest above you. Reports indicated three settlers were wounded and several Indians killed. Dedicated October 20, 1990 Dr. Samuel Gregg George Chapter 1855 of E Clampus Vitus

When it comes to roadside markers, the easiest thing in the world to do is pick apart their abbreviated rendition of past events. There is no way that even a relatively prolix text, such as the one on this marker, can convey much in the way of detail or nuance. Too bad they don’t contain hyperlinks, though now that I’ve had that thought: QR codes. You know: “To read more about the Chicago Fire, or the Haymarket Square affair, or the assassination of Mayor Carter Harrison, scan this code.” (Yes, I know there is history outside my native city.)

So perhaps the highest and best functions of these markers is to awaken someone’s interest to past events and send them looking for more. I know that’s what happened five years ago when I was driving around Oroville, a town that had been evacuated because of fears that part of a dam would give way, and happened across a marker commemorating Ishi.

As I wrote at the time, “Ishi is an instantly recognizable name for those who have spent any time in California. Ishi is the legendary last member of his native tribe, the Yahi. In 1911, he was ‘discovered.’ Meaning: starved and alone, he gave up his home country in the foothills on the northeastern side of the Sacramento Valley and entered “civilized” California.”

Here’s what Ishi’s plaque says:

The Last Yahi Indian For thousands of years, the Yahi Indians roamed the foothills between Mt. Lassen and the Sacramento Valley. Settlement of this region by the white man brought death to the Yahi by gun, by disease, and by hunger. By the turn of the century only a few remained. Ishi, the last known survivor of these people, was discovered at this site in 1911. His death in 1916 brought an end to Stone Age California.

“His death brought an end to Stone Age California.” An entire people, an entire world, dispatched in one succinct sentence. But stumbling upon the plaque prompted me to finally read a well-known and unwittingly tragic account of Ishi’s life and final years, “Ishi in Two Worlds.” It’s a story I think of often as a reminder of how complex the history around us is and how little I know.

But back to Battle Mountain. What to make of this marker, erected in 1990 by a society dedicated to the lore, if not always the true history, of old California? There are some details in the account that don’t smell right. One I wondered about was the notion that a force of white volunteers encountered “over seven hundred Indians in fortified positions.” The concluding line about casualties — three white settlers wounded “and several Indians killed” also sounds vague and sanitized.

What do other sources say?

Wild West magazine recounts the battle as part of “The Tule River War.” That account suggests a much higher casualty count among the Native Americans — members of the Yokuts group of tribes who also faced some ugly post-battle repercussions.

Searching the excellent California Digital Newspaper Collection, here’s contemporary comment from the May 31, 1856, edition of the Sacramento Union:

The Last “End of the Tulare War.’— We have frequently had occasion to remark that the accounts of Indian hostilities, not only in the north, but in the south, are almost invariably exaggerated. A small affair is soon magnified into a battle, and the origin is not unfrequently attributed to Indian outrages, when the account should read “white man’s oppression.” The following extract from a private letter written to a gentleman in San Francisco, from a friend at Fort Miller, and bearing date the 25th of May, is the latest, and it may be one of the most truthful accounts from that quarter:

“The Indian war is defunct. The volunteers from this place have returned, swearing most roundly at the [white] Four Creeks people, whom they term Petticoat Rangers, from a kind of armor made with canvas padded with cotton, which they wear in shape of a frock or blouse around their persons for protection. The whole matter has been a cowardly farce, the threatening legions of Indians turning out to be but about one hundred, seeking refuge in a brush from the rowdies, who, on the least occasion, delight in the sport of shooting them.

“As in all cases of the kind, the fault has been with the whites. The herds of cattle said to have been stampeded, have turned out to be a single calf taken to supply the deficiency of meat during an Indian feast. Retaliation, of a brutal character, for this trifling offense, created all the disturbance.”

There are plenty of other newspaper accounts of the “war” published around the same time. Some contend the tribe’s “depredations” warranted a violent response, but most seem to have held to the view that the initial provocation — the “theft” of a small number of cattle during a time of starvation — served as a pretext for wanton killing of indigenous people wherever they were to be found in the area. It is not a unique story. But it’s disappointing that such a credulous mid-19th century narrative made its way onto a marker placed at the end of the 20th century.